|

CAMPING

IN ICELAND 2017 - SnŠfellsnes Peninsula and West Iceland: EirÝksstair, Reykholt, Borgarfj÷rur, Eldborg Crater, Arnarstapi and Hellnar,

Hellissandur, Grundarfj÷rur, Stykkishˇlmur,

Borgarnes and Hvalfj÷rur: CAMPING

IN ICELAND 2017 - SnŠfellsnes Peninsula and West Iceland: EirÝksstair, Reykholt, Borgarfj÷rur, Eldborg Crater, Arnarstapi and Hellnar,

Hellissandur, Grundarfj÷rur, Stykkishˇlmur,

Borgarnes and Hvalfj÷rur:

South from Reykhˇlar:

after our relaxing couple of days enjoying the warm weather and bird-life at

peaceful Reykhˇlar, we returned around the Reykjanes peninsula coastline to

re-join the main Route 60 at Bjarkarlundar. It was another beautiful morning:

the sky was clear with bright sunshine, the valleys looked green against the

misty, stark, craggy mountains, and the fjord reflected the blue sky. Farmers

had been taking full advantage of the few days of fine weather for hay-making,

and fjord-side fields were dotted with plastic-covered hay bales (see left). South from Reykhˇlar:

after our relaxing couple of days enjoying the warm weather and bird-life at

peaceful Reykhˇlar, we returned around the Reykjanes peninsula coastline to

re-join the main Route 60 at Bjarkarlundar. It was another beautiful morning:

the sky was clear with bright sunshine, the valleys looked green against the

misty, stark, craggy mountains, and the fjord reflected the blue sky. Farmers

had been taking full advantage of the few days of fine weather for hay-making,

and fjord-side fields were dotted with plastic-covered hay bales (see left).

|

Click on the 4 highlighted areas of map

for

details of

SnŠfellsnes Peninsula |

|

The White-Tailed Eagles Centre at Krˇksfjararnes:

there was little traffic as we drove around the coastal strip of Krˇksfj÷rur,

dropping down to the tiny settlement of Krˇksfjararnes (Click on Map 1 right). Just before the

village, the newly engineered Route 61 branched off along Gautsdalur towards

HolmavÝk, the route taken by all the Icelandic holiday -making caravans from the

ReykjavÝk conurbation. We had seen reference to a White-Tailed Eagles

Centre in the Gamla KaupfÚlagsh˙si (Old Shop-house) at Krˇksfjararnes, but had

been unable to find any details. We turned off the main road into the scattered

village, found the old shop, and sure enough the sign in the window announced Arnarsetur Eagle Centre. The former village shop had closed, but had re-opened

as a community enterprise selling handicraft works, with locally made genuine

Icelandic sweaters (so much of the knitwear ubiquitously sold at enormous

expense to tourists are

far eastern imports). We were graciously welcomed, to be told that a local

person organised the displays and information panels about White-Tailed Eagles;

being now protected, these magnificent birds of prey are now nesting again in

ever greater numbers around Breiafj÷rur. -making caravans from the

ReykjavÝk conurbation. We had seen reference to a White-Tailed Eagles

Centre in the Gamla KaupfÚlagsh˙si (Old Shop-house) at Krˇksfjararnes, but had

been unable to find any details. We turned off the main road into the scattered

village, found the old shop, and sure enough the sign in the window announced Arnarsetur Eagle Centre. The former village shop had closed, but had re-opened

as a community enterprise selling handicraft works, with locally made genuine

Icelandic sweaters (so much of the knitwear ubiquitously sold at enormous

expense to tourists are

far eastern imports). We were graciously welcomed, to be told that a local

person organised the displays and information panels about White-Tailed Eagles;

being now protected, these magnificent birds of prey are now nesting again in

ever greater numbers around Breiafj÷rur.

We watched the video about White-Tailed Eagles; although only in Icelandic, we could follow the gist. With a wing span of

up to 2.5m, White-Tailed Eagles (known also as Sea Eagles) (see left) feed on both carrion

and hunt live prey, either fish or birds, mainly Eiders or Fulmars; they are

non-migratory and pairs mate for life. This admirably unpretentious little

museum at Krˇksfjararnes, which charges only 250kr for admission, deserves

greater recognition. As we sat outside in the sunshine to eat our lunch

sandwiches after our visit. we chatted with the girl who had welcomed us; it

turned out she was German, who had come originally as a back-packing traveller,

and had stayed for the summer to work here at the handicraft shop. If you pass

this way en route to or from the West Fjords, make a point of stopping for

coffee and cakes at this worthy community venture. Fulmars; they are

non-migratory and pairs mate for life. This admirably unpretentious little

museum at Krˇksfjararnes, which charges only 250kr for admission, deserves

greater recognition. As we sat outside in the sunshine to eat our lunch

sandwiches after our visit. we chatted with the girl who had welcomed us; it

turned out she was German, who had come originally as a back-packing traveller,

and had stayed for the summer to work here at the handicraft shop. If you pass

this way en route to or from the West Fjords, make a point of stopping for

coffee and cakes at this worthy community venture.

South to B˙ardalur for provisions re-stock:

Route 60 crossed the mouth of Gilsfj÷rur on a 4kms long causeway (see right) and, amid

stately hills, climbed steadily up into the depths of Hvolsdalur, gaining height

to cross the Hˇlknaheii watershed, for the long descent of SvÝnadalur down to

the shores of Hvammsfj÷rur, the innermost corner of the vast Breiafj÷rur, to reach the

large village of B˙ardalur (click

here for detailed map of route). Along the main road, we found a Samkaup-Strax

supermarket and filling station, for us to stock up with provisions at very

expensive prices and to re-fill George with diesel. This place was clearly

exploiting the tourist traffic and holiday-makers who pass along this main road. the shores of Hvammsfj÷rur, the innermost corner of the vast Breiafj÷rur, to reach the

large village of B˙ardalur (click

here for detailed map of route). Along the main road, we found a Samkaup-Strax

supermarket and filling station, for us to stock up with provisions at very

expensive prices and to re-fill George with diesel. This place was clearly

exploiting the tourist traffic and holiday-makers who pass along this main road.

EirÝksstair in Haukadalur:

20kms south of B˙ardalur, we turned off into the broad, green farming valley of

Haukadalur (see left and right), and 8 kms along the dale on a dusty dirt road we reached the site of

what has been interpreted from a tentative reference in one of the Sagas as EirÝksstair, the

farmstead of EirÝk the Red, father of Leifur EirÝksson. The Norse Viking, EirÝk

the Red (EirÝk Ůorvalsson 950~1003 AD) had, according to the Icelandic Book of

Settlements (the Landnßmabˇk), originally settled in Hornstrandir in the West

Fjords after his father had been exiled from his native Norway for murder. EirÝk

moved to Haukadalur after marrying into a land-owning family there. and built a farmstead which he named EirÝksstair. But, a violent and ill-tempered man,

he was exiled from Haukadalur after murdering several neighbours in a dispute.

He moved to SnŠfellsnes from where, after committing further acts of murder, he

was exiled again. With a shipload of comrades, he set sail westwards discovering

new lands where, of

Haukadalur (see left and right), and 8 kms along the dale on a dusty dirt road we reached the site of

what has been interpreted from a tentative reference in one of the Sagas as EirÝksstair, the

farmstead of EirÝk the Red, father of Leifur EirÝksson. The Norse Viking, EirÝk

the Red (EirÝk Ůorvalsson 950~1003 AD) had, according to the Icelandic Book of

Settlements (the Landnßmabˇk), originally settled in Hornstrandir in the West

Fjords after his father had been exiled from his native Norway for murder. EirÝk

moved to Haukadalur after marrying into a land-owning family there. and built a farmstead which he named EirÝksstair. But, a violent and ill-tempered man,

he was exiled from Haukadalur after murdering several neighbours in a dispute.

