|

|

HUNGARIAN RHAPSODY Weeks 3-4 |

||

|

We were thankful for light Sunday morning traffic when we drove through Budapest to head out towards the Northern Uplands of Hungary and the Cserhát, Mátra and Bükk Hills.

Our route on a murky day took us over the Cserhát Hills, through fascinating villages with unpronounceable names like Galgagyörk, Pöspökhatvan or Balassagyarmat (try Bol-osh-sho dyor-mot). Our first stop was the village of Hollókő, promoted as a living centre of Palócs culture, a people of Slovak origins cut off by the border imposed by the Treaty of Trianon in 1920 which left ethnic groups isolated from their native lands. The old cottages on each side of the cobbled street were built of adobe brick with daubed and white-washed rendering. In the weaving house, we saw an elderly lady in traditional Palócs dress hand-weaving (Photo 1).

Our next major stop was the historical town of Gyöngyös (pronounced 'Dyurn-dyursh') set at the foot of the Mátra Hills. We camped some 12 kms north at a straightforward small site at Parád, and travelled into town on the Mátrafüred narrow gauge railway. Hungary has a superb national network of Tourist Information Centres called Tourinform and the one at Gyöngyös was particularly helpful. The Mátra Hills are one of Hungary's noted wine growing areas, and Gyöngyös' Bor Ház (Wine House), operated by the local Wine Producer's Association satisfied our needs for several days. The county's only mountain Kékes (pronounced Kay-kesh)(1014m), like all of Hungary's northern hills, is covered with beautiful beech and birch woods; the summit is sullied by a monstrous TV tower, but the views stretch southwards the Great Plain. Before moving on to Eger, we paused at Recsk. Older Hungarians will shudder at the very name: the quarries outside the village were the site of the notorious Death Camp operated by the AVO secret police in the early 1950s. Here 1000s of political prisoners were sentenced to forced labour in the quarries and were worked, starved or beaten to death. After Stalin's death in 1953, the camp was closed by Imre Nagy, who led the unsuccessful 1956 Uprising and was himself executed by the Communists. In 1991, the site was set up as a Nemzeti Emlékpark, a national memorial to those who died in such appalling conditions under this brutal regime, with remains of barbed wire, watchtower and primitive barrack hut. We shared the visit with a number of younger Hungarians who like us were clearly moved by this gruelling experience.

Our next stop was at Szilvásvárad (Sil-varsh-var-od), where Hungary's stock of Lippizaner white horses are bred for pulling show carriages. We stayed at the family run Hegyi Camping which for its setting and the welcome we received was awarded the accolade of campsite of the trip - visit their web site Hegyi Camping Szilvásvárad But we were less lucky with the Lippizaners: apart from a couple of superannuated stallions at the museum, there were no other horses to be seen. We continued our journey to the most northerly point of the trip, the limestone Karst country of the Aggtelek National Park, to stay at the expensive Baradla Camping just by the area's main cave of Baradla Barlang. The cave system stretches for some 25 kms, spanning the Hungarian/Slovak border; we enjoyed two ventures into the system to experience the most amazing formations (Photo 3). We paused on our journey to Miskolcs at the village of Rudabánya, whose name betrays its origins as the leading iron ore mining area of Hungary (ruda is an old Slavic word for ore). The mine expanded on a huge scale during the Communist period and closed in 1985, leaving the village impoverished of employment opportunities. Our reason for coming here was to visit the Ásvánbányászafi Múzeum tracing the history of iron extraction in Hungarian with an accompanying mineral collection. Andrea, the museum manager, showed us around and with assuring frankness answered our many questions about the Communist period and about social factors following the mine's closure. The museum contained an unprecedented collection of documents, artifacts, uniforms and mining memorabilia, and the highlight of the mineral collection was the fossilized partial skull of Ruda-pithecus Hungaricus, a 10 million year old primate found in the Rudabánya mine. The sadness is that, inspite of this impressive collection, Rudabánya is not on the main tourist route. But anyone visiting Hungary would miss a unique opportunity if they failed to visit the museum at Rudabánya. Andrea also arranged with the local pastor for us to visit the town's beautifully decorated Calvinist church.

But time is pressing. It's well into September and the evenings are getting dark and dewy. If we are to fulfill our plans to see other parts of Hungary, it's time to move on - to Tokaj, famous for its wines, the far east of the country bordering onto Ukraine, the valley of the river Tisza and the Great Plain. Coming soon .... Sheila and Paul Published: Monday 12 September 2005

|

We

camped that night near the former mining town of Salgótarján,

now clearly endowed with a wealth of modern industrial investment. 'To Strand' Camping was

another relic of the 1950s, but despite its run-down appearance and

antiquated facilities we were welcomed as if we were the first visitors since the

demise of Communism. More importantly, the fine weather returned and we

were able to explore the remains of Salgá

and Somoskó castles built on basalt outcrops to fortify these

remote areas along what is now the Slovak frontier. In fact Somoskó

is just inside Slovak

territory, but an arrangement now exists between Hungary and

Slovakia, both now EEC states, to cross the border in order to visit

the castle. Life seemed pretty basic in the isolated village of Salgóbánya

where water supply was still from pumps in the muddy street. While in Salgótarján,

we visited the Józef Bánya

Múzeum,

the town's last drift mine which closed in 1992; former

miners now show visitors around the workings some 50m underground. The decrepit

and wet state of the mine museum and corroded machinery conveyed a realistic

impression of the dangerous working conditions, with over 100 fatalities during the mine's 100 years working. As we left, we were wished Jó

Szerencsét ('Good Luck'), the miners' traditional greeting.

