CAMPING IN DENMARK 2019 -

Jutland: CAMPING IN DENMARK 2019 -

Jutland:

Good to be on the Road again,

thanks to Autosleepers: as the Harwich overnight ferry for Hook of Holland drew away from the quay, we

took our customary seats by the ferry's lounge bow windows, savouring the moment

for the launch of our

belated 2019 trip to Denmark. This long-awaited moment brought to an end a

long, frustrating early summer of waiting for repairs to the raising roof of our

beloved VW camper, George, damaged back in April just before the start date for

our originally planned trip to Scandinavia. We therefore raised our glasses to

toast our thanks (see left) to Alan Curry, Customer Services Manager at Autosleepers

and his Service Engineer Paul Oliver. Autosleepers not only no

longer produce the solid-sided, raising-roof VW Trooper but regrettably also no

longer convert VW campers at all; components therefore for repair to

George's damaged roof were no longer available. Despite this however, these two

valued friends at Autosleepers managed, against all the odds and with supreme

ingenuity, skill and craftsmanship, to find the means of sourcing or fabricating the

necessary parts, achieving a remarkable repair to George's raising roof.

Our VW Trooper has been the whole basis for the

travelling

life style we have enjoyed during the many years of our retirement; its unique

solid-sided raising roof design has enabled us to camp in some extreme and

sub-zero weather conditions during our travels, and for that reason it is for us

irreplaceable. The excellent work carried out by Alan and Paul at Autosleepers

in carrying out such difficult repairs has therefore restored our ability to

continue our travels across Europe, and for that we are truly grateful to them.

Thank you. Good to be on the Road again,

thanks to Autosleepers: as the Harwich overnight ferry for Hook of Holland drew away from the quay, we

took our customary seats by the ferry's lounge bow windows, savouring the moment

for the launch of our

belated 2019 trip to Denmark. This long-awaited moment brought to an end a

long, frustrating early summer of waiting for repairs to the raising roof of our

beloved VW camper, George, damaged back in April just before the start date for

our originally planned trip to Scandinavia. We therefore raised our glasses to

toast our thanks (see left) to Alan Curry, Customer Services Manager at Autosleepers

and his Service Engineer Paul Oliver. Autosleepers not only no

longer produce the solid-sided, raising-roof VW Trooper but regrettably also no

longer convert VW campers at all; components therefore for repair to

George's damaged roof were no longer available. Despite this however, these two

valued friends at Autosleepers managed, against all the odds and with supreme

ingenuity, skill and craftsmanship, to find the means of sourcing or fabricating the

necessary parts, achieving a remarkable repair to George's raising roof.

Our VW Trooper has been the whole basis for the

travelling

life style we have enjoyed during the many years of our retirement; its unique

solid-sided raising roof design has enabled us to camp in some extreme and

sub-zero weather conditions during our travels, and for that reason it is for us

irreplaceable. The excellent work carried out by Alan and Paul at Autosleepers

in carrying out such difficult repairs has therefore restored our ability to

continue our travels across Europe, and for that we are truly grateful to them.

Thank you.

|

Click on 4 highlighted areas

for details of Jutland |

|

See

Campingplatz BUM near Borgdorf in

Schleswig-Holstein:

a long day's drive of 370 miles across Holland and Germany, with many autobahn hold-ups due to congested

traffic and road works, brought us with further delays past the landscape of

dockyard and container cranes at Hamburg, and under the Elbe Tunnel, for the final

100kms on the A7 into Schleswig-Holstein. 5kms around the lanes from A7 Junction

11 we finally reached See Campingplatz

BUM near Borgdorf. Since our last stay here in 2017, the lake-side camping See

Campingplatz BUM near Borgdorf in

Schleswig-Holstein:

a long day's drive of 370 miles across Holland and Germany, with many autobahn hold-ups due to congested

traffic and road works, brought us with further delays past the landscape of

dockyard and container cranes at Hamburg, and under the Elbe Tunnel, for the final

100kms on the A7 into Schleswig-Holstein. 5kms around the lanes from A7 Junction

11 we finally reached See Campingplatz

BUM near Borgdorf. Since our last stay here in 2017, the lake-side camping area

had been further enlarged and terraced with additional power supplies. Weary

after today's long drive, we sat in the late afternoon sunshine, enjoying

crisply fresh German beers (see left) (Photo

1 - See Campingplatz BUM), revelling in being able once more to

enjoy George's companionship. We woke to a bright morning and

breakfasted outside at the lake's edge in lovely warm sunshine to enjoy a

relaxed morning in camp (see right). The family that kept See Campingplatz BUM

were friendly and hospitably welcoming, and the charge was a very reasonable

€18.50. It was an altogether good site rated by as +5, so convenient to the

autobahn as a staging camp on the way up to Jutland. area

had been further enlarged and terraced with additional power supplies. Weary

after today's long drive, we sat in the late afternoon sunshine, enjoying

crisply fresh German beers (see left) (Photo

1 - See Campingplatz BUM), revelling in being able once more to

enjoy George's companionship. We woke to a bright morning and

breakfasted outside at the lake's edge in lovely warm sunshine to enjoy a

relaxed morning in camp (see right). The family that kept See Campingplatz BUM

were friendly and hospitably welcoming, and the charge was a very reasonable

€18.50. It was an altogether good site rated by as +5, so convenient to the

autobahn as a staging camp on the way up to Jutland.

Crossing into Denmark near Tønder in SW

Jutland:

re-joining A7 northwards, we shortly crossed over the impressively wide Kiel

Canal which cuts through the Schleswig-Holstein peninsula connecting the North

sea and Baltic Sea. At the northernmost German city of Flensburg, we turned off

the motorway and followed back lanes to cross into Denmark on the south-western

side of Jutland (click

here for detailed map of route). Observing the relaxed Danish speed

limit of 80kph (50mph) for trunk roads, we drove into the nearby town of Tønder

to shop for provisions, getting our first experience of the Danish high cost of

living.

The Wadden Sea and Vidå Sluice at the

Forward Coastal Dyke: from Tønder,

country lanes

through flat coastal farming countryside led to the village of Højer, where we

continued out towards the Wadden Sea coast across polders (reclaimed former

marshland) and the Højer Dyke, following

the Vidå River to where it now enters the Wadden Sea through the Vidå

Sluice at the massively impressive Forward

Coastal Dyke. The Wadden Sea and Vidå Sluice at the

Forward Coastal Dyke: from Tønder,

country lanes

through flat coastal farming countryside led to the village of Højer, where we

continued out towards the Wadden Sea coast across polders (reclaimed former

marshland) and the Højer Dyke, following

the Vidå River to where it now enters the Wadden Sea through the Vidå

Sluice at the massively impressive Forward

Coastal Dyke.

The Wadden Sea, stretching around the coasts of

Holland, North Germany and SW Jutland, is extremely tidal, with a tidal

difference of up to 2m between high and low tides every 25 hours. The reclaimed

polders of the fertile Tønder coastal marshlands had always been settled and

cultivated, but farms and buildings had to be raised on mounds and land

protected by dykes, from the constant hazard of flooding by sea-water during

storm tides, and by river water during winter~spring high flow periods. In 1861

the Højer Dyke was built protecting the then line of the Wadden Sea coast and

the outflow of the Vidå River controlled by Højer Sluice. With more intensive

exploitation and settlement of the Tønder reclaimed marshlands during the 20th

century, the threat of flooding of the coastal area, most of which lies at sea

level, became more critical. A severe storm tide in January 1976, which

threatened to overspill the existing coastal Højer Dyke, led to a Danish

parliamentary decision to construct a new 8m high forward coastal dyke to

protect settlements and agricultural land in the Tønder area. The Forward

Coastal Dyke was constructed between 1979~81, 1.4kms west and seaward of, and

parallel with, the old Højer Dyke, creating an extended new coastline. The Vidå

is the third largest river in Denmark, The Wadden Sea, stretching around the coasts of

