|

CAMPING

IN SWEDEN 2013 - the capital city Stockholm, Sweden's oldest town Sigtuna, the

royal and religious cult-centre of Gamla Uppsala, and the university-city of Uppsala: CAMPING

IN SWEDEN 2013 - the capital city Stockholm, Sweden's oldest town Sigtuna, the

royal and religious cult-centre of Gamla Uppsala, and the university-city of Uppsala:

A peaceful campsite by the Färnebofjärden

National Park:

we headed south-west from Gävle, turning off onto a minor road past Gysinge Bruk,

a former iron foundry dating from the 17th century and now the Naturum for the

Färnebofjärden National Park. Just beyond we reached the village of Österfärnebo

where a lane led along an esker ridge down through the lakeland of

Färnebofjärden, and a short distance along reached Färnebofjärdens Camping set

delightfully along the lake-shore

(Photo 1 - Lakeside camping in Färnebofjärden National Park). Here we were greeted with enthusiastic

hospitality by the Swiss owners who had recently taken over the campsite, and

gladly settled in on the lake shore as formations of Canada Geese swooped low

over the lake's still waters with the late afternoon sun just dipping behind the

pines which covered the narrowing esker. This small site set among the Färnebofjärden lakeland was wonderfully peaceful after all the noise-ridden

holiday-camps of the Bothnian coast. The evening grew dusky but stayed warm, and

for the first time in a number of weeks we sat out late with candles twinkling

on our supper table.

|

Click on the 3 highlighted areas of

the map

for details of

the Stockholm city region |

|

The north~south divide of the Dalälven

river: another familiar connection for us, as we

learnt from the campsite owner, is that the Dalälven river which flows lazily

through the Färnebofjärden lake system is in fact the lower continuation of the

Österdalsälven on whose banks we had camped at Idre, and which flows through

Lake Siljan on to here. The lower Dalälven broadens out into a network of

lakes and meres connected by short stretches of fast-flowing rapids, weaving

across a mosaic of riverside fens, meadows and ancient forests. During the

spring melts, flood plains spread across the flat landscape. The river had

originally flowed into the Mälaran lakes at Stockholm, but when this course was

blocked by glacial moraine, the Dalälven found a new course north-eastwards to

empty into the Baltic near to Gävle. The jagged Färnebofjärden lake system

shore-line encloses more than 2,000 islands, and the landscape of the Dalälven

now forms a natural boundary line between the boreal coniferous trees of the north and

Southern Sweden's broad leafed tree species such as

oak, beech and alder - what the Swedish botanist Carl von Linné called the Limes Norrlandicus (Northlands boundary). It also marks

something of a cultural divide between the north and south of the country. The north~south divide of the Dalälven

river: another familiar connection for us, as we

learnt from the campsite owner, is that the Dalälven river which flows lazily

through the Färnebofjärden lake system is in fact the lower continuation of the

Österdalsälven on whose banks we had camped at Idre, and which flows through

Lake Siljan on to here. The lower Dalälven broadens out into a network of

lakes and meres connected by short stretches of fast-flowing rapids, weaving

across a mosaic of riverside fens, meadows and ancient forests. During the

spring melts, flood plains spread across the flat landscape. The river had

originally flowed into the Mälaran lakes at Stockholm, but when this course was

blocked by glacial moraine, the Dalälven found a new course north-eastwards to

empty into the Baltic near to Gävle. The jagged Färnebofjärden lake system

shore-line encloses more than 2,000 islands, and the landscape of the Dalälven

now forms a natural boundary line between the boreal coniferous trees of the north and

Southern Sweden's broad leafed tree species such as

oak, beech and alder - what the Swedish botanist Carl von Linné called the Limes Norrlandicus (Northlands boundary). It also marks

something of a cultural divide between the north and south of the country.

A day's walking in Färnebofjärden lakeland: Gysinge Bruk

iron works had developed

here in the 17th century taking advantage of the local coincidence of Färnebofjärden's

3 natural features, fast-flowing water to provide power, local iron ore and

plentiful timber supplies for charcoal. After visiting the remains of the Bruk, we spent an interesting day walking out

along the esker-ridge which connected a series of islands projecting southwards

from the campsite into Lake Färnebofjärden. Here we were able to see

direct evidence of this transition landscape supporting a mixture of both

northern and southern plant life. The steep-sided ridge sloping down to the lake

was covered with dark northern pines, but growing among them were small oak and

alder trees, and alongside the typical northern forest ground-cover of bilberry

and lingonberry were patches of southern Lily of the Valley, the plants now well

past flowering but not yet reached the orange berry stage. Our stay at Färnebofjärdens

Camping was a peaceful prelude to the capital city where we should move

tomorrow. A day's walking in Färnebofjärden lakeland: Gysinge Bruk

iron works had developed

here in the 17th century taking advantage of the local coincidence of Färnebofjärden's