We

camped that night near the former mining town of Salgótarján,

now clearly endowed with a wealth of modern industrial investment. 'To Strand' Camping was

another relic of the 1950s, but despite its run-down appearance and

antiquated facilities we were welcomed as if we were the first visitors since the

demise of Communism. More importantly, the fine weather returned and we

were able to explore the remains of Salgá

and Somoskó castles built on basalt outcrops to fortify these

remote areas along what is now the Slovak frontier. In fact Somoskó

is just inside Slovak

territory, but an arrangement now exists between Hungary and

Slovakia, both now EEC states, to cross the border in order to visit

the castle. Life seemed pretty basic in the isolated village of Salgóbánya

where water supply was still from pumps in the muddy street. While in Salgótarján,

we visited the Józef Bánya

Múzeum,

the town's last drift mine which closed in 1992; former

miners now show visitors around the workings some 50m underground. The decrepit

and wet state of the mine museum and corroded machinery conveyed a realistic

impression of the dangerous working conditions, with over 100 fatalities during the mine's 100 years working. As we left, we were wished Jó

Szerencsét ('Good Luck'), the miners' traditional greeting.  Eger is

a delightful town, and the sign at the outskirts foretells its charms:

'City of vines and wine'. Approaching on minor roads, we encountered the dreaded road sign; when they say Úthibák,

they really do mean pot-holes. We camped at Tulipán Camping, ideally

located to walk into town. The central square is named after István Dobó,

leader of the 2,000 Magyar troops who in 1552 resisted the siege of Eger

by a 50,000 Turkish force. The redoubtable women of Eger are reputed to

have poured cauldrons of boiling goulash on the unfortunate Turks, a feat

celebrated by the monumental statues in the square (Photo 2). Eger is

home to the famous Hungarian wine Egri Bikavér (Bull's Blood); seeing the Magyars'

red wine-stained beards, the Turks

believed that their unyielding

courage came from drinking bull's blood. And the yarn is as good as the wine.

That evening we walked around to the Szépasszony Valley, to sample Egri Bikavér.

In one of the wine cellars, we enjoyed the company of Gábor

and Éva, who taught us the essential Hungarian word for 'cheers' - Egészségédre

(E-gays-shay-gay-dre) - we needed a long evening of drinking Bull's Blood in

order to perfect our pronunciation! It was a superb evening, and slow

start the following morning.

Eger is

a delightful town, and the sign at the outskirts foretells its charms:

'City of vines and wine'. Approaching on minor roads, we encountered the dreaded road sign; when they say Úthibák,

they really do mean pot-holes. We camped at Tulipán Camping, ideally

located to walk into town. The central square is named after István Dobó,

leader of the 2,000 Magyar troops who in 1552 resisted the siege of Eger

by a 50,000 Turkish force. The redoubtable women of Eger are reputed to

have poured cauldrons of boiling goulash on the unfortunate Turks, a feat

celebrated by the monumental statues in the square (Photo 2). Eger is

home to the famous Hungarian wine Egri Bikavér (Bull's Blood); seeing the Magyars'

red wine-stained beards, the Turks

believed that their unyielding

courage came from drinking bull's blood. And the yarn is as good as the wine.

That evening we walked around to the Szépasszony Valley, to sample Egri Bikavér.

In one of the wine cellars, we enjoyed the company of Gábor

and Éva, who taught us the essential Hungarian word for 'cheers' - Egészségédre

(E-gays-shay-gay-dre) - we needed a long evening of drinking Bull's Blood in

order to perfect our pronunciation! It was a superb evening, and slow

start the following morning.

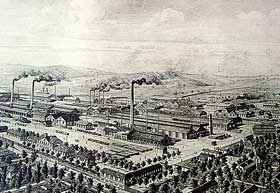

And so on to

Miskolc (pronounced Mish-kolts), Hungary's 3rd largest city and formerly a

major centre of iron and steel working. It still suffers from high levels

of unemployment and racial prejudice against the Roma

minority. Most of the heavy industry, which flourished in the Communist period, now lies in rusty ruins; contrast these

2 pictures of the city at the end of 19th century and contemporary Miskolc

with its ranks of tower blocks. Rather like Sheffield, Miskolc is now trying hard to

improve its image, and attracting industrial investment from western

companies such as Bosch. We camped outside the city up in the beautiful

beech-covered Bükk Hills at Lillafüred where iron smelting and forging

first began in the 18th century. The

And so on to

Miskolc (pronounced Mish-kolts), Hungary's 3rd largest city and formerly a

major centre of iron and steel working. It still suffers from high levels

of unemployment and racial prejudice against the Roma

minority. Most of the heavy industry, which flourished in the Communist period, now lies in rusty ruins; contrast these

2 pictures of the city at the end of 19th century and contemporary Miskolc

with its ranks of tower blocks. Rather like Sheffield, Miskolc is now trying hard to

improve its image, and attracting industrial investment from western

companies such as Bosch. We camped outside the city up in the beautiful

beech-covered Bükk Hills at Lillafüred where iron smelting and forging

first began in the 18th century. The