Holland, North Germany and SW Jutland, is extremely tidal, with a tidal

difference of up to 2m between high and low tides every 25 hours. The reclaimed

polders of the fertile Tønder coastal marshlands had always been settled and

cultivated, but farms and buildings had to be raised on mounds and land

protected by dykes, from the constant hazard of flooding by sea-water during

storm tides, and by river water during winter~spring high flow periods. In 1861

the Højer Dyke was built protecting the then line of the Wadden Sea coast and

the outflow of the Vidå River controlled by Højer Sluice. With more intensive

exploitation and settlement of the Tønder reclaimed marshlands during the 20th

century, the threat of flooding of the coastal area, most of which lies at sea

level, became more critical. A severe storm tide in January 1976, which

threatened to overspill the existing coastal Højer Dyke, led to a Danish

parliamentary decision to construct a new 8m high forward coastal dyke to

protect settlements and agricultural land in the Tønder area. The Forward

Coastal Dyke was constructed between 1979~81, 1.4kms west and seaward of, and

parallel with, the old Højer Dyke, creating an extended new coastline. The Vidå

is the third largest river in Denmark,

draining a 1,400km2 catchment

with its source on a glacial ridge near Aabenraa in SE Jutland. During the 19th

century, the river regularly flooded the low-lying Tønder marshlands during winter high

flow periods, leaving dry only dykes and buildings on mounds. During the 1920s,

the lower Vidå was canalised with protective embankments and water pumped from

marshes into the river. Prior to construction of the Forward Coastal Dyke in

1981, the Vidå River flowed into the Wadden Sea through Højer Sluice. It is now

controlled at its extended outflow at Vidå Sluice in the Forward Coastal Dyke.

The sluice consists of 3 chambers with a total width of 20m. Facing the sea on

the outward side are 3 pairs of automatic sluice gates, with 3 pairs of storm

shields on the inland side of the sluice facing up-river. Water levels are

monitored on both marine and inland sides, in order to forecast storm tide

warnings. During prolonged high tides in the Wadden Sea, the draining a 1,400km2 catchment

with its source on a glacial ridge near Aabenraa in SE Jutland. During the 19th

century, the river regularly flooded the low-lying Tønder marshlands during winter high

flow periods, leaving dry only dykes and buildings on mounds. During the 1920s,

the lower Vidå was canalised with protective embankments and water pumped from

marshes into the river. Prior to construction of the Forward Coastal Dyke in

1981, the Vidå River flowed into the Wadden Sea through Højer Sluice. It is now

controlled at its extended outflow at Vidå Sluice in the Forward Coastal Dyke.

The sluice consists of 3 chambers with a total width of 20m. Facing the sea on

the outward side are 3 pairs of automatic sluice gates, with 3 pairs of storm

shields on the inland side of the sluice facing up-river. Water levels are

monitored on both marine and inland sides, in order to forecast storm tide

warnings. During prolonged high tides in the Wadden Sea, the sluice gates are

kept shut. Accumulating water in the Vidå River then overflows into the

Margrethe Kog polder and reservoir on the inner side of the Forward Coastal

Dyke. On the outer seaward side of the Forward Coastal Dyke, a number of

sedimentation pans were created to promote the formation of new fore-shore and

enhance dyke safety. sluice gates are

kept shut. Accumulating water in the Vidå River then overflows into the

Margrethe Kog polder and reservoir on the inner side of the Forward Coastal

Dyke. On the outer seaward side of the Forward Coastal Dyke, a number of

sedimentation pans were created to promote the formation of new fore-shore and

enhance dyke safety.

We followed the lane out from Højer village

across the polders grazing lands towards the old Højer Dyke. The road rose and

dog-legged over the dyke towards Højer Sluice which formerly controlled the

River Vidå's outflow into the Wadden Sea (see above left). The lane continued alongside

the now

canalised lower course of the Vidå for 2kms,and in the distance we could see the

control tower of the 1982 Vidå Sluice. Towards the end of the lower Vidå, the

river forked into the area of reservoir into which the river now overspills when

prolonged high tides make necessary the sluice gates' closure. Extending

leftwards beyond the river's lower course, the Margrethe Kog polder stood

landward of the line of the new Forward Coastal Dyke and the saltwater lake. At

lane's end, we parked by the small restaurant and Vidå exhibition house, and

walked over to explore the sluice, climbing up onto the apex of the Forward

Coastal Dyke which stretched away into the distance north and south along the

new outer coastline. From here we could look inland up the lower length of the

river and across the Margrethe Kog polder and overflow reservoir to its right

(see above right).

We were surprised at the shallow angle of the dyke's outer seaward face which

sloped gently down to the shore-line and the fore-shore sedimentation pans (see

above left).

Older dykes were built with more upright faces on both sides, which were

battered by the full force of tides on the outer seaward face. Modern dykes

such as the Forward Coastal Dyke are now constructed with more gently sloping

outer face towards the sea; this forces storm surge waves to release their energy

slowly instead of hitting the dyke wall with full force. Many of the older dykes

have now been modified with more gently sloping outer faces. walked over to explore the sluice, climbing up onto the apex of the Forward

Coastal Dyke which stretched away into the distance north and south along the

new outer coastline. From here we could look inland up the lower length of the

river and across the Margrethe Kog polder and overflow reservoir to its right

(see above right).

We were surprised at the shallow angle of the dyke's outer seaward face which

sloped gently down to the shore-line and the fore-shore sedimentation pans (see

above left).

Older dykes were built with more upright faces on both sides, which were

battered by the full force of tides on the outer seaward face. Modern dykes

such as the Forward Coastal Dyke are now constructed with more gently sloping

outer face towards the sea; this forces storm surge waves to release their energy

slowly instead of hitting the dyke wall with full force. Many of the older dykes

have now been modified with more gently sloping outer faces.

From the sluice control tower at the dyke apex,

we walked down the gently sloping outer face to stand above the sluice's seaward

storm gates (see above right), beyond which the Vidå River flowed out into the Wadden Sea. We

walked down alongside the outflow over the mudflats for photos looking back

towards the sluice and gently sloping dyke

(see left) (Photo 2 - Outflow of Vidå River into Wadden Sea). Back over the high dyke, we found

the Vidå exhibition which gave more information on Wadden Sea tides, storm

surges when powerful westerly gales force water several metres over its normal

level inland into the river's mouth, and bird- and wild-life of the Wadden Sea

coast.

Rudbøl Camping on the line of the

Danish~German border:

by now its was 5-00pm and we drove back around the lanes to Højer village turning south on a lane which ran along the crest of the Gammel Højer Dige (Old

Højer Dyke) alongside the Vidå River which meandered through the reclaimed

polders farmland where sheep and cattle grazed. In 3kms we reached Rudbøl village,

and in the heart of the village found tonight's campsite, Rudbøl

Camping. We were greeted in friendly and welcoming manner by the lady owner who

showed us round; the charge of 210kr seemed high for a modest campsite, but this

was markedly cheaper than most of the larger and over-luxurious Danish

holiday-camps which we should try to avoid. The site was large with many statics in the central area

unoccupied mid-week, but with plenty of spaces further over. Having

filled

George's fresh water, we settled into a deserted open area where we had total

privacy and access to power, and relaxed with beers in the evening sunshine

(see right) (Photo 3 - Rudbøl Camping). The

sun set behind a line of poplars and the evening grew cool. Today had been a

shorter and more relaxing day, but we had learned much about life on the Wadden

Sea coast of SW Jutland and the measures taken to protect against storm tides.

And tonight we were camped at what must be Jutland's southernmost village,

exactly on the line of the Danish~German border formed by the Vidå River, drawn

in 1920 with the post-WW1 partition of South Jutland and Schleswig-Holstein. filled

George's fresh water, we settled into a deserted open area where we had total

privacy and access to power, and relaxed with beers in the evening sunshine

(see right) (Photo 3 - Rudbøl Camping). The

sun set behind a line of poplars and the evening grew cool. Today had been a

shorter and more relaxing day, but we had learned much about life on the Wadden

Sea coast of SW Jutland and the measures taken to protect against storm tides.

And tonight we were camped at what must be Jutland's southernmost village,

exactly on the line of the Danish~German border formed by the Vidå River, drawn

in 1920 with the post-WW1 partition of South Jutland and Schleswig-Holstein.