He moved to SnŠfellsnes from where, after committing further acts of murder, he

was exiled again. With a shipload of comrades, he set sail westwards discovering

new lands where,

according to the Saga of the Greenlanders, he settled naming

the country Greenland to entice other settlers to follow. His son Leifur

EirÝksson, who had been born at EirÝksstair

around 980 AD and moved with his father to Greenland, set out also to sail

further westwards, discovering new lands in 1000 AD thought to be along the

Labrador coast of North America, which he named Markland (Forest Land). Sailing on, he reached more fertile lands

where wild vines are said by the Sagas to have grown; he accordingly named the

land Vinland. Leifur

EirÝksson attempted to establish a colony there, but this lasted for no

more than a generation. Among his fellow settlers in the New World were Ůorfinnur Karlsefni and GurÝur Ůorbjarnardˇttir, who according to the Saga of the Greenlanders, he settled naming

the country Greenland to entice other settlers to follow. His son Leifur

EirÝksson, who had been born at EirÝksstair

around 980 AD and moved with his father to Greenland, set out also to sail

further westwards, discovering new lands in 1000 AD thought to be along the

Labrador coast of North America, which he named Markland (Forest Land). Sailing on, he reached more fertile lands

where wild vines are said by the Sagas to have grown; he accordingly named the

land Vinland. Leifur

EirÝksson attempted to establish a colony there, but this lasted for no

more than a generation. Among his fellow settlers in the New World were Ůorfinnur Karlsefni and GurÝur Ůorbjarnardˇttir, who after the Vinland settlement's failure returned to Iceland in

the early years of the 11th century and settled at GlaumbŠr (See

log of our visit to GlaumbŠr); their infant

son Snorri Ůorfinnson was born at Vinland in 1003 AD becoming the first European born in

America, 500 years before Columbus re-discovered the continent. The unknown

location of Vinland remains a subject of speculation and controversy. after the Vinland settlement's failure returned to Iceland in

the early years of the 11th century and settled at GlaumbŠr (See

log of our visit to GlaumbŠr); their infant

son Snorri Ůorfinnson was born at Vinland in 1003 AD becoming the first European born in

America, 500 years before Columbus re-discovered the continent. The unknown

location of Vinland remains a subject of speculation and controversy.

Excavations at Haukadalur in the late 1990s

revealed a Viking era longhouse (skßli), and although there is no direct

evidence to link the site to EirÝk the Red, the place has been named EirÝksstair.

And the tourism industry rubbed its itchy hands with glee as the tourists

flocked in. We drove along the valley on the dusty dirt road past Haukadalsvatn

to reach the EirÝksstair parking area, large enough to accommodate a whole

fleet of tour buses. Up a hill-side path, past the over-stylised, twee statue of EirÝk

the Red standing at the prow of his long ship,

we found the site of the

archaeological excavation. The view looking along the broad, fertile valley was

even more striking; you could understand why sea-born settlers had chosen this

dale for their farmsteads. A modern replica of the turf-roofed long-house had

been constructed nearby (see above left and right) (Photo 1 - EirÝksstair reconstruction),

attended

by unconvincingly costumed modern-day 'Vikings',

one of whom had we had seen in the supermarket at B˙ardalur! This was clearly

little more than an over-priced tourist attraction and of little interest to us;

the unpretentious farmstead at GlaumbŠr (GlaumbŠr turf-walled farmstead museum)

was far more educative than the over-hyped imitation at EirÝksstair

with little evidence to support we found the site of the

archaeological excavation. The view looking along the broad, fertile valley was

even more striking; you could understand why sea-born settlers had chosen this

dale for their farmsteads. A modern replica of the turf-roofed long-house had

been constructed nearby (see above left and right) (Photo 1 - EirÝksstair reconstruction),

attended

by unconvincingly costumed modern-day 'Vikings',

one of whom had we had seen in the supermarket at B˙ardalur! This was clearly

little more than an over-priced tourist attraction and of little interest to us;

the unpretentious farmstead at GlaumbŠr (GlaumbŠr turf-walled farmstead museum)

was far more educative than the over-hyped imitation at EirÝksstair

with little evidence to support its tourist-focussed claim to links with EirÝk

the Red and Leifur EirÝksson. its tourist-focussed claim to links with EirÝk

the Red and Leifur EirÝksson.

South to re-join Route 1 Ring road: back along the valley, we continued south on Route 60 ,

with speeding Icelandic holiday-making traffic now increasing, and turned off at

one of the valley dairy farms, Erpsstair, to sample its renowned home-made

ice-cream (see left). Route 60 now climbed lustily over a high pass, amid

spectacular mountain terrain (see right) (click

here for detailed map of route), to descend the long, steep southern side passing

an impressive gorge carved out by the river torrent dropping from the

watershed. This long descent brought us down regrettably to re-join Route 1 Ring

Road, which we had left 3 weeks ago at Bru. ReykjavÝk-bound traffic now became

horribly oppressive, with equally stressful driving standards. It was thoroughly

unpleasant, and will from now only get worse as we approach the capital. As we

turned south onto the Ring Road, the nature of the terrain changed suddenly from

green, rolling hills to the volcanic lava fields of Grßbrˇkarhraun (see below left), with an evident

ash-cone by the road side. 10 kms further and the lava field

ended equally suddenly as we approached the turn-off onto Route 50.

A

miserably crowded and noisy stay at the dreadful Varmaland Camping:

crossing the salmon-rich wide River Norurß, we turned off to find tonight's campsite at Varmaland, a huge geothermal swimming pool with attached so-called 'campsite'.

Being relatively close to ReykjavÝk, this was A

miserably crowded and noisy stay at the dreadful Varmaland Camping:

crossing the salmon-rich wide River Norurß, we turned off to find tonight's campsite at Varmaland, a huge geothermal swimming pool with attached so-called 'campsite'.

Being relatively close to ReykjavÝk, this was bound to attract holiday-making

crowds from the conurbation. We had little expectations of the place, but it was

even worse than we could have conceived: it was nothing more than an enormous

rough field alongside the swimming pool complex, crammed full of caravans and

luxury trailer-tents, the sort of fun-loving, materialistically-minded, rowdy

folk we should normally run a million miles to escape from, except that for

tonight there was no such escape. This was the only place to camp in the

vicinity, and we just about managed to find a reasonably quiet spot in the far

corner looking out across farmland to a distant horizon of volcanic mountains

(see right).

With heavy hearts we settled in. There was of course no power supplies in this

corner and the distant facilities were limited to WC and a geothermally heated

wash-up sink. Even so, with a captive audience of such massed holiday-makers,

prices were appallingly expensive, but at least the Camping Card was accepted.

But there would be little peace, despite having tent campers as near neighbours.

On a fine, sunny evening we cooked a barbecue supper, and tonight we had just

turned in and got off to sleep when we were wakened by noisy late arrivals

thoughtlessly slamming car doors, until our robust protests caused them to move.

The following morning was hot

bound to attract holiday-making

crowds from the conurbation. We had little expectations of the place, but it was

even worse than we could have conceived: it was nothing more than an enormous

rough field alongside the swimming pool complex, crammed full of caravans and

luxury trailer-tents, the sort of fun-loving, materialistically-minded, rowdy

folk we should normally run a million miles to escape from, except that for

tonight there was no such escape. This was the only place to camp in the

vicinity, and we just about managed to find a reasonably quiet spot in the far

corner looking out across farmland to a distant horizon of volcanic mountains

(see right).

With heavy hearts we settled in. There was of course no power supplies in this

corner and the distant facilities were limited to WC and a geothermally heated

wash-up sink. Even so, with a captive audience of such massed holiday-makers,

prices were appallingly expensive, but at least the Camping Card was accepted.

But there would be little peace, despite having tent campers as near neighbours.

On a fine, sunny evening we cooked a barbecue supper, and tonight we had just

turned in and got off to sleep when we were wakened by noisy late arrivals

thoughtlessly slamming car doors, until our robust protests caused them to move.

The following morning was hot

and sunny and we sat out for breakfast behind

George, out of view of the rowdy hordes. We managed to get a limited wash at the

basic facilities, and were glad to get away from this hideous place and the even

more hideous holiday-makers. and sunny and we sat out for breakfast behind

George, out of view of the rowdy hordes. We managed to get a limited wash at the

basic facilities, and were glad to get away from this hideous place and the even

more hideous holiday-makers.

Deildartunguhver

geothermal source in Borgarfj÷rur: on a

beautifully sunny morning, driving inland across the rolling fertile farmlands

of lower Borgarfj÷rur (click

here for detailed map of route), we could see several steaming geothermal sources dotted across the landscape, and turned off

to Deildartunguhver, Europe's most prolific hot spring. This enormous geothermal

source pumps out 180 litres/second of boiling water (see left), which is conveyed by

insulated pipeline to heat the houses of Akranes 64kms distant and Borgarnes 34kms. We parked by the source but there was now little to see other than the

building works covering the spring outpourings together with the huge clouds of

steam billowing above the splashing boiling water and the start of the pipeline

(Photo 2 - Deildartunguhver geothermal pipeline)

(see right).