3 natural features, fast-flowing water to provide power, local iron ore and

plentiful timber supplies for charcoal. After visiting the remains of the Bruk, we spent an interesting day walking out

along the esker-ridge which connected a series of islands projecting southwards

from the campsite into Lake Färnebofjärden. Here we were able to see

direct evidence of this transition landscape supporting a mixture of both

northern and southern plant life. The steep-sided ridge sloping down to the lake

was covered with dark northern pines, but growing among them were small oak and

alder trees, and alongside the typical northern forest ground-cover of bilberry

and lingonberry were patches of southern Lily of the Valley, the plants now well

past flowering but not yet reached the orange berry stage. Our stay at Färnebofjärdens

Camping was a peaceful prelude to the capital city where we should move

tomorrow.

Into Stockholm, the Swedish capital, and a

wretchedly overcrowded campsite: crossing

the Dalälven from Färnebofjärden and Gysinge, Route 56 took us south

initially through pine woods but increasingly through agricultural countryside

to reach the small town of Heby for a provisions stock-up at the local ICA

supermarket. South from here on Route 254, harvesting of golden ripe fields of barley

and oats was in full swing. Route 70, another cross-country road used earlier

in the trip north from Mora to Idre, today led us SE to join the E18 motorway

which became busier as we approached the NW outskirts of Stockholm. Guided by

our satnav we followed Route 275 through residential areas, eventually turning

off to reach Ängby Camping. It had taken us just 2½ hours to journey from

peaceful rural lakeside solitude to over-crowded, over-priced city congestion.

Ängby Camping already looked overfull, but we pulled in to be greeted in curtly

perfunctory manner. If we had thought the rest of Southern Sweden was expensive,

clearly Stockholmers have made an art form out of rip-off prices: the overnight

stay cost a whopping 335kr totally exploiting the unending tourist demand, and

caravans and camping cars were shoe-horned like sardines into postage

stamp-sized pitches. We had chosen Ängby Camping as being more conveniently

sited than the alternative Stockholm camping option, Bredäng Camping on the

southern side of the city (even more expensive), and having easy Metro access

into the city centre. But it was easily the most miserably wretched and

exploitatively overpriced campsite in Sweden; we had our space for our visit to

the capital, such as it was, but would have to take out another mortgage to pay

for it! But the most fearful issue was the overcrowding: the Swedish Fire and

Rescue Agency and the Swedish Camping Association publish campsite fire safety

standards specifying minimum intervening distance between pitches. We are making

a formal request for the Stockholm Fire Authority to investigate whether, with

open barbecues in regular usage immediately next to neighbouring caravans, Ängby

Camping's severely confined pitches satisfy recommended fire safety standards.

Our first day in Stockholm: it

poured with rain all night and this morning the waterlogged pitches and traffic

noise made the overcrowding even more miserable. And despite the extortionate

prices, facilities at Ängby Camping were the worst of the entire trip: showers

and toilets were cramped, old-fashioned and grubby and the limited number meant

inevitable queues; the kitchen was poorly equipped and limited wash-ups sinks

again meant queuing. With the weather still gloomily overcast, we set off for

the 800m walk to the Ängbyplan Metro station. Stockholm's Metro system, the

Tunnel-bana (T-bana) provides a fast and efficient means of public transport

around the city (see left); single tickets are expensive (like everything else in

Stockholm) costing 32kr but last for an hour covering both T-bana and buses

(Photo 2 - Stockholm's Metro, the Tunnel-bana). We

followed the journey into the centre on the map noting the pronunciation of

station names as they were announced, and amid the crowds got off at T-Centralen,

a bewildering station complex covering a vast area and with multiple exits. The

first challenge was identifying our location when we emerged feeling even more

disorientated Our first day in Stockholm: it

poured with rain all night and this morning the waterlogged pitches and traffic

noise made the overcrowding even more miserable. And despite the extortionate

prices, facilities at Ängby Camping were the worst of the entire trip: showers

and toilets were cramped, old-fashioned and grubby and the limited number meant

inevitable queues; the kitchen was poorly equipped and limited wash-ups sinks

again meant queuing. With the weather still gloomily overcast, we set off for

the 800m walk to the Ängbyplan Metro station. Stockholm's Metro system, the

Tunnel-bana (T-bana) provides a fast and efficient means of public transport

around the city (see left); single tickets are expensive (like everything else in