The Danish~German border:

after much rain in the night, which successfully tested George's newly repaired

roof, we woke to a much cooler weather and heavily overcast sky and spent a

relaxed morning sitting out the frequent heavy showers. Before leaving Rudbøl,

we drove through the village to the line of the Danish~German open border and

crossed the Vidå bridge at the point where the river swells out into another

flood lake. Having crossing the border into the neighbouring German village of

Rosenkranz simply for the sake of it, we turned back into Denmark by a surviving

border barrier and sat at a lake-side picnic table for our lunch sandwiches by

the combined flags of the Nordic countries which proudly signified the border

(see left)

(Photo 4 - Danish~German border). The Danish~German border:

after much rain in the night, which successfully tested George's newly repaired

roof, we woke to a much cooler weather and heavily overcast sky and spent a

relaxed morning sitting out the frequent heavy showers. Before leaving Rudbøl,

we drove through the village to the line of the Danish~German open border and

crossed the Vidå bridge at the point where the river swells out into another

flood lake. Having crossing the border into the neighbouring German village of

Rosenkranz simply for the sake of it, we turned back into Denmark by a surviving

border barrier and sat at a lake-side picnic table for our lunch sandwiches by

the combined flags of the Nordic countries which proudly signified the border

(see left)

(Photo 4 - Danish~German border).

Crossing the tidal causeway to the Wadden Sea island of Mandø:

we returned along the crest of the old Højer Dyke across agricultural polders

countryside riddled with drainage channels, and through Højer village we

continued north on Route 419 following the Wadden Sea coastline with the German

holiday island of Sylt and Danish island of Rømø lining the western horizon (click

here for detailed map of route). With the sun bright, a brisk westerly

wind from off the Wadden Sea created an impressive cloudscape. Into Skærbæk, we

shopped for 2 nights' provisions for our time on the offshore Wadden Sea island

of Mandø, which is connected to the Danish mainland by a 6kms long low gravel

causeway and only accessible twice daily at low tide. Continuing north on the

main Route 11, we turned off to the twee, des-res village of Vester Vedstad, and

the UNESCO World Heritage Wadden Sea Centre. We had earlier tried twice to

telephone to confirm our tide tables information for safe early evening

low tide crossing times to Mandø, but inevitably got no reply. From our past

experience of such Crossing the tidal causeway to the Wadden Sea island of Mandø:

we returned along the crest of the old Højer Dyke across agricultural polders

countryside riddled with drainage channels, and through Højer village we

continued north on Route 419 following the Wadden Sea coastline with the German

holiday island of Sylt and Danish island of Rømø lining the western horizon (click

here for detailed map of route). With the sun bright, a brisk westerly

wind from off the Wadden Sea created an impressive cloudscape. Into Skærbæk, we

shopped for 2 nights' provisions for our time on the offshore Wadden Sea island

of Mandø, which is connected to the Danish mainland by a 6kms long low gravel

causeway and only accessible twice daily at low tide. Continuing north on the

main Route 11, we turned off to the twee, des-res village of Vester Vedstad, and

the UNESCO World Heritage Wadden Sea Centre. We had earlier tried twice to

telephone to confirm our tide tables information for safe early evening

low tide crossing times to Mandø, but inevitably got no reply. From our past

experience of such places, UNESCO status is symbolic of the ultimate in negative attributes: high

on pretentious glitziness and entry cost, low on value as a source of

substantive detailed information, and the Wadden Sea Centre was no exception!

With zero expectations, we enquired with the girl at reception about earliest

safe crossing times to Mandø this evening with low tide presently set at 8-20pm.

As expected, she was utterly unhelpful and evasive - no tide

tables, no information, no help, nothing to justify the place's costly and

pretentious status! Instead we phoned the shop-cum-campsite on Mandø and were

assured that we could cross safely up to 2 hours before and after low tide time.

places, UNESCO status is symbolic of the ultimate in negative attributes: high

on pretentious glitziness and entry cost, low on value as a source of

substantive detailed information, and the Wadden Sea Centre was no exception!

With zero expectations, we enquired with the girl at reception about earliest

safe crossing times to Mandø this evening with low tide presently set at 8-20pm.

As expected, she was utterly unhelpful and evasive - no tide

tables, no information, no help, nothing to justify the place's costly and

pretentious status! Instead we phoned the shop-cum-campsite on Mandø and were

assured that we could cross safely up to 2 hours before and after low tide time.

All the tractor-buses, which at great expense

convey tourists across the mud flats for day trips to Mandø, returned, and at

6-00pm we set off around the lane to the coastal dyke to begin the crossing of

Mandø causeway, the Låningsvej (see right). The brisk westerly wind kept the showers at bay,

and driving into a magnificently dramatic Big Sky cloudscape (see above left

and right) (Photo

5 - Crossing Mandø causeway),

we crossed the

6kms of wet, muddy gravel causeway. 5kms over, the lane became tarmac again,

rising over the higher, grass-covered salt-marshes to reach Mandø island and its

farming village. Here we located the small campsite and settled into a quiet

corner, looking out across the pastureland towards the island's eastern side (Photo

6 - Mandø Camping). we crossed the

6kms of wet, muddy gravel causeway. 5kms over, the lane became tarmac again,

rising over the higher, grass-covered salt-marshes to reach Mandø island and its

farming village. Here we located the small campsite and settled into a quiet

corner, looking out across the pastureland towards the island's eastern side (Photo

6 - Mandø Camping).

Mandø island: Mandø is one of the

northernmost of the line of glacially deposited islands, sandbanks and mud-flats

lying along the length of the North Friesian coastline stretching from Holland,

North Germany to SW Jutland, which separate the shallow Wadden Sea from the

North Sea beyond the continental shelf. This chain of islands forms the remains

of a pre-Ice Age coastline before sea levels rose creating the Wadden Sea. Mandø

covers an area of just over 7 square kms. Extensive mud-flats and tidal marshes

surround the island, providing breeding grounds for multitudes of sea birds and

Common and Grey Seals. There are currently 60 permanent residents on Mandø and

the islanders have traditionally made a living from fishing and farming;

nowadays tourism provides a secondary source of earnings. An earth dyke was

constructed around the island's perimeter set back from the shore-line, to

protect the cultivable land from storm tides for cereal crops and for sheep and

cattle grazing. North Friesian coastline stretching from Holland,

North Germany to SW Jutland, which separate the shallow Wadden Sea from the

North Sea beyond the continental shelf. This chain of islands forms the remains

of a pre-Ice Age coastline before sea levels rose creating the Wadden Sea. Mandø

covers an area of just over 7 square kms. Extensive mud-flats and tidal marshes

surround the island, providing breeding grounds for multitudes of sea birds and

Common and Grey Seals. There are currently 60 permanent residents on Mandø and

the islanders have traditionally made a living from fishing and farming;

nowadays tourism provides a secondary source of earnings. An earth dyke was

constructed around the island's perimeter set back from the shore-line, to

protect the cultivable land from storm tides for cereal crops and for sheep and

cattle grazing.

An afternoon's walking around Mandø's

western coastline: we woke to a bright sunny morning and breakfast outside (Photo

7 - Breakfast at Mandø Camping) (see right), spending a relaxing and peaceful morning in camp enjoying the

sunshine and solitude. We packed a day sac and set off for an afternoon of

walking around Mandø's western coastline. Just around the corner from the

campsite by the village's central 'square', where the tractor buses deposited today's bevies of tourists, we found the little Brugsen shop and settled up our

2 day's campsite rent, thanking the lady for her help with An afternoon's walking around Mandø's

western coastline: we woke to a bright sunny morning and breakfast outside (Photo

7 - Breakfast at Mandø Camping) (see right), spending a relaxing and peaceful morning in camp enjoying the

sunshine and solitude. We packed a day sac and set off for an afternoon of

walking around Mandø's western coastline. Just around the corner from the

campsite by the village's central 'square', where the tractor buses deposited today's bevies of tourists, we found the little Brugsen shop and settled up our

2 day's campsite rent, thanking the lady for her help with causeway low tide

crossing times. Strandvej led out over the western line of dunes and down to the

island's western shoreline where the Stormflodssøjlen column indicated record

heights of storm flood tides over the years since the disastrous tide of 1691. causeway low tide

crossing times. Strandvej led out over the western line of dunes and down to the

island's western shoreline where the Stormflodssøjlen column indicated record

heights of storm flood tides over the years since the disastrous tide of 1691.