The geothermal source is also used to heat nearby market garden green houses growing

vegetables, and we

bought a bag of locally grown geothermal tomatoes from a stall (see below left). Deildartunguhver

geothermal source in Borgarfj÷rur: on a

beautifully sunny morning, driving inland across the rolling fertile farmlands

of lower Borgarfj÷rur (click

here for detailed map of route), we could see several steaming geothermal sources dotted across the landscape, and turned off

to Deildartunguhver, Europe's most prolific hot spring. This enormous geothermal

source pumps out 180 litres/second of boiling water (see left), which is conveyed by

insulated pipeline to heat the houses of Akranes 64kms distant and Borgarnes 34kms. We parked by the source but there was now little to see other than the

building works covering the spring outpourings together with the huge clouds of

steam billowing above the splashing boiling water and the start of the pipeline

(Photo 2 - Deildartunguhver geothermal pipeline)

(see right).

The geothermal source is also used to heat nearby market garden green houses growing

vegetables, and we

bought a bag of locally grown geothermal tomatoes from a stall (see below left).

Reykholt, the farmstead of Snorri Sturluson: 5kms along Route 518 we reached Reykholt, site of

the farmstead estate of Iceland's renowned medieval clan-chieftain (goar),

politician and poet, Snorri Sturluson (1179~1241). Born into the wealthy

land-owning Sturlung family, one of the powerful clans whose feuding wracked

medieval Iceland, Snorri was educated at the cultural centre of Oddi in Reykholt, the farmstead of Snorri Sturluson: 5kms along Route 518 we reached Reykholt, site of

the farmstead estate of Iceland's renowned medieval clan-chieftain (goar),

politician and poet, Snorri Sturluson (1179~1241). Born into the wealthy

land-owning Sturlung family, one of the powerful clans whose feuding wracked

medieval Iceland, Snorri was educated at the cultural centre of Oddi in Southern

Iceland; he married into a wealthy land-owning family at Borg ß Mřrum near

Borgarnes so acquiring wealth and property. He later settled at the church centre

of Reykholt in Borgarfj÷rur, building up the estate, consolidating his grip

on power and wealth, and becoming goar (chieftain) of the Sturlung clan

and in 1215 Lawspeaker of the Al■ing, the Assembly of the Icelandic

Commonwealth. While at Reykholt, Snorri composed his famous Saga works, the

Prose Edda an account of Norse Mythology, Egil's Saga a history of the Viking

Skald court-poet Egil Skallagrimsson, and the Heimskringla a history of the

Kings of Norway. His position of power brought him into contact with King Hßkon

of Norway whose vassal Snorri became. In 1218 he travelled to the Cathedral city

of Nidaros (Trondheim) and the Norwegian court of the teenage King Hßkon at

Bergen, also forming a friendship with Jarl (Earl) Sk˙li, Hßkon's co-regent and

rival for the throne of Norway. Medieval power politics were however a changing

game: Hßkon was playing off the Icelandic clan chieftains against one another to

enhance his hold on power and extend his realm to Iceland. As Lawspeaker, Snorri

fell foul of this and was suborned by King Hßkon to persuade the Southern

Iceland; he married into a wealthy land-owning family at Borg ß Mřrum near

Borgarnes so acquiring wealth and property. He later settled at the church centre

of Reykholt in Borgarfj÷rur, building up the estate, consolidating his grip

on power and wealth, and becoming goar (chieftain) of the Sturlung clan

and in 1215 Lawspeaker of the Al■ing, the Assembly of the Icelandic

Commonwealth. While at Reykholt, Snorri composed his famous Saga works, the

Prose Edda an account of Norse Mythology, Egil's Saga a history of the Viking

Skald court-poet Egil Skallagrimsson, and the Heimskringla a history of the

Kings of Norway. His position of power brought him into contact with King Hßkon

of Norway whose vassal Snorri became. In 1218 he travelled to the Cathedral city

of Nidaros (Trondheim) and the Norwegian court of the teenage King Hßkon at

Bergen, also forming a friendship with Jarl (Earl) Sk˙li, Hßkon's co-regent and

rival for the throne of Norway. Medieval power politics were however a changing

game: Hßkon was playing off the Icelandic clan chieftains against one another to

enhance his hold on power and extend his realm to Iceland. As Lawspeaker, Snorri

fell foul of this and was suborned by King Hßkon to persuade the

Al■ing to

accept Norwegian suzerainty. On his return to Iceland in 1220, he resumed his

duties as Lawspeaker of the Al■ing, but his support for Norway's cause brought

opposition from the other chieftains; the rise to power of Snorri's opponents

resulted in several years of violent clan feuding. By 1237 Snorri was forced to

seek refuge in Norway and he returned to Hßkon's court. But the power rivalry

there between the King and Jarl Sk˙li had erupted Al■ing to

accept Norwegian suzerainty. On his return to Iceland in 1220, he resumed his

duties as Lawspeaker of the Al■ing, but his support for Norway's cause brought

opposition from the other chieftains; the rise to power of Snorri's opponents

resulted in several years of violent clan feuding. By 1237 Snorri was forced to

seek refuge in Norway and he returned to Hßkon's court. But the power rivalry

there between the King and Jarl Sk˙li had erupted into open civil war; because

of Snorri's support for Sk˙li in his unsuccessful bid for royal power, Hßkon

forbade Snorri to leave Norway; Snorri disobeyed this command and sailed back to

Iceland in 1239. Hßkon charged one of Snorri's rival clan chieftains, Gissur

Ůorvalsson, to bring him back dead or alive. Gissur led a band of 70 armed men

to Reykholt, and Snorri was hacked to death in 1241. Hßkon continued suborning

the clan chieftains of Iceland, and in 1262, the Al■ing finally ratified union with

Norway; royal authority was instituted in Iceland, so bringing to an end the Commonwealth

which had ruled Iceland since 980 AD and the Settlement. into open civil war; because

of Snorri's support for Sk˙li in his unsuccessful bid for royal power, Hßkon

forbade Snorri to leave Norway; Snorri disobeyed this command and sailed back to

Iceland in 1239. Hßkon charged one of Snorri's rival clan chieftains, Gissur

Ůorvalsson, to bring him back dead or alive. Gissur led a band of 70 armed men

to Reykholt, and Snorri was hacked to death in 1241. Hßkon continued suborning

the clan chieftains of Iceland, and in 1262, the Al■ing finally ratified union with

Norway; royal authority was instituted in Iceland, so bringing to an end the Commonwealth

which had ruled Iceland since 980 AD and the Settlement.

Set in the broad, open farming valley of

Reykholtsdalur, Reykholt is now a quiet and unassuming cultural centre of

medieval Icelandic studies, the Snorrastofa, with a modern church and exhibition

on the life and works of Snorri Sturluson. We had expected it also to attract

hordes of visitors, but were amazed to find it quiet with just a few cars in the

parking area. Uncertain how superficial or informative the Snorrastofa

exhibition would be, we paid our seniors' admission of 1,000kr and viewed the

presentations. In fact they gave a well-documented account, with full English

translations, not only of Snorri's life, rise to power and his extensive

literary output, but also of power politics in medieval Norway and Iceland, and

the feuding of the Icelandic clan goar which led ultimately to the end

of the Commonwealth and absorption into the Norwegian realm. The weather was now

unbelievably hot with temperature around 23║C. We walked around the landscaped estate and found the pool fed by a hot spring, the Snorralaug, where Snorri is

said to have bathed; a modern statue appeared to show him wearing

estate and found the pool fed by a hot spring, the Snorralaug, where Snorri is

said to have bathed; a modern statue appeared to show him wearing

his dressing

gown, perhaps just having got out of the Snorralaug (see above left). And nearby was the entrance to the tunnel leading to his

farm where he was murdered by Gissur's assassins. his dressing

gown, perhaps just having got out of the Snorralaug (see above left). And nearby was the entrance to the tunnel leading to his

farm where he was murdered by Gissur's assassins.