Stockholm) costing 32kr but last for an hour covering both T-bana and buses

(Photo 2 - Stockholm's Metro, the Tunnel-bana). We

followed the journey into the centre on the map noting the pronunciation of

station names as they were announced, and amid the crowds got off at T-Centralen,

a bewildering station complex covering a vast area and with multiple exits. The

first challenge was identifying our location when we emerged feeling even more

disorientated than normally on arrival at a new capital city. Crowds, traffic,

road works and absence of street names left us totally bemused. We struggled to

find a way through unidentified back streets to Drottning-gatan, a narrow and

pedestrianised street crowded with tourists and lined with the tackiest of tat

shops, thoroughly unattractive. We headed towards the Riksbron and parliament

building to emerge by the narrow channel of Norrström, part of Lake Mälaren,

which separates Riddarholmen, the large island now covered by the buildings of

Stockholm's Old Town, Gamla Stan than normally on arrival at a new capital city. Crowds, traffic,

road works and absence of street names left us totally bemused. We struggled to

find a way through unidentified back streets to Drottning-gatan, a narrow and

pedestrianised street crowded with tourists and lined with the tackiest of tat

shops, thoroughly unattractive. We headed towards the Riksbron and parliament

building to emerge by the narrow channel of Norrström, part of Lake Mälaren,

which separates Riddarholmen, the large island now covered by the buildings of

Stockholm's Old Town, Gamla Stan

Stockholm's history: Stockholm had

been founded here on the island of Riddarholmen in 1255 as a fortification to

secure the original city of Sigtuna from maritime attack. The settlement

developed through trade with other cities of the Hanseatic League, and German

merchants set up business here gaining Stockholm its predominant position over

Sigtuna which it soon eclipsed by the 14~15th centuries. Following the break-up

of the Kalmar Union and Gustav Vasa's capture of Stockholm and establishment of

an independent Swedish kingdom in 1523, royal power was established in the city

making it the capital of

what would become one of Europe's major powers under

King Gustav II Adolfus in the 17th century. Military defeat by Imperial Russia

in the 18th century Great Northern Wars brought an end to Swedish territorial

expansion in Northern and Eastern Europe, and Stockholm developed politically

and culturally as capital of a smaller Swedish state. During the 19th century it

was still little more than a rural town, becoming overcrowded and lacking all the features of urban life

like piped water supply and drainage. Sweden's neutrality

during WW2 meant the city escaped the bomb damage suffered by other European

capitals, and the post-war Social-Democratic domination in Swedish politics

brought a sustained programme of modernisation. Here we stood by the water's

edge of Lake Mälaren which pervades every corner of the city, still bemused by

the inevitable crowds of tourists in mid-August. what would become one of Europe's major powers under

King Gustav II Adolfus in the 17th century. Military defeat by Imperial Russia

in the 18th century Great Northern Wars brought an end to Swedish territorial

expansion in Northern and Eastern Europe, and Stockholm developed politically

and culturally as capital of a smaller Swedish state. During the 19th century it

was still little more than a rural town, becoming overcrowded and lacking all the features of urban life

like piped water supply and drainage. Sweden's neutrality

during WW2 meant the city escaped the bomb damage suffered by other European

capitals, and the post-war Social-Democratic domination in Swedish politics

brought a sustained programme of modernisation. Here we stood by the water's

edge of Lake Mälaren which pervades every corner of the city, still bemused by

the inevitable crowds of tourists in mid-August.

Changing of the Guards at the Royal Palace:

we hurried across under the archway linking the parliament building's 2 wings,

following the crowds up the steps into the courtyard of Tessin the Younger's

Royal Palace; the Changing of the Guards which takes place daily at

12-15 was clearly a popular tourist attraction. Officious young soldiers in

their comic-opera dress uniforms were marshalling the crowds behind cordons

around the edge of the square, and we managed to find positions with something

of a view but with little idea of what was to happen. More of these most

unmilitary looking young soldiers pranced around, some brimming with

self-importance, others clearly feeling self-conscious in front of the crowds.

An announcement over the PA, partly in English, detailed the history of the

Swedish Life Guards formed by Gustav Vasa as a royal protection squad, although

the present generation of guards looked incapable of defending even a child's toy

fort! Eventually a troop of cavalry trotted around led by mounted musicians who

played a selection of musical comedy airs while other soldiers hidden by the

crowds marched around. It was all a bit twee, lacking much of the dignity of the

equivalent British spectacle, but the tourists loved it and the Japanese

photographed one another in front of it all as the horses trotted around

distributing horse dung with military precision

(Photo 3 - Changing the Guards at Stockholm's Royal Palace).

We extricated ourselves to get

back for the next parliamentary visit. We extricated ourselves to get

back for the next parliamentary visit.