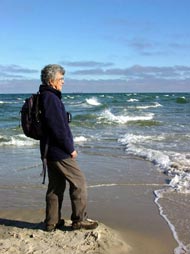

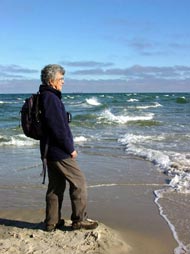

With a crisp westerly wind blowing and bright

afternoon sun sparkling on the Wadden Sea across the sandbanks, we walked down

to the water's edge for photographs along the shoreline (see left) (Photo

8 - Mandø's western shoreline). A track around the western foreshore led

just below the line of dunes, northwards parallel with the coast. Here massed

thickets of wild roses (Rosa rugosa) (see right) (Photo

9 - Wild Roses - Rosa rugosa), so characteristic of Denmark,

blossomed along the foreshore, covered with huge rose-hips and their dusky pink

and white flowers mostly over but still enough of them to fill the air with

their familiar scent. We ambled along the beautiful foreshore pausing

frequently to photograph the flora, which included

Toadflax

(see below left), Yellow Rattle, Slender Centuary, and Restharrow. The path curved around under the line of dunes,

gaining a little height to join the roadway that ran around in the lee of the

NW section of the massive dyke which encircles the island, protecting the

village and farmland from tidal storm floods. This entire centrally enclosed

area of the island is criss-crossed by a cleverly constructed network of

drainage dikes which all feed into a main dike running transversely E~W across

the island's centre to outflow through a sluice on the east coast. Toadflax

(see below left), Yellow Rattle, Slender Centuary, and Restharrow. The path curved around under the line of dunes,

gaining a little height to join the roadway that ran around in the lee of the

NW section of the massive dyke which encircles the island, protecting the

village and farmland from tidal storm floods. This entire centrally enclosed

area of the island is criss-crossed by a cleverly constructed network of

drainage dikes which all feed into a main dike running transversely E~W across

the island's centre to outflow through a sluice on the east coast.

Once we had passed from the open west-facing

foreshore out of the wind into the lee of the huge dyke, the afternoon sun felt

warm. We followed the roadway northwards past a long, linear flood reservoir

either side of the island's central drainage dike. Grazing sheep stared down on

us from the crest of the dyke. The roadway curved round past ponds where many

birds gathered to reach the island's northern point. Here a side-track ran down

from the dyke towards the northern shore-line at Skelbankerampe. At the water's

edge we could look out over sand flats where at low tide colonies of seals bask

and oyster beds form on the mud banks (see right). Back up to the dyke, we returned through

sheep pastures on the more gently sloping outer seaward face, and along the

dykes crest high above the roadway. Dropping down the dyke's steep inner face,

we returned along Klitvej to the village, as the last of today's tourists were

departing in the tractor-bus. Today's 7kms walk had been thoroughly rewarding,

giving us a fuller understanding of Mandø's topography and the flood protection

and drainage that over time had made farming life on the island possible.

A change of weather for our return to the

mainland: more cloud gathered late evening foreshadowing the change of wind direction to south which

would bring tomorrow's forecast rain. The following morning duly brought heavily

overcast sky and cooler, wind-driven persistent drizzle; it was going to be a

thoroughly unpleasant day for our return to the mainland. We had been very

fortunate in having such a fine day and clear light for yesterday's shore-line

walk. We needed to be away by 10-30am latest for a safe crossing of the causeway

with low tide being at 9-30. From Mandø By (village) we headed across the

farmland to cross the northern peripheral dyke and began the return crossing of

the gravel causeway, passing a tractor-bus ferrying out the first of today's

tourists for a wretchedly wet day on Mandø.

Tipperne Bird Reserve at Ringkøbing Fjord:

back across at the mainland, we headed north on Rte 11 with the attractive view

of Ribe's ancient medieval church towering over this former Viking port-town (click

here for detailed map of route). Rte 11 crossed the Esbjerg~Kolding

motorway and continued north to Varde where we re-stocked with provisions at a

Kvickly supermarket in the centre of town. As we turned off onto Rte 181 through

Nørre Nebel, the sky darkened dramatically and the forecast pouring rain began.

Our plan this afternoon had been to explore the bird-watching potential of the

Tipperne Peninsula Bird Reserve which extended into the southern part of Ringkøbing Fjord,

but in this driving rain and poor visibility, the chances of seeing much seemed

limited. We had been told that the gate into the Tipperne limited access

conservation reserve was only open from 9-30am to 3-30pm; despite the adverse

weather, we had an hour today for an exploratory foray. The lane leading to the

Tipperne conservation area gate soon became unsurfaced, and driving along the

2kms of gravelled approach lane, we disturbed a number of birds from the

surrounding moorland long grass: Snipe (recognised from having seen so many 2

years ago in Iceland), Grey Heron and Curlew. In pouring rain and poor light we

reached lane's end at the bird observation tower, but in such weather it simply was not worth a

purposeless soaking attempting to climb the tower today; we should have to return in the

morning in better weather. Tipperne Bird Reserve at Ringkøbing Fjord:

back across at the mainland, we headed north on Rte 11 with the attractive view

of Ribe's ancient medieval church towering over this former Viking port-town (click

here for detailed map of route). Rte 11 crossed the Esbjerg~Kolding

motorway and continued north to Varde where we re-stocked with provisions at a

Kvickly supermarket in the centre of town. As we turned off onto Rte 181 through

Nørre Nebel, the sky darkened dramatically and the forecast pouring rain began.

Our plan this afternoon had been to explore the bird-watching potential of the

Tipperne Peninsula Bird Reserve which extended into the southern part of Ringkøbing Fjord,

but in this driving rain and poor visibility, the chances of seeing much seemed

limited. We had been told that the gate into the Tipperne limited access

conservation reserve was only open from 9-30am to 3-30pm; despite the adverse

weather, we had an hour today for an exploratory foray. The lane leading to the

Tipperne conservation area gate soon became unsurfaced, and driving along the

2kms of gravelled approach lane, we disturbed a number of birds from the

surrounding moorland long grass: Snipe (recognised from having seen so many 2

years ago in Iceland), Grey Heron and Curlew. In pouring rain and poor light we

reached lane's end at the bird observation tower, but in such weather it simply was not worth a

purposeless soaking attempting to climb the tower today; we should have to return in the

morning in better weather.

Bork Havn

Camping on southern shore of Ringkøbing Fjord: back

along the lanes, we turned off to find tonight's planned campsite, Bork Havn

Camping on the southern shore of Ringkøbing Fjord, which we had first used in 2007

and again on our return from Norway in September 2014. As always, the

long-standing owners greeted us with a warm and friendly welcome. The site

was well priced at 195kr (plus extra for showers) with clean, modern facilities

and well-equipped kitchen, and was divided by hedges into a number of bays mostly now

filled by statics. In peak summer time, Bork Havn

would be insufferably noisy,

but most of the statics were empty at this late stage in the year; even so the

noise of TVs in caravan awnings was an irritating intrusion. would be insufferably noisy,

but most of the statics were empty at this late stage in the year; even so the

noise of TVs in caravan awnings was an irritating intrusion.

A day of bird-watching around Ringkøbing Fjord:

the sky was clearing with a bright sun when we departed the following morning

for our day of bird-watching around Ringkøbing Fjord (click

here for detailed map of route). We returned firstly to Tipperne, and at the peninsula tip, climbed the bird observation tower to scan

the fjord and reed beds through binoculars (see above right). On a sunny day, there was less

bird-life in the approach meadows than in yesterday's rain, but Oyster Catchers

were feeding on the shore-side turf and in the distance a flock of geese could

be seen, with swans on the fjord. Swallows flitted around the Tipperne Reserve

building, nesting under the thatched eaves. Before leaving Tipperne, we diverted

down to another observation tower overlooking the Fugletårn. This was a

wonderfully peaceful place, and an ideal secluded spot for a wild camp. From the

tower overlooking the lake shallows and reed-beds, we recorded seeing a Grey

Heron, several Greenshanks, a Curlew, and two unidentified birds of prey soaring

over the meadows where reeds cut for thatching had been stacked. the

tower overlooking the lake shallows and reed-beds, we recorded seeing a Grey

Heron, several Greenshanks, a Curlew, and two unidentified birds of prey soaring

over the meadows where reeds cut for thatching had been stacked.