The Hraunfossar and Barnafoss Waterfalls on

the glacial HvÝtß River:

we continued eastwards on Route 518 (click

here for detailed map of route) with the road rising over higher pasture

land to drop down into the neighbouring upper valley of the glacial HvÝtß River

whose sources rise in the Langj÷kull Glacier. Inland the distant view was dominated by high mountains and the

massive ice-fields of Langj÷kull (see right). 5 kms deeper into the Borgarfj÷rur valley past

several farms, we pulled into a lay-by to visit the waterfalls on the

fast-flowing HvÝtß River. But so also, it seemed, had half of the million tourists

who swarm to Iceland each summer! Viewing platforms gave direct vista over the Hraunfossar

(meaning literally Lava Waterfalls), a series of cascades almost 1 km in

length, where surface water and melt-water draining from Langj÷kull percolate

down through the Hallmundarhraun lava field to emerge from under the leading

edge of the deep surface layer of lava, tumbling down in cascades over the

moss-covered series of bed-rock steps into the passing HvÝtß River (see above

left) (Photo 3 - Hraunfossar cascading from under lava field). The bright turquoise cascades pouring

turquoise cascades pouring

out from under the lava contrasted in colour with the

murky grey glacial silt-laden river. The Hallmundarhraun resulted from a

volcanic eruption under the NW edge of Langj÷kull around 930 AD, the time of the

first recorded Settlement of Iceland, which flowed westwards along

valleys to form a massive lava field covering an area of some 242 square kms

bordering on the HvÝtß River. The Hraunfossar made a unique sight with the long

lateral series of cascades pouring from under the base of the depth of lava

which overlays the lower strata of harder, more impervious bed-rock bordering the river's far bank (Photo 4 - Hraunfossar). out from under the lava contrasted in colour with the

murky grey glacial silt-laden river. The Hallmundarhraun resulted from a

volcanic eruption under the NW edge of Langj÷kull around 930 AD, the time of the

first recorded Settlement of Iceland, which flowed westwards along

valleys to form a massive lava field covering an area of some 242 square kms

bordering on the HvÝtß River. The Hraunfossar made a unique sight with the long

lateral series of cascades pouring from under the base of the depth of lava

which overlays the lower strata of harder, more impervious bed-rock bordering the river's far bank (Photo 4 - Hraunfossar).

Paths led along to another set of falls on the

river's main course, where the fast-flowing, silt-laden glacial river has carved

out a deep, winding canyon in the lava (see below right). Barnafoss (meaning Children's Falls)

takes its name from 2 children from a nearby farm who drowned here while

crossing a natural rock-bridge above the falls. Barnafoss drops into the winding

lava canyon in a series of falls (see left) (Photo 5 - Barnafoss Falls) where the power of the water has cut

rock-bridge arches under which the surging torrent now flows in the base of the

falls. A platform gave perfect views upstream along the length of the canyon of

grey-black

lava to the falls (Photo

6 - Barnafoss), and a footbridge spanning the river gorge crossed onto the

lava field on the far side for further downstream views along the silt-grey HvÝtß and the

length of Hraunfossar cascading from from under the lava field

(see above right) (Photo

7 - Downstream view of Hraunfossar). Clambering up onto

the lava gave an astonishing vista of the full extent of the Hallmundarhraun

lava field stretching away into the distance, covered with Woolly Hair Moss and birch

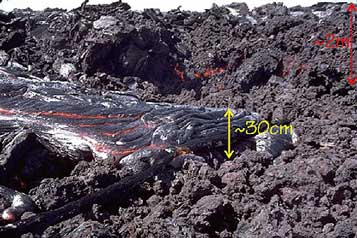

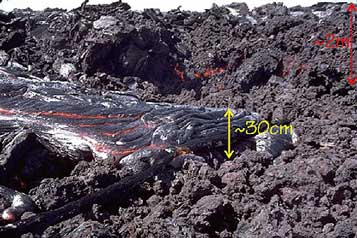

scrub. The bright sunlight lit beautiful patches of Pahoe-hoe basaltic lava flow,

picking out the pronounced detailed patterning of the lava's smooth, undulating, ropy

surface texture (Photo

8 - Pahoe-hoe lava-flow) (see left). Pahoe-hoe lava-flows are associated

with low-effusion rate eruptions; the low flow-velocity of Pahoe-hoe lava's advance means that the skin

formed by air-cooling is not disrupted during flow and can therefore maintain its smooth,

unbroken, well-insulating surface. This contrasts with the other major type of

basaltic lava-flow, given the Hawaiian name of A'a. A'a lava-flows are

characterised by their rough, knobbly surface composed of

fragments of clinker-rubble, formed as

pasty lava is pulled apart by shearing and twisting during A'a lava's

rapid advance, as distinct from Pahoe-hoe

lava-flow's smooth, ropy surface texture (Photo

9 - Ropy textured Pahoe-hoe). The basaltic chemical composition of

the 2 types of lava (Pahoe-hoe and A'a) is the same; the difference in their

physical form reflects different lava-flow dynamics (see below right). under the lava field

(see above right) (Photo

7 - Downstream view of Hraunfossar). Clambering up onto

the lava gave an astonishing vista of the full extent of the Hallmundarhraun

lava field stretching away into the distance, covered with Woolly Hair Moss and birch

scrub. The bright sunlight lit beautiful patches of Pahoe-hoe basaltic lava flow,

picking out the pronounced detailed patterning of the lava's smooth, undulating, ropy

surface texture (Photo

8 - Pahoe-hoe lava-flow) (see left). Pahoe-hoe lava-flows are associated

with low-effusion rate eruptions; the low flow-velocity of Pahoe-hoe lava's advance means that the skin

formed by air-cooling is not disrupted during flow and can therefore maintain its smooth,

unbroken, well-insulating surface. This contrasts with the other major type of

basaltic lava-flow, given the Hawaiian name of A'a. A'a lava-flows are

characterised by their rough, knobbly surface composed of

fragments of clinker-rubble, formed as

pasty lava is pulled apart by shearing and twisting during A'a lava's

rapid advance, as distinct from Pahoe-hoe

lava-flow's smooth, ropy surface texture (Photo

9 - Ropy textured Pahoe-hoe). The basaltic chemical composition of

the 2 types of lava (Pahoe-hoe and A'a) is the same; the difference in their

physical form reflects different lava-flow dynamics (see below right).

A wild camp in Upper Borgarfj÷rur:

we still needed to find somewhere acceptable to camp tonight; it was out of the

question to consider returning to Varmaland to camp. We therefore continued

further into Upper Borgarfj÷rur valley to investigate potential wild camp spots

(click

here for detailed map of route), documented for us by fellow travellers

Kathy and Rick Howe from California (read the Howes'

excellent  Travelin' Tortuga Icelandic travelogues on their web site

Icelandic Sagas

and

Land of the Sideways Sun).

A couple of kms eastwards beyond Barnafoss, a rough gravelly area of lava was

just about accessible from the road but was also very open and exposed. We

therefore continued for a further 5kms to H˙safell Camping, but this was both

obscenely expensive and even more overcrowded with Icelandic holiday-makers than

Varmaland; even its web site publicity photographs were enough to repel! We Travelin' Tortuga Icelandic travelogues on their web site

Icelandic Sagas

and

Land of the Sideways Sun).

A couple of kms eastwards beyond Barnafoss, a rough gravelly area of lava was

just about accessible from the road but was also very open and exposed. We

therefore continued for a further 5kms to H˙safell Camping, but this was both

obscenely expensive and even more overcrowded with Icelandic holiday-makers than

Varmaland; even its web site publicity photographs were enough to repel! We

moved on, still with no where identified to camp tonight. Our guide books

suggested Fljˇtstunga Farm offered camping, located in remote wild country 6kms

beyond the end of the tarmaced Route 518, on a single-track dirt road across the

Hallmundarhraun lava field on the far side of the upper HvÝtß River. The remote

VÝgelmir lava cave and Surtshellir lava tube were both on Fljˇtstunga Farm's

property, and the farm organised tours of the caves. We set off, and just beyond

H˙safell where Route 518 passed through an area of birch scrub, we chanced upon a

lay-by, sheltered from the road by birch woodland; here was a potential wild

camp spot if all else failed. Just beyond, we reached the road junction where

the tarmac ended and Route 550 mountain road branched off southwards across the

remote interior towards Thingvellir. moved on, still with no where identified to camp tonight. Our guide books

suggested Fljˇtstunga Farm offered camping, located in remote wild country 6kms

beyond the end of the tarmaced Route 518, on a single-track dirt road across the

Hallmundarhraun lava field on the far side of the upper HvÝtß River. The remote

VÝgelmir lava cave and Surtshellir lava tube were both on Fljˇtstunga Farm's

property, and the farm organised tours of the caves. We set off, and just beyond

H˙safell where Route 518 passed through an area of birch scrub, we chanced upon a

lay-by, sheltered from the road by birch woodland; here was a potential wild

camp spot if all else failed. Just beyond, we reached the road junction where

the tarmac ended and Route 550 mountain road branched off southwards across the

remote interior towards Thingvellir.