Visit

to the Riksdag (Swedish Parliament): Group 4

clearly has a very lucrative security contract with the Riksdag administration

since their guards on the entrance to the Parliament building were changed at

least 3 times while we queued for admission; it was first come, first served,

and the next 28 visitors joined the hour-long tour. Eventually we were admitted

and posses of Group 4 security staff subjected us to the usual emptying of

pockets rigmarole. The guide, speaking in fluent English, led us up to the

plenary chamber's hallway from where we could look down over the panorama of Lake Mälaren and Stockholm City Hall

(Photo 4 - Panorama over Lake Mälaren and Stockholm City Hall). Before taking us into the visitors' gallery she gave a background history of

Sweden's parliamentary system. Until constitutional changes in 1971, the Riksdag had

been bi-cameral with one chamber elected by popular ballot, the other by more

selective political groups. The 2 chambers met in the East Wing of the

parliamentary building built in 1905. With the change to unicameral system, a

new and larger chamber was needed: the oval-shaped West Wing formerly occupied

by the national bank was taken over and a new upper storey added in the 1970s to

create the oval-shaped modern plenary chamber where we now gathered. Visit

to the Riksdag (Swedish Parliament): Group 4

clearly has a very lucrative security contract with the Riksdag administration

since their guards on the entrance to the Parliament building were changed at

least 3 times while we queued for admission; it was first come, first served,

and the next 28 visitors joined the hour-long tour. Eventually we were admitted

and posses of Group 4 security staff subjected us to the usual emptying of

pockets rigmarole. The guide, speaking in fluent English, led us up to the

plenary chamber's hallway from where we could look down over the panorama of Lake Mälaren and Stockholm City Hall

(Photo 4 - Panorama over Lake Mälaren and Stockholm City Hall). Before taking us into the visitors' gallery she gave a background history of

Sweden's parliamentary system. Until constitutional changes in 1971, the Riksdag had

been bi-cameral with one chamber elected by popular ballot, the other by more

selective political groups. The 2 chambers met in the East Wing of the

parliamentary building built in 1905. With the change to unicameral system, a

new and larger chamber was needed: the oval-shaped West Wing formerly occupied

by the national bank was taken over and a new upper storey added in the 1970s to

create the oval-shaped modern plenary chamber where we now gathered.

The Swedish Riksdag

has 349 members elected by proportional representation for a 4 year term from

the country's 29 constituencies which correspond with the counties. In the last

general election of 2010, 84% of the 7 million Swedes on the national electoral

role voted. With the constitutional threshold of 4% of votes cast to qualify for

party status and receive state funding, there are currently 8 political parties

in the Riksdag. To stand as an MP, candidates must be adopted by one of the

recognised parties. The present government is formed by a centre-right coalition

made up of the leading Moderate Party (107 seats), Liberal Party (24 seats),

Centre Party (23 seats) and Christian Democrats (19 seats) making a total of 173

seats, 2 short of an absolute majority. The Opposition is made up of the Social

Democratic Party (112 seats), Green Party (25 seats) and Left Party (19 seats),

a total of 156 seats. The balance of power however is held by a new party formed

in 2010, the Sweden Democrats, with 20 seats who entered Parliament on a ticket

of reducing immigration, an understandable thorny topical issue in Swedish

politics looking around Stockholm or any Swedish town or city today. The Prime

Minister is elected by MPs from

the majority party, the current PM (since 2006)

being Frederik Reinfeldt leader of the Moderate Party (see right). Parliament is chaired by

the Speaker, who is also elected by MPs from their number; the current office

holder is Per Westerberg. In October each year, the King, currently Carl XVI

Gustaf, as Head of State officially opens the new parliament, and the PM

announces the government's programme for the coming year. Much of the work of

preparing parliamentary business and refining bills is conducted by the 15 standing

committees. the majority party, the current PM (since 2006)

being Frederik Reinfeldt leader of the Moderate Party (see right). Parliament is chaired by

the Speaker, who is also elected by MPs from their number; the current office

holder is Per Westerberg. In October each year, the King, currently Carl XVI

Gustaf, as Head of State officially opens the new parliament, and the PM

announces the government's programme for the coming year. Much of the work of

preparing parliamentary business and refining bills is conducted by the 15 standing

committees.

From the visitors' gallery, we looked down into the oval parliamentary chamber

where MPs sit grouped not by political party but by constituency

(see left) (Photo 5 - Plenary chamber of the Swedish Parliament, the Riksdag). From there we

were led across the bridge link to the West Wing to see the twin chambers

previously used by the pre-1971 bi-cameral parliament and now used as meeting

rooms by the 2 largest parties. On the return walk to the security entrance, we

paused by the portraits of the leaders of the 4 Estates (Nobility, Clergy,

Burghers and Peasantry) who in 1809 had agreed to offer the Swedish throne to

Napoleon's Marshall, Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte who became King Karl XIV Johan,

founder of the Bernadotte dynasty, the current royal family. This had been

another educative parliamentary visit to supplement our list of European

parliaments visited during our travels, and to add further to our understanding

of our present host-country's society. What had impressed us most was the

unbelievable level of Swedish political participation (84% turnout in the 2010

general election) compared with UK's sad indifference towards its governance.