We drove around to Lønborg from where a road

ran north, crossing the Skjern Å (River) which here at its outflow into Ringkøbing Fjord

spreads into many channels and lagoons. We pulled into a parking area where a

raised hide looked over one of the lagoons and reed-beds. Many Mute Swans glided

around the lagoon with their wing feathers raised, flocks of Lapwings flew over

or stood on the turf banks in their characteristic manner all facing the same

direction. Through binoculars, their head-crests were clearly visible. In

amongst the Lapwings were a few Golden Plovers, a Yellowhammer pecked on the

ground just below the hide, and a Heron stood among the reeds. Again Swallows

flitted around the hide, even swooping inside through open windows and perching

on rafters where a nest still contained young birds. We crossed the bridges

towards Skjern and turned off around lanes to Pumping Station Nord which had

once pumped water from the then drained

meadows into the Skjern Å. The roof-top

viewing platform gave views over the meadows and river, but there was no

bird-life to be seen here. meadows into the Skjern Å. The roof-top

viewing platform gave views over the meadows and river, but there was no

bird-life to be seen here.

We followed the fjord-side road

northwards, passing though attractive villages around to Ringkøbing at the head

of the fjord. Bypassing the town, we continued north and turned off beyond Vest

Stadil Fjord to find hides shown on a map-leaflet we had from our 2007 Danish

trip. From a parking area, a path led across the meadows to a hide overlooking

another small lake. A pair of Marsh Harriers soared over the meadows, and from

the hide we could see a number of Cormorants standing on islets in the

lake, and Terns flitting over and dipping in the lake. To the distant

westwards, the line of coastal dunes were visible along the West Jutland coast whose deposition over time had trapped the enclosed inland lagoons which now

form Ringkøbing and Nissum Fjords. Out to the main Route 181 coast road behind

these dunes at Husby Klit, we clambered up over the dunes where sweetly scented wild roses

flourished, and down to the deserted West Jutland beaches which stretched away

mile after mile north and south backed by the line of dunes (see above

left). The light was

perfect for photographs from high on the dunes (Photo

10 - Husby Klit dunes) and down by the water's edge,

where wind driven surf crashed onto the shore (see above right). lagoons which now

form Ringkøbing and Nissum Fjords. Out to the main Route 181 coast road behind

these dunes at Husby Klit, we clambered up over the dunes where sweetly scented wild roses

flourished, and down to the deserted West Jutland beaches which stretched away

mile after mile north and south backed by the line of dunes (see above

left). The light was

perfect for photographs from high on the dunes (Photo

10 - Husby Klit dunes) and down by the water's edge,

where wind driven surf crashed onto the shore (see above right).

Ringkøbing Camping:

back south on Rte 181 passing farms whose cattle grazed the fjord meadows, we turned off

at Søndervig to Ringkøbing to shop for provisions at the Brugsen

supermarket, and 2kms east beyond the town in woodland, we reached Ringkøbing

Camping. It was a large site with a range of pitches scattered among the

woodlands, and not unduly crowded. After a long day, we quickly settled in and

the barbecue was lit for supper in spite of threatening rain (see above left). In fact it poured all

night, and was still raining the following morning, giving George's new roof a

thorough testing. The campsite facilities were good, with two blocks of modern,

clean WC/showers and kitchenette/wash-ups. By the time we were ready to leave,

the sky was at last beginning to clear and sun breaking through (see right).

Thyborøn ferry across mouth of Limfjord to Agger: we headed north

on Route 181 (click

here for detailed map of route) following the line of the West Jutland

coast, along the sandbar

whose narrow strip of high dunes stretching for miles down the coast separates

the North Sea from the inland Thyborøn ferry across mouth of Limfjord to Agger: we headed north

on Route 181 (click

here for detailed map of route) following the line of the West Jutland

coast, along the sandbar

whose narrow strip of high dunes stretching for miles down the coast separates

the North Sea from the inland Nissum Fjord.

The road passed through Thorsminde village

and its harbour which have developed around the sluice which

now controls the Nissum Fjord's outflow. With time now pressing, and just an hour to reach Thyborøn in

time for the 3-00pm ferry across to Agger on the far side of the Limfjord

outflow, we drove at pace for the remaining section of peninsula up to Thyborøn.

We reached the ferry dock with just 10 minutes to spare, and joined other

vehicles waiting to board for the 10 minute crossing (see left); the brisk

westerly wind raised white horses in the choppy waters of the mouth of Limfjord.

Ashore on the far bank, we drove north up the length of the desolate Agger Tange

sand spit, and turned west by Agger village's little harbour on Nissum

Bredning. At Vestervig church, Route 527 led north towards Thisted to reach Route 26

at Sundby; we turned SW-wards, crossing the huge girder bridge over Vilsund

Sound onto the large island of Mors (Photo

11 - Vilsund Sound bridge) (see right). Route 26 was a confusing road, busy with

traffic, and alternating stretches of 90kph highway with sudden poorly indicated

shorter stretches of 80kph speed limit, and one of only two speed cameras we

encountered in the whole of Denmark. Nissum Fjord.

The road passed through Thorsminde village

and its harbour which have developed around the sluice which

now controls the Nissum Fjord's outflow. With time now pressing, and just an hour to reach Thyborøn in

time for the 3-00pm ferry across to Agger on the far side of the Limfjord

outflow, we drove at pace for the remaining section of peninsula up to Thyborøn.

We reached the ferry dock with just 10 minutes to spare, and joined other

vehicles waiting to board for the 10 minute crossing (see left); the brisk

westerly wind raised white horses in the choppy waters of the mouth of Limfjord.

Ashore on the far bank, we drove north up the length of the desolate Agger Tange

sand spit, and turned west by Agger village's little harbour on Nissum

Bredning. At Vestervig church, Route 527 led north towards Thisted to reach Route 26

at Sundby; we turned SW-wards, crossing the huge girder bridge over Vilsund

Sound onto the large island of Mors (Photo

11 - Vilsund Sound bridge) (see right). Route 26 was a confusing road, busy with

traffic, and alternating stretches of 90kph highway with sudden poorly indicated

shorter stretches of 80kph speed limit, and one of only two speed cameras we

encountered in the whole of Denmark.

Island of Fur in Limfjord:

the entire span of Jutland's northern region is in fact an island separated by Limfjord, a body of water

which stretches from the west coast at Agger to the east coast beyond Aalborg. Across the width of Mors, a wider bridge

spanned the Salting Sound, with Island of Fur in Limfjord:

the entire span of Jutland's northern region is in fact an island separated by Limfjord, a body of water

which stretches from the west coast at Agger to the east coast beyond Aalborg. Across the width of Mors, a wider bridge

spanned the Salting Sound, with Limfjord's ubiquitously pervasive spread

stretching away to the north like an inland sea (click

here for detailed map of route). Back onto the NW Jutland

'mainland', we turned off across the Selling peninsula, winding a way on back

lanes to reach the dock at Brandon for the 5 minute ferry crossing over the

narrow channel to the Limfjord island of Fur

(Photo

12 - Fur Island ferry) (see left). We wound a way around the island's

lanes over to the north coast, ending at Fur Camping. The grassy camping areas were tiered up the

steep hill-side, but we managed

to find a pitch that was not unduly sloping or vulnerable to noise from

holiday-making Danes in the many statics. The place had changed drastically from

the straightforward and untamed wooded campsite recalled from our 2007 visit to

Fur; it was then called Råkilde Camping, with a charactersome back-woodsman

owner. In contrast however, it was now very much a Danish holiday-camp, extended in terraces up the

hillside, with a different atmosphere, different clientele, and very different

owners as we were shortly to discover. Limfjord's ubiquitously pervasive spread

stretching away to the north like an inland sea (click

here for detailed map of route). Back onto the NW Jutland

'mainland', we turned off across the Selling peninsula, winding a way on back

lanes to reach the dock at Brandon for the 5 minute ferry crossing over the

narrow channel to the Limfjord island of Fur

(Photo

12 - Fur Island ferry) (see left). We wound a way around the island's

lanes over to the north coast, ending at Fur Camping. The grassy camping areas were tiered up the

steep hill-side, but we managed

to find a pitch that was not unduly sloping or vulnerable to noise from

holiday-making Danes in the many statics. The place had changed drastically from

the straightforward and untamed wooded campsite recalled from our 2007 visit to

Fur; it was then called Råkilde Camping, with a charactersome back-woodsman

owner. In contrast however, it was now very much a Danish holiday-camp, extended in terraces up the

hillside, with a different atmosphere, different clientele, and very different

owners as we were shortly to discover.