Route 518 continued ahead as a single-track dirt

road crossing the upper reaches of the grey silt-laden HvÝtß, which here flowed

in shallow, winding meanders across the lava wilderness of Geitlandshraun with

the imposing snow-white mountainous massif of Langj÷kull filling the eastern

horizon

(Photo

10 - HvÝtß River, Geitlandsrhaun lava field and Langj÷kull) (see above

left). Even in bright afternoon sunlight, it was a fearfully staggering vista.

The dirt road crossed the dusty lava wasteland, running alongside an

ochre-coloured scoria ridge (see left), and on the far side climbed

steeply to cross the

ridge; this descended even more steeply of the far side into a further desolate

valley filled with the moss-covered Hallmundarhraun lava field. The rough road

turned to cross a tributary of the HvÝtß, cutting across the lava field to reach

the turning to Fljˇtstunga Farm up on the hill-side. It was a remote and

isolated spot, but heart-sink: the camping symbol on Fljˇtstunga's sign was

crossed out. We tried unsuccessfully to phone, but the number was no longer in

use. We drove up, to be met by a security man who said we were 2 years too late;

the place had changed hands and no longer offered accommodation or camping! steeply to cross the

ridge; this descended even more steeply of the far side into a further desolate

valley filled with the moss-covered Hallmundarhraun lava field. The rough road

turned to cross a tributary of the HvÝtß, cutting across the lava field to reach

the turning to Fljˇtstunga Farm up on the hill-side. It was a remote and

isolated spot, but heart-sink: the camping symbol on Fljˇtstunga's sign was

crossed out. We tried unsuccessfully to phone, but the number was no longer in

use. We drove up, to be met by a security man who said we were 2 years too late;

the place had changed hands and no longer offered accommodation or camping!

Disappointed, we returned across the lava field

and over the ridge down to the bleak HvÝtß valley, pausing to photograph the

magnificent view looking up to Langj÷kull. Back to the junction with Route 550,

we returned along the tarmac lane and turned into the birch-wooded lay-by as our

wild camp spot for tonight. Largely hidden from the lane and the occasional

passing traffic, with plenty of cover from the dense birch woods, we set up camp

(see below left) (Photo

11 - Upper Borgarfj÷rur Wild camp) and lit the barbecue for supper (see right). Despite failing to find camping out at Fljˇtstunga, the drive out there had given opportunity to explore the wilds of

the upper HvÝtß valley with its views of Langj÷kull and the extensive reaches of

the Hallmundarhraun and Geitlandshraun lava fields. Despite fears of being disturbed by

late-arriving tourist cars pulling into the lay-by, we slept through

without

disturbance, and woke to a cloudier, cooler morning. without

disturbance, and woke to a cloudier, cooler morning.

The lower Borgarfj÷rur valley to Borgarnes:

as we returned down the valley, Hraunfossar and Barnafoss were already swarming

with tourists. Beyond Reykholt, we turned off on the more southerly Route 53

across broad open farming country of the lower HvÝtß and its meandering

tributary, the GrÝmsß, towards Borgarnes (click

here for detailed map of route). The southern aspect of the valley was

dominated by the shapely, craggy peaks of Hafnarfjall and Hrossatunga, outlying

crests of the Skarsheii range (see right). The road ran alongside these peaks to approach

the junction of the Ring Road (see below left). In busy traffic coming up from ReykjavÝk, we

crossed the 3kms wide bridge over the open mouth of Borgarfj÷rur, where the now

brisk NE wind was whipping up vicious looking turbulence. A modern commercial

centre now sprawled along the Ring Road at the outskirts of Borgarnes, with

filling stations, supermarkets, tourist-oriented consumer shops and banks. We

pulled in here and stocked up with 4 days' provisions and used the ATM for cash.

Having come this morning from the peaceful remoteness of the Upper HvÝtßdalur

valley down to this modern world materialism, it felt as if we had suddenly been

pitched into a different universe!

A blustery day in camp at Snorrastair:

thankful to be leaving all this behind, we headed north on the Ring Road in

heavy traffic, and even more thankfully turned off onto Route 54 towards SnŠfellsnes

(click

here for detailed map of route). In a A blustery day in camp at Snorrastair:

thankful to be leaving all this behind, we headed north on the Ring Road in

heavy traffic, and even more thankfully turned off onto Route 54 towards SnŠfellsnes

(click

here for detailed map of route). In a couple of kms, we reached the tiny

hamlet of Borg ß Mřrum, and paused at the tiny church by the historic farm where

the father of Egil Skallagrimsson, hero of Egil's Saga, had first settled and

which Snorri Sturluson later acquired by marriage. We continued across the rough

pasture land which was criss-crossed with basalt outcrops and distant volcanic

peaks, and beyond the ┴lftßrhraun lava field, eventually reached the turning to

Snorrastair Farm, the first of tonight's campsite options. 2 kms along the

farm's driveway, the little campsite looked empty and inviting. This was the

start-point for the walk across the Eldborgarhraun lava field to climb the scoria

cone of the Eldborg Crater. We had been undecided between the campsite at

Snorrastair Farm and our other option at the Eldborg Hotel a little further

north which was a Camping Card site. We phoned Eldborg for more information; the

person answering assured us it was not busy, but it was another of those sites

with showers at the neighbouring swimming pool charged extra at an expensive

700kr. The lady at the farmhouse confirmed the Snorrastair price was 2,500kr

all-inclusive of showers, kitchen and wi-fi. That decided it; we should stay

here at Snorrastair Farm. couple of kms, we reached the tiny

hamlet of Borg ß Mřrum, and paused at the tiny church by the historic farm where

the father of Egil Skallagrimsson, hero of Egil's Saga, had first settled and

which Snorri Sturluson later acquired by marriage. We continued across the rough

pasture land which was criss-crossed with basalt outcrops and distant volcanic

peaks, and beyond the ┴lftßrhraun lava field, eventually reached the turning to

Snorrastair Farm, the first of tonight's campsite options. 2 kms along the

farm's driveway, the little campsite looked empty and inviting. This was the

start-point for the walk across the Eldborgarhraun lava field to climb the scoria

cone of the Eldborg Crater. We had been undecided between the campsite at

Snorrastair Farm and our other option at the Eldborg Hotel a little further

north which was a Camping Card site. We phoned Eldborg for more information; the

person answering assured us it was not busy, but it was another of those sites

with showers at the neighbouring swimming pool charged extra at an expensive

700kr. The lady at the farmhouse confirmed the Snorrastair price was 2,500kr

all-inclusive of showers, kitchen and wi-fi. That decided it; we should stay

here at Snorrastair Farm.

Even inland at H˙safell this morning, the wind

had increased, and

at Borgarnes it was whipping up a swell on the fjord; but out

here on the high, flat coastal plain exposed to the full force of winds blowing

straight off the North Atlantic, a 10 m/s gale was forcefully blowing from the

NE. There was absolutely no shelter or wind-break on the open, flat turfed

camping area, and the old barn converted for facilities served to give no

shelter from the gale blowing from the NE. With some difficulty struggling

against the force of the wind, we pitched with George faced into the gale (see

right) (Photo

12 - Snorrastair Farm-Camping), and

once inside out of the wind, the sun was warm. Quite remarkably,

we initially had the campsite almost to ourselves, but as we prepared supper, more

arrivals began, all clustering around us trying to shelter from the wind.

Clearly these inexperienced tourists in hire cars had no idea of checking wind

direction before trying to pitch their tents; they simply would not believe our

attempts to demonstrate that the wind direction was from the NE, and that trying

to huddle around the facilities barn would offer no shelter. Why not pitch your

tent in the lee of your car, we suggested. But no. Eventually giving up the

struggle against the force of the NE gale, they moved on! Late in the evening,

the sun declined to the NW, giving us chance for at Borgarnes it was whipping up a swell on the fjord; but out

here on the high, flat coastal plain exposed to the full force of winds blowing

straight off the North Atlantic, a 10 m/s gale was forcefully blowing from the

NE. There was absolutely no shelter or wind-break on the open, flat turfed

camping area, and the old barn converted for facilities served to give no

shelter from the gale blowing from the NE. With some difficulty struggling

against the force of the wind, we pitched with George faced into the gale (see

right) (Photo

12 - Snorrastair Farm-Camping), and

once inside out of the wind, the sun was warm. Quite remarkably,

we initially had the campsite almost to ourselves, but as we prepared supper, more

arrivals began, all clustering around us trying to shelter from the wind.