The island of Riddarholmen and the Riddarholms-kyrkan: we had

decided to devote our first day in the capital to the Gamla Stan (Old Town) area

of the city spread across the central islands of Stadsholmen, Helgeandsholmen

and Riddarholmen. Leaving the parliament we crossed the bridge firstly to the

neighbouring island of Riddarholmen to find the Riddarholms-kyrkan. This ancient

foundation, originally a Franciscan monastery until the 1525 Reformation, has

for centuries been the royal burial church for Swedish monarchs starting with

Magnus Ladulås in 1290 whose sarcophagus stood in the chancel. The church's

inner walls were lined with the coats of arms of the Swedish Seraphim

knightly order. Leading noble families had their sepulchral chapels around the

nave, but of greater interest were the royal dynastic burial chapels: the

Carolean monarchs, the huge sarcophagus of Gustav II Adolfus with smaller tombs

of his family

(Photo 6 - Sarcophagus of King Gustav II Adolfus), down in the crypt the tombs of Gustav III and his family, and in

a side chapel the large sarcophagus of Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte (Karl XIV Johan)

along with tombs of his family (see right). As we walked around, we struggled to recall the

historical significance of all those buried in this royal pantheon of

Swedish monarchs. Despite the still murkily overcast sky, Riddarholmen's outer

quay gave a panoramic view across the width of Lake Mälaren to Stockholm's

city hall, its slender tower topped by the Swedish crest of 3 gilded crowns.

Stockholm's Gamla Stan (Old Town): re-crossing to Stadsholmen, we walked up through the

narrow streets of the Old Town to Stockholm's cathedral, Storkyrkan set on the

highest point of the island and crammed in among other old buildings. Built

in 1279, it is now the royal church where traditionally Swedish monarchs have

been crowned and married. The narrow street of Trångsund was lined with shops

selling the tackiest of tourist ephemera and thronged with hoards of mindless

tourists among whom mingled some very suspicious-looking characters suggesting

this was prime territory for pickpockets. This led to the more pleasant sloping

open space of Stortorget, one side of which was lined with the Baroque building

of the Nobel Museum, the others with crowded street cafés

(Photo 7 - Stortorget in Gamla Stan). This square had been

the scene of the Danish King Christian II's massacre of Swedish nobility in

1520, known as the 'Stockholm Bloodbath', before he himself was booted out along

with the rest of the Danes by Gustav Vasa's successful Swedish coup in 1623. We

continued along Trångsund, eyeing uneasily the dodgy characters hovering among

the crowds of tourists, to reach the Tyska kyrkan. Built originally for

Stockholm's medieval German merchants, the church had received the usual

extravaganza of Baroque embellishment in the 18th century. On to Järntorget we paused for ice creams

(see left),

before walking down to the quay at Slussen to investigate

ferries across Lake Mälaren to Djurgården for tomorrow. Stockholm's Gamla Stan (Old Town): re-crossing to Stadsholmen, we walked up through the

narrow streets of the Old Town to Stockholm's cathedral, Storkyrkan set on the

highest point of the island and crammed in among other old buildings. Built

in 1279, it is now the royal church where traditionally Swedish monarchs have

been crowned and married. The narrow street of Trångsund was lined with shops

selling the tackiest of tourist ephemera and thronged with hoards of mindless

tourists among whom mingled some very suspicious-looking characters suggesting

this was prime territory for pickpockets. This led to the more pleasant sloping

open space of Stortorget, one side of which was lined with the Baroque building

of the Nobel Museum, the others with crowded street cafés

(Photo 7 - Stortorget in Gamla Stan). This square had been

the scene of the Danish King Christian II's massacre of Swedish nobility in

1520, known as the 'Stockholm Bloodbath', before he himself was booted out along

with the rest of the Danes by Gustav Vasa's successful Swedish coup in 1623. We

continued along Trångsund, eyeing uneasily the dodgy characters hovering among

the crowds of tourists, to reach the Tyska kyrkan. Built originally for

Stockholm's medieval German merchants, the church had received the usual

extravaganza of Baroque embellishment in the 18th century. On to Järntorget we paused for ice creams

(see left),

before walking down to the quay at Slussen to investigate

ferries across Lake Mälaren to Djurgården for tomorrow.

With the sky at last beginning to brighten, we walked along the waterfront past

moored ferries and over-priced quay-side restaurants. With glances up at the

buildings of Gamla Stan crowded onto Stadsholmen's crest, we continued along

towards Slottsbacken which was lined with Tessin's featureless four-square

Royal Palace with Storkyrkan at the crest of the hill. The 2 arms of the Royal

Palace's east wing enclosing gardens stretched down towards the waters of Lake Mälaren.