Offensively ill-mannered owners at Fur

Camping - a place to be avoided: our plan had been to stay

a second night at Fur Camping, and to undertake the coastal walk around northern

Fur's moler cliffs. But when Paul went over for his shower at 10-30am, he

discovered that the

WC/showers were closed for cleaning until 11-30, peak demand

time. Not prepared to waste time like this, he persuaded the cleaner to let him

use one of the showers, but Sheila was unable to get her shower. We packed our

kit for today's walk, but before leaving, went over to reception to raise the

issue of closing WC/showers to paying guests at peak times to suit management

convenience. Both the owner and his wife now turned insultingly rude, and

demanded we leave immediately for presuming to question the way they ran their

campsite. The more we remonstrated, the more offensive they became, obdurately

insisting we leave immediately, with no payment required for last night. In over

40 years of camping, this was the most grotesquely ill-mannered behaviour we had

ever encountered from campsite owners; not prepared to accept such uncouth

attitudes towards paying guests who kept them in WC/showers were closed for cleaning until 11-30, peak demand

time. Not prepared to waste time like this, he persuaded the cleaner to let him

use one of the showers, but Sheila was unable to get her shower. We packed our

kit for today's walk, but before leaving, went over to reception to raise the

issue of closing WC/showers to paying guests at peak times to suit management

convenience. Both the owner and his wife now turned insultingly rude, and

demanded we leave immediately for presuming to question the way they ran their

campsite. The more we remonstrated, the more offensive they became, obdurately

insisting we leave immediately, with no payment required for last night. In over

40 years of camping, this was the most grotesquely ill-mannered behaviour we had

ever encountered from campsite owners; not prepared to accept such uncouth

attitudes towards paying guests who kept them in business, we did indeed depart, vowing to

ensure that the world knew of their intemperate lack of any grace or civility.

We urge all other campers to avoid Fur Camping like the plague, so that such

ill-mannered people learn to their cost the commercial consequences of treating

customers in such insulting terms. business, we did indeed depart, vowing to

ensure that the world knew of their intemperate lack of any grace or civility.

We urge all other campers to avoid Fur Camping like the plague, so that such

ill-mannered people learn to their cost the commercial consequences of treating

customers in such insulting terms.

Fur moler cliffs: we drove around to the parking area at the Fur

northern cliff-top for the start of today's walk around the moler cliffs, and

here found an ideal spot for a wild camp tonight: the parking area was labelled

on the Fur tourist map-leaflet as a Primitiv Overnatningplads. Assured by

this, we set off for our cliff-top walk.

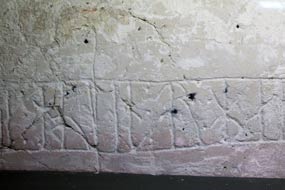

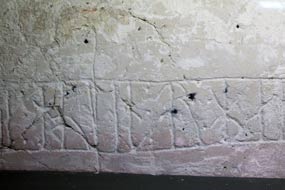

The cliffs of Mors and Fur, islands set in

Limfjord, show a unique geological feature, being composed of moler-clay, a

sedimentary rock laid down some 50 million years ago in a shallow sub-tropical

sea which then covered Denmark. It is formed of a mixture of fine clay particles

and Diatomaceous Earth (kieselgur), the fossilised siliceous remains of

diatoms, hard-shelled single cell creatures. Here on the northern cliffs of

Fur, the moler-clay is interspersed with strata of grey volcanic ash deposited

during the clay's formation. The seas in which the sediments were formed were

rich in plant and animal life, and the deposits of moler-clay now reveal a

wealth of fossilised remains. The moler-clay was quarried extensively during the

20th century, and used for thermal insulation and industrial absorbency

applications, including the manufacture of cat litter; Nobel made dynamite by

absorbing nitro-glycerine in diatomite. The remains of former moler-clay

extraction quarries still exist in the northern hills of Fur just inland from

the cliffs, and the strata of moler-clay interspersed with grey volcanic ash,

thrust up and contorted into vertical planes, are exposed on the high cliff

faces of northern Fur where we planned to walk today. thermal insulation and industrial absorbency

applications, including the manufacture of cat litter; Nobel made dynamite by

absorbing nitro-glycerine in diatomite. The remains of former moler-clay

extraction quarries still exist in the northern hills of Fur just inland from

the cliffs, and the strata of moler-clay interspersed with grey volcanic ash,

thrust up and contorted into vertical planes, are exposed on the high cliff

faces of northern Fur where we planned to walk today.

From the parking area, we followed the clearly

marked cliff-top path which rose and dipped through woodland, with occasional

views over the cliff-edge.

Inland from here, but unseen among the dense

woodland, were the remains of Fur's former moler-clay quarry pits. The cliffs

gained in height, finally emerging clear of the trees at the highest point of

the cliff-line; here at Knudeklinterne, the most impressive view of the

cliff-face became visible, revealing the alternating strata of creamy-coloured

moler-clay and grey volcanic ash (see above right)

(Photo

13 - Fur moler cliffs). Huge gashes in the upper part of the

cliff-face suggested that these had been quarried out. Beyond here, the

cliff-top path was ablaze with purple Heather (see above left) and Sea Buckthorn bushes laden

with orange berries. The height of the cliffs gradually reduced as we approached

and rounded the NW tip of the island, dropping down towards sea level at

Lille Knudshoved. Along the shore line, past dense thickets of sweetly-scented

wild roses, we turned inland to Fur Brewery where we Inland from here, but unseen among the dense

woodland, were the remains of Fur's former moler-clay quarry pits. The cliffs

gained in height, finally emerging clear of the trees at the highest point of

the cliff-line; here at Knudeklinterne, the most impressive view of the

cliff-face became visible, revealing the alternating strata of creamy-coloured

moler-clay and grey volcanic ash (see above right)

(Photo

13 - Fur moler cliffs). Huge gashes in the upper part of the

cliff-face suggested that these had been quarried out. Beyond here, the

cliff-top path was ablaze with purple Heather (see above left) and Sea Buckthorn bushes laden

with orange berries. The height of the cliffs gradually reduced as we approached

and rounded the NW tip of the island, dropping down towards sea level at

Lille Knudshoved. Along the shore line, past dense thickets of sweetly-scented

wild roses, we turned inland to Fur Brewery where we paused for glasses of the

micro-brewery's beers (see above right). A path led through the former moler-clay

quarry pits up through the woods to our start-point on the low cliff-top where

wild Honeysuckle flourished (see left)

(Photo

14 - Wild Honeysuckle) paused for glasses of the

micro-brewery's beers (see above right). A path led through the former moler-clay

quarry pits up through the woods to our start-point on the low cliff-top where

wild Honeysuckle flourished (see left)

(Photo

14 - Wild Honeysuckle)

Wild camp at Fur moler-cliffs:

back at the cliff-top parking area just behind the shingle beach, we set up camp

just in time as the forecast rain began in earnest. With the heavily overcast

sky, dusk seemed to fall earlier on such a gloomy evening. We were undisturbed

at our peaceful wild camp

spot, and woke to a bright, sunny morning interspersed

with downpour showers brought in by the brisk SW wind. Before leaving, we walked

down to the beach for photos looking along the line of Northern Fur's moler

cliffs and out across the inland sea of Limfjord (see left). This had been a magnificent

spot to camp (see right) (Photo

15 - Fur wild camp). spot, and woke to a bright, sunny morning interspersed

with downpour showers brought in by the brisk SW wind. Before leaving, we walked

down to the beach for photos looking along the line of Northern Fur's moler

cliffs and out across the inland sea of Limfjord (see left). This had been a magnificent

spot to camp (see right) (Photo

15 - Fur wild camp).