Clearly these inexperienced tourists in hire cars had no idea of checking wind

direction before trying to pitch their tents; they simply would not believe our

attempts to demonstrate that the wind direction was from the NE, and that trying

to huddle around the facilities barn would offer no shelter. Why not pitch your

tent in the lee of your car, we suggested. But no. Eventually giving up the

struggle against the force of the NE gale, they moved on! Late in the evening,

the sun declined to the NW, giving us chance for

some glorious late sun

photographs against the silhouetted peaks of SnŠfellsnes

(Photo

13 - SnŠfellsnes sunset) (see below left and right). We battened down for a

rough night of blustery wind. some glorious late sun

photographs against the silhouetted peaks of SnŠfellsnes

(Photo

13 - SnŠfellsnes sunset) (see below left and right). We battened down for a

rough night of blustery wind.

It was indeed a rough night, and this morning

dawned heavily overcast with a brisk NE wind still blowing at 10 m/s. The

forecast confirmed the decision to take a day in camp here today, and to climb

the Eldborg Carter tomorrow when the wind speed would be less. The weather

remained largely overcast all day and the gusting NE wind scarcely lessoned. Snorrastair had proved a good choice of campsite for a rest day, with its full

facilities, albeit straightforward, particularly the welcome relief of showers

which were becoming something of a rarity! The site-wide wi-fi was also a

welcome addition, and with its very reasonable all-inclusive price, Snorrastair

merited a +4 rating. It was indeed a rough night, and this morning

dawned heavily overcast with a brisk NE wind still blowing at 10 m/s. The

forecast confirmed the decision to take a day in camp here today, and to climb

the Eldborg Carter tomorrow when the wind speed would be less. The weather

remained largely overcast all day and the gusting NE wind scarcely lessoned. Snorrastair had proved a good choice of campsite for a rest day, with its full

facilities, albeit straightforward, particularly the welcome relief of showers

which were becoming something of a rarity! The site-wide wi-fi was also a

welcome addition, and with its very reasonable all-inclusive price, Snorrastair

merited a +4 rating.

The Eldborg scoria cone crater: the

gales continued all night, buffeting George, with no let up now forecast for

today's walk across Eldborgarhraun lava field and climb of the Eldborg (meaning

Fire Castle) scoria cone crater. The walk began on a clear path following

the Kaldß River past the home pastures of Snorrastair Farm, to reach the edge

of Eldborgarhraun lava field.

This covers an area of some 32 square kms and had

spread from eruptions some 5,000~8,000 years ago from a short SW~NE fissure. The Eldborg scoria spatter cone, exceptionally symmetrical in shape, formed during

an eruption from a circular vent

along the fissure that had caused the lava field. Regular crater walls built up

around the vent in thin layers of lava, forming a narrow edge all around the

conical scoria crater, which now This covers an area of some 32 square kms and had

spread from eruptions some 5,000~8,000 years ago from a short SW~NE fissure. The Eldborg scoria spatter cone, exceptionally symmetrical in shape, formed during

an eruption from a circular vent

along the fissure that had caused the lava field. Regular crater walls built up

around the vent in thin layers of lava, forming a narrow edge all around the

conical scoria crater, which now stands 60m above the surrounding lava field,

slightly oval in shape, 200m in diameter and 50m deep inside. stands 60m above the surrounding lava field,

slightly oval in shape, 200m in diameter and 50m deep inside.

The path turned way from the river and threaded

a way through the dense and otherwise impenetrable birch scrub vegetation

which now covers the lava field, with a ground cover of Bilberry, Crowberry and

Bearberry. The birch scrub stood head height, meaning that the cone crater only

occasionally came into view as the path rose across higher areas of lava (see

left). The

path wound a way for some 3kms through this maze of impenetrable birch scrub,

reaching a mini-crater slightly apart from the older main Eldborg crater, and

built up of scoria clinker rubble. This was the site of a second and younger,

smaller and perhaps more explosive eruption resulting in A'a lava, the other

major type of basaltic lava-flow. There was now a clear view ahead of the main

Eldborg crater, the walls of which looked formidably vertical, rising 60m above

the surrounding birch scrub-covered lava. But we could make out a clear path

rising diagonally across the near walls, and figures standing on the crater rim

way above (see above left)

(Photo

14 - Eldborg Crater). The path now passed the mini-crater, and climbed steps cut into

the

lava to cross a less distinct subsidiary crater where ropy patterned Pahoe-hoe

lava-flows were more evident (Photo

15 - Pahoe-hoe lava flow) (see above right). The wind was now blowing more strongly, at times

making it difficult to maintain balance. We had been well-sheltered crossing the

main lava field among the birch scrub. the

lava to cross a less distinct subsidiary crater where ropy patterned Pahoe-hoe

lava-flows were more evident (Photo

15 - Pahoe-hoe lava flow) (see above right). The wind was now blowing more strongly, at times

making it difficult to maintain balance. We had been well-sheltered crossing the

main lava field among the birch scrub.

We now reached the foot of the main crater

wall. Steps cut into the lava helped to climb the lower part, then a safety

chain gave some security to haul up the much steeper higher sections. The

sharply angular projections of lava gave good footing, but the main path was

warm smooth by the 100s who daily scale this route up to the crater's rim (Photo

16 - Climbing Eldborg Crater) (see left). With

the aid of the safety chain, we scrambled a way up to emerge onto the crater

rim, no more than 2 m wide, to stand gazing down into the deep abyss of the

crater whose inner walls dropped sheer into its depths (Photo

17 - Crater rim) (see right). The jagged, brittle

summit wall around Eldborg's 200m diameter oval crater rim were now sealed off

as a safety measure, but the distant views across the crater's lava walls

looking over nearer mountains towards the

peak of SnŠfellsnes crowned by its glacier were simply magnificent (see below

left) (Photo

18 - SnŠfellsnes glacier). We stood now alone taking our photographs

across the gulf of the crater with its lava walls (see left)

Photo 19 - Eldborg Crater rim),

then

gingerly

began the steep descent, thankful for the security of the safety chain.

Edging our way down, we reached the foot of what had felt the near-vertical cone

wall, here able to stand to admire the view looking down over the subsidiary crater

below and the separate mini-crater set further over (see below right) (Photo

20 - Subsidiary craters). began the steep descent, thankful for the security of the safety chain.

Edging our way down, we reached the foot of what had felt the near-vertical cone

wall, here able to stand to admire the view looking down over the subsidiary crater

below and the separate mini-crater set further over (see below right) (Photo

20 - Subsidiary craters).

Back across the side of the scoria subsidiary crater

down to a paths junction, we cut across on a side-path and up the slope of

scoria clinkers making up the smaller cone. This provided a vividly marked

contrast between the slow-moving Pahoe-hoe lava-flows that had accumulated

around the eruption and had built up to create Eldborg's cone; while here at the

separate and later mini-crater, the cone was formed of loose, small pieces of

rubble and airy, light pumice clinker, associated with classic A'a lava-flow. We climbed

the slope to the crater rim for the views looking back across the subsidiary crater to

the main Eldborg cone (Photo

21 - A'a lava) (see below right). Regaining the main path, we began the long return walk

through the birch scrub-covered Eldborgarhraun lava field (see below left), which at least gave

some shelter from the wind that had increased in intensity. Back at George, the

wind made it difficult to open the doors without risk of slamming. We settled up

with the farmer's wife and asked about the lava field; it was part of Snorrastair's

land, where the farm had bore holes for geothermal hot water, but the scrub-

Back across the side of the scoria subsidiary crater

down to a paths junction, we cut across on a side-path and up the slope of

scoria clinkers making up the smaller cone. This provided a vividly marked

contrast between the slow-moving Pahoe-hoe lava-flows that had accumulated

around the eruption and had built up to create Eldborg's cone; while here at the

separate and later mini-crater, the cone was formed of loose, small pieces of

rubble and airy, light pumice clinker, associated with classic A'a lava-flow. We climbed

the slope to the crater rim for the views looking back across the subsidiary crater to

the main Eldborg cone (Photo

21 - A'a lava) (see below right). Regaining the main path, we began the long return walk

through the birch scrub-covered Eldborgarhraun lava field (see below left), which at least gave

some shelter from the wind that had increased in intensity. Back at George, the

wind made it difficult to open the doors without risk of slamming. We settled up

with the farmer's wife and asked about the lava field; it was part of Snorrastair's

land, where the farm had bore holes for geothermal hot water, but the scrub- land

had no other use than for grazing sheep. land

had no other use than for grazing sheep.