Tessin had designed his Palace in simple, uniform style to replace the former

Tre Kronor castle which had burnt down during Karl XII's reign at the beginning

of the 18th century. At the top of the steps at the level of the palace gardens,

a blue-uniformed young soldier stood guarding one of the royal flower pots;

after performing a couple of comical prances for the benefit of his sergeant who

came on a tour of inspection, he settled back into his sentry box (see right). At the corner

of the palace, a gushing fountain poured down into a basin looking for all the

world as if someone had just flushed one of the royal loos. The sun at last

broke through lighting the views along towards Gamla Stan

(Photo 8 - Looking towards Gamla Stan from the Royal Palace)

and over the bridge to the Opera House across the

water (Photo 9 - City panorama across Norrström and Strömbron). We crossed to the lawned gardens of the Riksdaghuset, its east façade now

in deep shade, but from under the trees we were able to photograph the now

well-lit Royal Palace (Photo 10 - Royal Palace built by Tessin the Younger in 1754). With the sky at last beginning to brighten, we walked along the waterfront past

moored ferries and over-priced quay-side restaurants. With glances up at the

buildings of Gamla Stan crowded onto Stadsholmen's crest, we continued along

towards Slottsbacken which was lined with Tessin's featureless four-square

Royal Palace with Storkyrkan at the crest of the hill. The 2 arms of the Royal

Palace's east wing enclosing gardens stretched down towards the waters of Lake Mälaren.

Tessin had designed his Palace in simple, uniform style to replace the former

Tre Kronor castle which had burnt down during Karl XII's reign at the beginning

of the 18th century. At the top of the steps at the level of the palace gardens,

a blue-uniformed young soldier stood guarding one of the royal flower pots;

after performing a couple of comical prances for the benefit of his sergeant who

came on a tour of inspection, he settled back into his sentry box (see right). At the corner

of the palace, a gushing fountain poured down into a basin looking for all the

world as if someone had just flushed one of the royal loos. The sun at last

broke through lighting the views along towards Gamla Stan

(Photo 8 - Looking towards Gamla Stan from the Royal Palace)

and over the bridge to the Opera House across the

water (Photo 9 - City panorama across Norrström and Strömbron). We crossed to the lawned gardens of the Riksdaghuset, its east façade now

in deep shade, but from under the trees we were able to photograph the now

well-lit Royal Palace (Photo 10 - Royal Palace built by Tessin the Younger in 1754).

Crossing the bridge to Gustav

Adolfs Torg where fisherman lined the water's edge casting their lines for

salmon in the murky waters flowing along the Norrström channel, there were

splendid views of the Riksdag's East Wing now well-lit by the late afternoon

sun (Photo 11 - East wing of the Riksdag). Back at our day's starting point at Riksbron we were able to photograph the

parliament's West Wing curving façade with the modern parliamentary chamber's

upper storey extension visited earlier. Crossing the Vasabron, there was a

perfect panorama across Lake Mälaren of the entire Riksdag and government

offices lit by the western sun (see left) (Photo 12 - Panorama of the Swedish Parliament Buildings). On the southern side of the bridge we passed the

magnificent 17th century Baroque building of the Riddarhuset in whose Great Hall

the Nobility Estate had met to govern the country before the 1865 constitutional reforms abolished the 4 Estates in favour of a bi-cameral parliament on European

lines (Photo 13 - 17th century Baroque Riddarhuset). Negotiating a way along the pedestrian-unfriendly Centralbron, we

eventually reached the uncharacteristically grubby Gamla Stan T-bana station, to catch our #18 Metro on the Hässelby Strand line back out to the campsite.

Our first day in Stockholm had been a rewarding one with our visit to the

Parliament, but despite the city's attractive watery environment and

grandiose buildings, Gamla Stan had a distinctly unsafe feel with an

ever-present sense of pickpockets loitering among the crowds of tourists;

perhaps it's a sign of the times we now live in. Crossing the bridge to Gustav

Adolfs Torg where fisherman lined the water's edge casting their lines for

salmon in the murky waters flowing along the Norrström channel, there were

splendid views of the Riksdag's East Wing now well-lit by the late afternoon

sun (Photo 11 - East wing of the Riksdag). Back at our day's starting point at Riksbron we were able to photograph the

parliament's West Wing curving façade with the modern parliamentary chamber's

upper storey extension visited earlier. Crossing the Vasabron, there was a

perfect panorama across Lake Mälaren of the entire Riksdag and government

offices lit by the western sun (see left) (Photo 12 - Panorama of the Swedish Parliament Buildings). On the southern side of the bridge we passed the

magnificent 17th century Baroque building of the Riddarhuset in whose Great Hall

the Nobility Estate had met to govern the country before the 1865 constitutional reforms abolished the 4 Estates in favour of a bi-cameral parliament on European

lines (Photo 13 - 17th century Baroque Riddarhuset). Negotiating a way along the pedestrian-unfriendly Centralbron, we

eventually reached the uncharacteristically grubby Gamla Stan T-bana station, to catch our #18 Metro on the Hässelby Strand line back out to the campsite.