A return visit to Nørre Vorupør on the North-West Jutland coast:

with the squally showers continuing, we crossed back from Fur on the ferry to Brandon on the Selling peninsula

through a network of lanes and small villages to rejoin the main Route 26 over

the wooded, hilly island of Mors (click

here for detailed map of route). Re-crossing the Vilsund girder-bridge,

we turned off northwards alongside Thisted Bredning into the town of Thisted to

shop for provisions at the Brugsen supermarket. From here we headed west on

Route 539 through the Thy heath-land across to Nørre Vorupør on the NW Jutland

coast, to buy smoked fish

and the best fish-cakes ever tasted at our favourite fish smoke-house (røgeri),

with its sign promoting Alt Godt fra Havet (Everything Good from the Sea) (Photo

16 - Nørre Vorupør Røgeri) (see right).

Klitmøller and Nørre Vorupør are

two of several Jutland fishing villages without a harbour, where boats are still

dragged up and launched

from the beach, and we had to make a nostalgic re-visit to Nørre Vorupør

beach to photograph (yet again) the fishing boats drawn up on the sands (see Thisted Bredning into the town of Thisted to

shop for provisions at the Brugsen supermarket. From here we headed west on

Route 539 through the Thy heath-land across to Nørre Vorupør on the NW Jutland

coast, to buy smoked fish

and the best fish-cakes ever tasted at our favourite fish smoke-house (røgeri),

with its sign promoting Alt Godt fra Havet (Everything Good from the Sea) (Photo

16 - Nørre Vorupør Røgeri) (see right).

Klitmøller and Nørre Vorupør are

two of several Jutland fishing villages without a harbour, where boats are still

dragged up and launched

from the beach, and we had to make a nostalgic re-visit to Nørre Vorupør

beach to photograph (yet again) the fishing boats drawn up on the sands (see

below left) (Photo

17 - Fishing boats at Nørre Vorupør beach).

Even on a sunny day, the

enclosed bay receives the

full force of the brisk westerly winds

which blow constantly

on

this magnificent coast-line, driving

huge breakers pounding towards the beach, and attracting

kite-surfers who hurtle across the bay

taking advantage of the wind and surf. below left) (Photo

17 - Fishing boats at Nørre Vorupør beach).

Even on a sunny day, the

enclosed bay receives the

full force of the brisk westerly winds

which blow constantly

on

this magnificent coast-line, driving

huge breakers pounding towards the beach, and attracting

kite-surfers who hurtle across the bay

taking advantage of the wind and surf.

A day in camp at Krohavens Camping at Stenbjerg:

just down the coast road from Nørre Vorupør, we turned off to Stenbjerg to find

Krohavens Camping, tucked away behind Stenbjerg Kro hotel-restaurant. We had first

discovered this homely site on our return from Norway in 2014, and had stayed

there again on our way to and from Hirtshals for the crossing to Faroes and

Iceland in 2017. Concerned now that the place we had such fond

recollections of might have changed, we turned into the campsite. Opening hours at reception late in the

season were limited, and a notice advised us to select our pitch and book in

later; round at the camping area, all was thankfully as we remembered, other

than the inevitable increase in statics. The large, flat grassy pitches were

enclosed by hedges of sweetly-scented wild roses, and with the brisk SW wind

still blowing from across the open heath-land to the rear, we tucked George into

the shelter of the hedge at our usual place

(Photo

18 - Krohavens Camping at Stenbjerg) (see right); it was good to be back. The stiff

wind off the sea continued all evening bringing in heavy cloud and a lot of

overnight rain. now that the place we had such fond

recollections of might have changed, we turned into the campsite. Opening hours at reception late in the

season were limited, and a notice advised us to select our pitch and book in

later; round at the camping area, all was thankfully as we remembered, other

than the inevitable increase in statics. The large, flat grassy pitches were

enclosed by hedges of sweetly-scented wild roses, and with the brisk SW wind

still blowing from across the open heath-land to the rear, we tucked George into

the shelter of the hedge at our usual place

(Photo

18 - Krohavens Camping at Stenbjerg) (see right); it was good to be back. The stiff

wind off the sea continued all evening bringing in heavy cloud and a lot of

overnight rain.

When reception opened the following morning at

8-00am, we went up to pay with the pleasantly welcoming owner Henny Mortensen: prices had remained

constant at 155kr (plus 5kr coins for showers) for as long as

we could recall, making Krohavens Camping surely one of the best value and

pleasantly located campsites in the whole of Denmark. The facilities were first

class with well-equipped kitchen/wash-up and cosy common room (newly fitted out

in 2017 and still as good as ever), homely, modern and spotlessly clean

WC/showers, and to top it all one of the few Danish campsites with full,

site-wide wifi; Krohavens was a first site rate campsite and worthily rated by

us at +5, a Danish favourite. Today the sun shone and we spent a much-needed and

productive day in camp in such a pleasant and peaceful setting at Stenbjerg. When reception opened the following morning at

8-00am, we went up to pay with the pleasantly welcoming owner Henny Mortensen: prices had remained

constant at 155kr (plus 5kr coins for showers) for as long as

we could recall, making Krohavens Camping surely one of the best value and

pleasantly located campsites in the whole of Denmark. The facilities were first

class with well-equipped kitchen/wash-up and cosy common room (newly fitted out

in 2017 and still as good as ever), homely, modern and spotlessly clean

WC/showers, and to top it all one of the few Danish campsites with full,

site-wide wifi; Krohavens was a first site rate campsite and worthily rated by

us at +5, a Danish favourite. Today the sun shone and we spent a much-needed and

productive day in camp in such a pleasant and peaceful setting at Stenbjerg.

A day's walking in Thy National Park:

we woke to a heavily overcast morning with cool breeze, but the forecast was for a sunny day for our planned day's walking in the Thy

(pronounced as in French Tu) National Park dune heath-land.

The coastal area of NW Jutland such as the Stenbjerg Klitplantage (dune

plantation), where we should walk today, is largely seafloor uplift created

during the post-glacial land rise. It is therefore mostly sandy with the terrain

ranging from flat heath-land to extensive areas of dunes. The coastal cliffs of

the ancient pre-land uplift sea are still visible but now 6kms inland. Eastward

of this line, the soil changes from sand to clay and gravel on chalk, with

completely different vegetation, with the tree species and their growth giving

clear evidence of more fertile growing conditions. When coastal settlements in

Thy such as Stenbjerg began to develop from the end of the 17th

century, the

drifting sands of the coastal strip covered fields, making it impossible to

cultivate the soil, and farming was driven eastward inland. Those who did not

own land managed to settle in the coastal area of drifting sands, and eked out a

survival living from fishing and whatever could be cultivated on the poor soil.

In the early 19th century, as part of the constant battle against drifting sand,

local people began planting trees in the otherwise treeless landscape of the

coastal strip dunes. From the late 19th through 20th centuries, the sand drift

along the coastal belt was gradually consolidated by rolling out a plantation

carpet of Mountain Pines across the landscape. Gradually, as the plantations of

trees provided shelter from winds and frost, other species such as Spruce, Scots

Pine and deciduous trees (mainly Oak) could be introduced. century, the

drifting sands of the coastal strip covered fields, making it impossible to

cultivate the soil, and farming was driven eastward inland. Those who did not

own land managed to settle in the coastal area of drifting sands, and eked out a

survival living from fishing and whatever could be cultivated on the poor soil.

In the early 19th century, as part of the constant battle against drifting sand,

local people began planting trees in the otherwise treeless landscape of the

coastal strip dunes. From the late 19th through 20th centuries, the sand drift

along the coastal belt was gradually consolidated by rolling out a plantation

carpet of Mountain Pines across the landscape. Gradually, as the plantations of

trees provided shelter from winds and frost, other species such as Spruce, Scots

Pine and deciduous trees (mainly Oak) could be introduced.