The

expensive and mediocre Eldborg Hotel

Camping: after 2 nights at

the well-appointed and good value Snorrastair farm-camping, we now drove 25kms

north for a night at Eldborg Hotel Camping (click

here for detailed map of route). We knew this had no showers, (at

least we were not

prepared to pay 700kr each for showers at their swimming

pool), its only advantage being that it accepted payment by Camping Card. The

now powerful headwind made driving around Route 54 unsteady, yet even so the

irresponsible young tourists in hire-cars still hassled from behind and sped past

dangerously in the face of oncoming traffic. We turned off along Eldborg's

driveway across the flat moorland, to reach the unsightly, ugly concrete bunker

of a hotel. The rough, grassy camping field alongside was thankfully almost

empty, and in the now really strong NE gale blowing over from the inland

mountains, the thick spruce and birch hedge across the middle of the field at

least provided an effective wind-break. A German couple in a camping-car filling

the middle space had no objection to our pitching alongside in the lee of the

only section of hedge within reach of the one and only power socket; with some

difficulty battling against the gale, we settled in (see below right). prepared to pay 700kr each for showers at their swimming

pool), its only advantage being that it accepted payment by Camping Card. The

now powerful headwind made driving around Route 54 unsteady, yet even so the

irresponsible young tourists in hire-cars still hassled from behind and sped past

dangerously in the face of oncoming traffic. We turned off along Eldborg's

driveway across the flat moorland, to reach the unsightly, ugly concrete bunker

of a hotel. The rough, grassy camping field alongside was thankfully almost

empty, and in the now really strong NE gale blowing over from the inland

mountains, the thick spruce and birch hedge across the middle of the field at

least provided an effective wind-break. A German couple in a camping-car filling

the middle space had no objection to our pitching alongside in the lee of the

only section of hedge within reach of the one and only power socket; with some

difficulty battling against the gale, we settled in (see below right).

We walked over to the huge concrete bunker

masquerading as a hotel to book in, to be treated to an utterly indifferent and

unresponsive non-welcome from the girl at the hotel reception; if such a Why

should I bother to serve you? attitude represented the standard of service

expected of such a hotel, it spoke volumes about the place! We insisted on her

showing us the camping facilities, limited to 2 WCs and a hand basin in a dingy,

underground dungeon beneath the hotel, along with a wash-up sink and electric

ring We walked over to the huge concrete bunker

masquerading as a hotel to book in, to be treated to an utterly indifferent and

unresponsive non-welcome from the girl at the hotel reception; if such a Why

should I bother to serve you? attitude represented the standard of service

expected of such a hotel, it spoke volumes about the place! We insisted on her

showing us the camping facilities, limited to 2 WCs and a hand basin in a dingy,

underground dungeon beneath the hotel, along with a wash-up sink and electric

ring passing for a 'kitchen'. For all this substandard service and mediocre

facilities, they had the nerve to charge 1,200kr/person plus 1,000kr for

electricity (showers in their swimming pool were 700kr each extra). We paid by

Camping card. When it came later to writing up Eldborg Hotel's review, we tried

telephoning the hotel and received a similarly inhospitable, non-responsive

response! The place was given a generous -2 rating. passing for a 'kitchen'. For all this substandard service and mediocre

facilities, they had the nerve to charge 1,200kr/person plus 1,000kr for

electricity (showers in their swimming pool were 700kr each extra). We paid by

Camping card. When it came later to writing up Eldborg Hotel's review, we tried

telephoning the hotel and received a similarly inhospitable, non-responsive

response! The place was given a generous -2 rating.

The wind continued unabated, blowing violently

if you stepped beyond the shelter of the hedge; tucked in behind the wind-break,

George was snug as we cooked supper. The following morning, with the wind still

forecast as 7 m/s today, we decided to take a rest day here in spite of the

place's inadequacies, and review things tomorrow. The neighbouring camping-car

departed and we moved George fully into the shelter of the spruce hedge. This

morning we discovered that the campsite's basement WCs were in a disgustingly

filthy state. At reception we demanded to know from the hotel staff if this was

the normal

standard offered in the hotel, and if not, why were campers

discriminated against. The girl hastily set to cleaning the loos, emptying bins

and re-filling paper towel and loo-roll holders. The gale continued to blow all

day, but the forecast showed a gradual reduction tomorrow and return to a more

gentle 3 m/s on Tuesday. standard offered in the hotel, and if not, why were campers

discriminated against. The girl hastily set to cleaning the loos, emptying bins

and re-filling paper towel and loo-roll holders. The gale continued to blow all

day, but the forecast showed a gradual reduction tomorrow and return to a more

gentle 3 m/s on Tuesday.

Geruberg Basalt Columns: the following morning was bright,

and

as forecast the wind had reduced to 5 m/s. We returned to the main Route 54 and

almost opposite, a farm drive dirt track led inland sign-posted for Geruberg and

Rauamelur. The trackway led in a short distance to the Geruberg Basalt Columns, a

2kms long shattered escarpment of grey, 50m tall, hexagonal and square columns

with a skirt of broken blocks at the foot of the cliffs, the longest and most

perfect set of such basalt pillars in the country (see left). We stopped at a parking area

and climbed up the slope to the foot of the huge columns which towered overhead.

But the natural grandeur of this wonderful feat of nature was tarnished by the

silly antics of crowds of tourists swarming all over the cliffs and the skyline

above the pillars. For such folk, the only passing relevance of this

magnificent natural phenomenon was to form an incidental backdrop for their

'selfies'. But fortunately, true to form, the tourists' span of attention

typically was so brief that within moments, they had all rushed off in their

hire-cars to sully the next 'attraction', leaving us in Geruberg Basalt Columns: the following morning was bright,

and

as forecast the wind had reduced to 5 m/s. We returned to the main Route 54 and

almost opposite, a farm drive dirt track led inland sign-posted for Geruberg and

Rauamelur. The trackway led in a short distance to the Geruberg Basalt Columns, a

2kms long shattered escarpment of grey, 50m tall, hexagonal and square columns

with a skirt of broken blocks at the foot of the cliffs, the longest and most

perfect set of such basalt pillars in the country (see left). We stopped at a parking area

and climbed up the slope to the foot of the huge columns which towered overhead.

But the natural grandeur of this wonderful feat of nature was tarnished by the

silly antics of crowds of tourists swarming all over the cliffs and the skyline

above the pillars. For such folk, the only passing relevance of this

magnificent natural phenomenon was to form an incidental backdrop for their

'selfies'. But fortunately, true to form, the tourists' span of attention

typically was so brief that within moments, they had all rushed off in their

hire-cars to sully the next 'attraction', leaving us in

peace to admire in wonder the Geruberg Basalt Columns. We stood amid the Bilberry and Crowberry

(see below right) at the foot of the parade of columns, admiring their majesty,

and contemplating their formation as the cooling basaltic lava cracked into

such regular patterns on such a scale. From this perspective, we took our photos

in the clear morning sunshine looking along the line of the columnar cliff

escarpment; some of the pillars were even leaning outwards, separated from the

walls of the cliffs

peace to admire in wonder the Geruberg Basalt Columns. We stood amid the Bilberry and Crowberry

(see below right) at the foot of the parade of columns, admiring their majesty,

and contemplating their formation as the cooling basaltic lava cracked into

such regular patterns on such a scale. From this perspective, we took our photos

in the clear morning sunshine looking along the line of the columnar cliff

escarpment; some of the pillars were even leaning outwards, separated from the

walls of the cliffs (see above

right) (Photo

22 - Geruberg Basalt Columns). This

was nature at its most spectacular here at Geruberg. A further km along the

trackway, brought us to the abandoned farm of Ytri-Rauamelur, and its little

corrugated metal chapel standing on a slope surrounded by a hedge of birches

(see left).

From here we could look back along the Geruberg escarpment stretching away into

the distance.

(see above

right) (Photo

22 - Geruberg Basalt Columns). This

was nature at its most spectacular here at Geruberg. A further km along the

trackway, brought us to the abandoned farm of Ytri-Rauamelur, and its little

corrugated metal chapel standing on a slope surrounded by a hedge of birches

(see left).

From here we could look back along the Geruberg escarpment stretching away into

the distance.