Our first day in Stockholm had been a rewarding one with our visit to the

Parliament, but despite the city's attractive watery environment and

grandiose buildings, Gamla Stan had a distinctly unsafe feel with an

ever-present sense of pickpockets loitering among the crowds of tourists;

perhaps it's a sign of the times we now live in.

Day 2 of our visit to Stockholm - ferry across the harbour to Djurgården to

visit the Vasa Museum: with the sky clearer this morning and

sun shining through the trees, we made our way back over to the Ängbyplan Metro

station. The train was busier on a Saturday morning and we continued 2 further

stops beyond T-Centralen down to Slussen. Emerging from the station, we crossed

the bridge to the southern end of Gamla Stan, glancing up to the wedge of old

buildings and church spires covering Stadsholmen. Our plan was to spend today on

the island of Djurgården, crossing by ferry from Slussen to visit the Museum

devoted to the preserved 17th century royal warship, the Vasa. On

reaching the ferry terminal, it was clear from the long queues that many others,

both tourists and locals, were also heading across to Djurgården most likely to

visit the outdoor museum of Skansen or the Tivoli fairground at Gröna Lunds; there

would be a long wait for the ferry. Pensioners' tickets were available reduced

from 45kr to 30kr, a good price for such a popular journey, and in fact the

queue moved quickly as boat followed boat across the harbour. We were soon

aboard and stood at the forward end for photos of the magnificent panorama of

Gamla Stan as the ferry chugged across the

waters of Lake Mälaren (see right) (Photo 14 - Panorama of Gamla Stan from Djurgården ferry). We did not realise it at the time, but the ferry passed

close to the spot where the warship Vasa had sunk in 1628 just off the

island of Beckholmen. As the ferry drew into the Tivoli dock on Djurgården, we

could hear the screams of fairground visitors being hurtled around on the

roller coasters towering overhead. We followed the quay around and ahead could

see the curious outline of the museum building specially constructed on the site

of a former naval dockyard to house the preserved wooden warship Vasa

with mast-heads seemingly projecting through the roof. Day 2 of our visit to Stockholm - ferry across the harbour to Djurgården to

visit the Vasa Museum: with the sky clearer this morning and

sun shining through the trees, we made our way back over to the Ängbyplan Metro

station. The train was busier on a Saturday morning and we continued 2 further

stops beyond T-Centralen down to Slussen. Emerging from the station, we crossed

the bridge to the southern end of Gamla Stan, glancing up to the wedge of old

buildings and church spires covering Stadsholmen. Our plan was to spend today on

the island of Djurgården, crossing by ferry from Slussen to visit the Museum

devoted to the preserved 17th century royal warship, the Vasa. On

reaching the ferry terminal, it was clear from the long queues that many others,

both tourists and locals, were also heading across to Djurgården most likely to

visit the outdoor museum of Skansen or the Tivoli fairground at Gröna Lunds; there

would be a long wait for the ferry. Pensioners' tickets were available reduced

from 45kr to 30kr, a good price for such a popular journey, and in fact the

queue moved quickly as boat followed boat across the harbour. We were soon

aboard and stood at the forward end for photos of the magnificent panorama of

Gamla Stan as the ferry chugged across the

waters of Lake Mälaren (see right) (Photo 14 - Panorama of Gamla Stan from Djurgården ferry). We did not realise it at the time, but the ferry passed

close to the spot where the warship Vasa had sunk in 1628 just off the

island of Beckholmen. As the ferry drew into the Tivoli dock on Djurgården, we

could hear the screams of fairground visitors being hurtled around on the

roller coasters towering overhead. We followed the quay around and ahead could

see the curious outline of the museum building specially constructed on the site

of a former naval dockyard to house the preserved wooden warship Vasa

with mast-heads seemingly projecting through the roof.

The 1628 sinking of the Vasa

in Stockholm harbour: The Vasa had been constructed on the

orders of King Gustav II Adolfus who, in the arms race with Sweden's arch-enemy

the Danes, wanted the most powerful warship afloat with 72 heavy guns. Vasa

was therefore built to royal specification as the Royal Ship, Sweden's foremost

naval vessel of the day, in the Skeppsgården navy yards by the Dutch

shipwright Henryk Hybertson. 1,000 oak trees were selected for timber for the

huge ship's construction which took 3 years. In early August 1628, the new ship

was ready for her maiden voyage, moored just below the Royal Castle in the

centre of Stockholm, and loaded with ballast, guns and ammunition. Gustav II

Adolfus was as usual away in Prussia fighting with the Poles, and was impatient

to have his new warship join his forces. On Sunday 10 August 1628, crowds lined

the quays to witness the sailing of the Swedish navy's prestigious new warship.