The large areas of sandy heath-land are a

characteristic feature of Thy National Park, with distinctive flora and fauna

adapted to this habitat of sandy dunes, heath-land, heather and bog. Typical

plants are Ling, Crowberry, Bog-bilberry, Cranberry and Sundew. Today many of

the sandy dune areas need regular management to avoid overgrowth of

vegetation, with clearance of Mountain Pine and other non-native species which

invade from the older plantations. In the outer dune seaward areas, another

man-made problem has been the invasion of thickets of the wild Rugosa

Rose. In the 1950s this hardy species, introduced from its native eastern Asia, was planted as hedges around holiday

houses, and has now invasively spread so uncontrollably to surrounding natural

areas of dune habitat that it threatens the original dune character and unique

natural flora. While we associate the sweetly-scented wild Rugosa Rose thickets

with coastal areas of Denmark, it has now become necessary to carry out large

scale cutting back to control this extensively invasive spread. Sundew. Today many of

the sandy dune areas need regular management to avoid overgrowth of

vegetation, with clearance of Mountain Pine and other non-native species which

invade from the older plantations. In the outer dune seaward areas, another

man-made problem has been the invasion of thickets of the wild Rugosa

Rose. In the 1950s this hardy species, introduced from its native eastern Asia, was planted as hedges around holiday

houses, and has now invasively spread so uncontrollably to surrounding natural

areas of dune habitat that it threatens the original dune character and unique

natural flora. While we associate the sweetly-scented wild Rugosa Rose thickets

with coastal areas of Denmark, it has now become necessary to carry out large

scale cutting back to control this extensively invasive spread.

Our

day in Stenbjerg Klitplantage, Thy National Park: from the parking area just off the Route

181 Kystvej (coast road), we set off on the circular Bislet Trail through the

heather-covered sandy heath of Stenbjerg Klitplantage (dune plantation). This

forested sandy dune heath included areas of plantation which illustrated the

progression of plantation periods throughout the 20th century, and so included a

number of Pine and Spruce species and later plantation of broad-leafed species,

mainly Oak. We had walked this circuit through the dune heath woodland on

previous visits in late September, but being slightly earlier this year in

mid-August, the Ling was in full bloom, carpeting the sandy ground with

purple

(see above left and right) (Photo

19 - Heather in full bloom). It also showed how the planted trees so rapidly spread, with many low

Pine and Oak young seedlings among the ground cover of scrub vegetation. On a

sunny afternoon, this was a truly delightful walk through the sandy heath

landscape that illustrated the history of taming and managing the Thy coastal

dunes. A Our

day in Stenbjerg Klitplantage, Thy National Park: from the parking area just off the Route

181 Kystvej (coast road), we set off on the circular Bislet Trail through the

heather-covered sandy heath of Stenbjerg Klitplantage (dune plantation). This

forested sandy dune heath included areas of plantation which illustrated the

progression of plantation periods throughout the 20th century, and so included a

number of Pine and Spruce species and later plantation of broad-leafed species,

mainly Oak. We had walked this circuit through the dune heath woodland on

previous visits in late September, but being slightly earlier this year in

mid-August, the Ling was in full bloom, carpeting the sandy ground with

purple

(see above left and right) (Photo

19 - Heather in full bloom). It also showed how the planted trees so rapidly spread, with many low

Pine and Oak young seedlings among the ground cover of scrub vegetation. On a

sunny afternoon, this was a truly delightful walk through the sandy heath

landscape that illustrated the history of taming and managing the Thy coastal

dunes. A

side-path climbed to the top of a particularly high dune, giving

extensive views over the tree-tops of older planted tall Pines. The dry,

nutrient-deficient sandy slopes of the dune hill supported the growth of

flourishing patches of Reindeer lichen (Cladonia rangiformis), previously

seen by us growing in the Arctic. Butterflies (Peacock, Painted Lady and Red

Admiral) flitted around us as we continued

around the circuit, revelling in this sunny wonderland carpeted with scented

heather and bright yellow Toadflax (see above left), following the path to the reed-beds of Bislet lake

(see above right) where the flora

changed to that characteristic of wetter areas. side-path climbed to the top of a particularly high dune, giving

extensive views over the tree-tops of older planted tall Pines. The dry,

nutrient-deficient sandy slopes of the dune hill supported the growth of

flourishing patches of Reindeer lichen (Cladonia rangiformis), previously

seen by us growing in the Arctic. Butterflies (Peacock, Painted Lady and Red

Admiral) flitted around us as we continued

around the circuit, revelling in this sunny wonderland carpeted with scented

heather and bright yellow Toadflax (see above left), following the path to the reed-beds of Bislet lake

(see above right) where the flora

changed to that characteristic of wetter areas.

We drove around to Route 571 Stenbjergvej to

the parking area for the circular Løvbakke and Embak walking routes, again

through 20th century plantation forests of the Stenbjerg Klitplantage sandy dune

heath-land. Although similar to the first walk, this terrain was more densely

planted, an obvious

plantation with less variety of flora and wetter ground. But

among the Ling here, Cross-leaved Heath (Erica tetralix) grew (see above

left) with its delicate pale-lilac

lantern-shaped flowers closely resembling those of Bearberry (another Ericaceae species). plantation with less variety of flora and wetter ground. But

among the Ling here, Cross-leaved Heath (Erica tetralix) grew (see above

left) with its delicate pale-lilac

lantern-shaped flowers closely resembling those of Bearberry (another Ericaceae species).

We drove back to the coast at Stenbjerg

Landingsplads where on a sunny September afternoon in 2017 we had sat to enjoy

lakrids (liquorice) ice cream from the National Park information hut. But

disappointment: this year the kiosk had closed at 4-00pm. Instead we walked down

to the deserted beach, where once fishing boats had been dragged up onto the sands

(see above right)

(Photo

20 - Stenbjerg Landingsplads). The

conserved fishing huts at Stenbjerg landing place alongside the Stenbjerg

life-boat station were built by Thy fishermen around 1900 to provide cover for

storing and maintaining nets and tackle. This was the time

when the advent of motorised vessels made possible the transition to fishing by

nets replacing line-fishing. Commercial fishing by larger boats ended at Stenbjerg

Landingsplads in 1972, but the

huts were restored and conserved and are still used by anglers. Today had been a

truly enjoyable day of walking in the Stenbjerg dune plantations; tomorrow we

continue our Jutland journey, around the northern shore of Limfjord for a return

stay at Løgstør. anglers. Today had been a

truly enjoyable day of walking in the Stenbjerg dune plantations; tomorrow we

continue our Jutland journey, around the northern shore of Limfjord for a return

stay at Løgstør.

North to the fishing port of Hanstholm:

on a heavily overcast morning with a cool wind as always blowing from the SW, we began today's drive

northwards up the Route 181 Kystvej (coast road) towards Hanstholm (click

here for detailed map of route). This led

initially through the tree-covered Tvorup Klintplantage (dune plantation) of

mature Pine and Spruce, the oldest plantations in Thy dating from the

late

19th century, bordering the sea to the west and extending eastwards to the

inland agricultural land. The road then reached the broad areas of sandy dune

heath-land (klit hede in Danish), bare of trees and covered with rough

grass in contrast with the klit plantage's covering of Pine, Spruce and

Oak through which we had walked yesterday. The dune heath-land is mown and

burned to keep it free from unwanted trees. We continued through the Hanstholm dune heath-lands to turn off into the major fishing port of Hanstholm. Ironically the town's

main tourist attraction today are the WW2 fortifications and gigantic gun-emplacements

built by the German occupiers in 1941 as part of the Atlantic Wall. High German

wages tempted Danish workers to participate alongside Soviet POW slave-labour

in the construction of this huge complex. Hanstholm's civilian population however suffered a cruel fate with homes and

livelihood destroyed by evacuation to hastily-built camps, late

19th century, bordering the sea to the west and extending eastwards to the

inland agricultural land. The road then reached the broad areas of sandy dune

heath-land (klit hede in Danish), bare of trees and covered with rough

grass in contrast with the klit plantage's covering of Pine, Spruce and

Oak through which we had walked yesterday. The dune heath-land is mown and

burned to keep it free from unwanted trees. We continued through the Hanstholm dune heath-lands to turn off into the major fishing port of Hanstholm. Ironically the town's

main tourist attraction today are the WW2 fortifications and gigantic gun-emplacements

built by the German occupiers in 1941 as part of the Atlantic Wall. High German

wages tempted Danish workers to participate alongside Soviet POW slave-labour

in the construction of this huge complex. Hanstholm's civilian population however suffered a cruel fate with homes and

livelihood destroyed by evacuation to hastily-built camps, enforced by the collaborationist Danish government in compliance with German

demands. We saw from our 2007 visit that the WW2 museum presents a curiously