The Harbour Seal colony at YtrÝ-Tunga beach: re-joining the main Route

54 (click

here for detailed map of route), we turned westwards across the green

coastal strip, passing modern working farms set against the backdrop of

elegantly sculpted corries of mighty Hafursfell towering above. The road swung

inland away from the coast but running parallel with the mountainous spine of

the SnŠfellsnes peninsula which was now dominated by the grey peaks of

Ljˇsufj÷ll. The now wide and remarkably flat, green coastal farming plain

stretched away to the distant coast and inland to the spine of mountains which

culminated in the

peak of SnŠfellsnes capped with its glacier (see left). At the Vegamˇt service station road junction, Route 56 branched off to Stykkishˇlmur on

the peninsula's north coast; Route 54 continued westwards turning back towards

the coast. Here we turned off down to YtrÝ-Tunga beach, but so regrettably had

the tourist hordes. Our reason for venturing off the main road down to this

beautiful stretch of wild beaches and golden sands surrounded by rounded

volcanic boulders, was to culminated in the

peak of SnŠfellsnes capped with its glacier (see left). At the Vegamˇt service station road junction, Route 56 branched off to Stykkishˇlmur on

the peninsula's north coast; Route 54 continued westwards turning back towards

the coast. Here we turned off down to YtrÝ-Tunga beach, but so regrettably had

the tourist hordes. Our reason for venturing off the main road down to this

beautiful stretch of wild beaches and golden sands surrounded by rounded

volcanic boulders, was to find the colony of Harbour Seals that bask on the

rocks along this coast-line. On such a bright, sunny day, we were not sure

whether the seals would be out of the water. But as we walked along the

magnificent beach, and scrambled over the rocks at the far end, sure enough

there were 2 pairs of Harbour Seals basking by the water's edge on flat rocks

(see right) (Photo

23 - Harbour Seals at YtrÝ Tunga).

Much smaller than Grey Seals, Harbour Seals are the most common seal species in

Icelandic waters, and can be recognised by their shorter, be-whiskered 'teddy

bear' snouts. They live on fish and are accomplished divers, feeding at depths

of 30~50m. They are sociable animals, gathering in groups to bask on the

shore-line. We positioned ourselves for photographs of the seals, as they lay

basking unconcernedly on the rocks no more than 5~10m from us (Photo

24 - Basking Harbour Seal); for our Seals Photo Gallery, click on

Harbour Seals of YtrÝ-Tunga.

But the peace of the setting was shattered by the arrival of a whole busload of tourists making an

unbelievable racket. Not surprisingly the find the colony of Harbour Seals that bask on the

rocks along this coast-line. On such a bright, sunny day, we were not sure

whether the seals would be out of the water. But as we walked along the

magnificent beach, and scrambled over the rocks at the far end, sure enough

there were 2 pairs of Harbour Seals basking by the water's edge on flat rocks

(see right) (Photo

23 - Harbour Seals at YtrÝ Tunga).

Much smaller than Grey Seals, Harbour Seals are the most common seal species in

Icelandic waters, and can be recognised by their shorter, be-whiskered 'teddy

bear' snouts. They live on fish and are accomplished divers, feeding at depths

of 30~50m. They are sociable animals, gathering in groups to bask on the

shore-line. We positioned ourselves for photographs of the seals, as they lay

basking unconcernedly on the rocks no more than 5~10m from us (Photo

24 - Basking Harbour Seal); for our Seals Photo Gallery, click on

Harbour Seals of YtrÝ-Tunga.

But the peace of the setting was shattered by the arrival of a whole busload of tourists making an

unbelievable racket. Not surprisingly the

seals flopped over into the water and

swam off, their shiny black heads just visible in the water (Photo

25- Swimming seal). Why such folk come

here remains a mystery: they clearly have no interest in or appreciation of the

natural surroundings and wild-life, and with all their noise and disturbance,

they ruin whatever it is they do come to see. That regrettably is the story of

modern Iceland, whose unique natural beauty is progressively being destroyed by

the get-rich-quick greed of the mass tourism seals flopped over into the water and

swam off, their shiny black heads just visible in the water (Photo

25- Swimming seal). Why such folk come

here remains a mystery: they clearly have no interest in or appreciation of the

natural surroundings and wild-life, and with all their noise and disturbance,

they ruin whatever it is they do come to see. That regrettably is the story of

modern Iceland, whose unique natural beauty is progressively being destroyed by

the get-rich-quick greed of the mass tourism industry. industry.

We walked slowly back over the rocks, to photograph the distant

snow-capped peak of SnŠfellsnes against the foreground of shore-side Marram

Grass

(see left) (Photo

26 - SnŠfellsnes peak from YtrÝ Tunga), as ignorant, ill-mannered tourists, too self-obsessed even to show any

awareness of others, wandered blithely in front of our cameras. Further along,

we stood quietly by a side beach photographing Dunlins (see right) (Photo

27 - Dunlin) and Ringed Plovers

busily pecking away at the water's edge, as tourists wandered indifferently past.

B˙ir church and the B˙arhaun lava field: back to

the main road, we continued westwards in bright afternoon sunshine (click

here for detailed map of route). The road

over the flat, wide coastal strip ran alongside the wonderfully sculpted

mountainous escarpment of the SnŠfellsnes spine, with watercourses cascading

over the brim of cliffs and sunlight picking out all the details of the crags. A

further 20kms along around B˙avÝk Bay, we reached the point where the partly unsurfaced Route 54

branched off over a pass on the mountainous spine to ËlafsvÝk; just B˙ir church and the B˙arhaun lava field: back to

the main road, we continued westwards in bright afternoon sunshine (click

here for detailed map of route). The road

over the flat, wide coastal strip ran alongside the wonderfully sculpted

mountainous escarpment of the SnŠfellsnes spine, with watercourses cascading

over the brim of cliffs and sunlight picking out all the details of the crags. A

further 20kms along around B˙avÝk Bay, we reached the point where the partly unsurfaced Route 54

branched off over a pass on the mountainous spine to ËlafsvÝk; just beyond a turning led down to the former fishing and trading hamlet of B˙ir. The

trading settlement was abandoned in the early 19th century, and all that remains now is

the tiny wooden church and nearby isolated inn-hotel, standing at the edge of the B˙ahraun lava field. B˙ir's

original name was Hraunh÷fn, meaning Lava-field Harbour.

beyond a turning led down to the former fishing and trading hamlet of B˙ir. The

trading settlement was abandoned in the early 19th century, and all that remains now is

the tiny wooden church and nearby isolated inn-hotel, standing at the edge of the B˙ahraun lava field. B˙ir's

original name was Hraunh÷fn, meaning Lava-field Harbour.

We turned off onto the single-track lane which led across the lava field,

past the hotel, and ended at the tiny, black-tarred wooden B˙ir church (see

left). The

present church is a reconstruction of the original 1703 church. More impressive

than the simple little church was the turf-topped lava-block wall surrounding

the graveyard. But again, the tourist hordes had got here before us, wandering

aimlessly around the church; they were even clambering pointlessly onto the

turf-topped wall. Having taken our photos of

the church, we moved George back to

park near the hotel so that we could walk back along the lane to admire the lava

field, backed by the glorious view of the SnŠfellsnes peak and glacier (see

right) (Photo

28 - SnŠfellsnes above B˙ahraun), and B˙ir church

alongside the lava field (see below right). The B˙ahraun

lava field had flowed originally from the nearby B˙arklettur crater, and now forms a low area of wonderfully shaped

lava formations and fissures, all covered

with vegetation and moss (Photo

29 - B˙ahraun fissures) (see left). A little further back from the coast by a prominent

fissure (see below left), we found a small patch of the church, we moved George back to

park near the hotel so that we could walk back along the lane to admire the lava

field, backed by the glorious view of the SnŠfellsnes peak and glacier (see

right) (Photo

28 - SnŠfellsnes above B˙ahraun), and B˙ir church

alongside the lava field (see below right). The B˙ahraun

lava field had flowed originally from the nearby B˙arklettur crater, and now forms a low area of wonderfully shaped

lava formations and fissures, all covered

with vegetation and moss (Photo

29 - B˙ahraun fissures) (see left). A little further back from the coast by a prominent

fissure (see below left), we found a small patch of

Autumn Gentians

(Gentianella amarella) still

largely in bud

(Photo 30 -

Autumn Gentian)

(see below left). We also noted a flat area just off the road as a possible wild

camp spot with beautiful Grass of Parnassus growing in profusion among the lava

boulders (see below right). Autumn Gentians

(Gentianella amarella) still

largely in bud

(Photo 30 -

Autumn Gentian)