On board were just over 100 of the ship's normal full crew of 300 along with

members of their families who were given permission to join the first part of the

maiden voyage down the archipelago. The occasion of great pomp and ceremony was

described with vivid accuracy by the Danish ambassador in a letter to his

government describing Sweden's new mightily armed warship. The 1628 sinking of the Vasa

in Stockholm harbour: The Vasa had been constructed on the

orders of King Gustav II Adolfus who, in the arms race with Sweden's arch-enemy

the Danes, wanted the most powerful warship afloat with 72 heavy guns. Vasa

was therefore built to royal specification as the Royal Ship, Sweden's foremost

naval vessel of the day, in the Skeppsgården navy yards by the Dutch

shipwright Henryk Hybertson. 1,000 oak trees were selected for timber for the

huge ship's construction which took 3 years. In early August 1628, the new ship

was ready for her maiden voyage, moored just below the Royal Castle in the

centre of Stockholm, and loaded with ballast, guns and ammunition. Gustav II

Adolfus was as usual away in Prussia fighting with the Poles, and was impatient

to have his new warship join his forces. On Sunday 10 August 1628, crowds lined

the quays to witness the sailing of the Swedish navy's prestigious new warship.

On board were just over 100 of the ship's normal full crew of 300 along with

members of their families who were given permission to join the first part of the

maiden voyage down the archipelago. The occasion of great pomp and ceremony was

described with vivid accuracy by the Danish ambassador in a letter to his

government describing Sweden's new mightily armed warship.

Stability tests were conducted

with 30 men running back and forth across the deck while the ship was moored at

the quay, but after 3 runs the test was stopped because the ship listed badly;

suspicion was already rife about Vasa's stability. The captain however

ordered the ship to be kedged out into the main channel; 4 of the ship's sails

were set, the guns fired, and Vasa moved forward across the harbour under

her own power. But she had not advanced more than 1,300m when a sudden gust of

wind from the SW caught her; she keeled over with water rushing into her still

open gun ports, and the mighty warship slowly sank to the bottom of the harbour

in 32m of water, drowning around 50 of those on board. News of the disaster

reached the King 2 weeks later; he wrote to the Council of the Realm that

'imprudence or negligence must have been the cause', and demanded that the guilty

parties must be punished. It was a total embarrassment for all from the King

downwards; he had said that 'second to God, the welfare of the Kingdom depends

on its Navy', and the Vasa with its mighty armaments was built to his own

specifications. Sweden had already lost several warships in the period 1624~28

both to storms and to enemy action and the Vasa was essential to maintain

Sweden's naval supremacy in the Baltic.

Two theories accounting for the

loss were examined by the court of enquiry: 1) the weight of the improperly

secured guns rolling back caused the listing 2) the

crew were drunk and failed in their duties. But the Captain, Dutch-born Söfring

Hansson, swore that the guns had been secured, and he

blamed its design and construction for ship's instability. The crew also were questioned and swore that

the ballast was loaded; it was Sunday and they had been to church having had

nothing to drink. They also asserted that the ship was unstable: the keel was

too small in relation to the size, height and top-heavy weight of the vessel.

The original ship-builder had died the previous year, but his successor Hein Jakobsson and the shipyard master Arent de Groot, both experienced Dutch

shipwrights, insisted that work had been carried out to the specifications and

dimensions commissioned by the King himself. Whose fault was it then? demanded

the interrogator; only God knows, answered de Groot. Both the King and God were

considered infallible, and no guilty party was ever identified or punished.

Gustav II Adolfus was killed 4 years later in 1632 at the Battle of Lützen and

the matter of the cause of Vasa's sinking was quietly allowed to be

forgotten.

In modern retrospect, who was to

blame? partly the Admiral for allowing the ship to sail after the uncertain

stability tests, but he was facing Gustav's impatience to have his new warship

delivered; partly the King who had insisted on this specification of size and

heavy armaments; partly the ship-builder, but he already had a sound record of

building successful warships and the Vasa was well-constructed and

differed from other ships of the day only in size and heavy armaments. 17th

century ships were constructed not to drawings but empirically from the

shipwright's experience. The issue was that the Vasa was conceived as

simply too big and too heavily armed, and therefore too top heavy for the

designs of the day; she was a maritime disaster just waiting to happen.

Immediate attempts were made to

salvage the Vasa but these failed. In the 1660s her heavy cannons were

recovered; they each weighed over a ton and using only the air supply in a

primitive diving bell, hooks were attached to each cannon and 50 were lifted. It

was a remarkable achievement. The wreck of the Vasa was abandoned and

remained forgotten in 32m of mud and water, but in 1956 an experienced salvage

engineer, Anders Franzén located the ship. Divers working in the murky depths

secured steel cables under the wreck and in 1961, she was lifted by a salvaging

company. The Vasa re-appeared on the surface of Stockholm harbour 333

years after her sinking with the world's press and TV to witness this incredible

event. The ship's timbers, which had been protected against rot by the Baltic's

low salinity, were treated with polyethylene glycol and the jigsaw puzzle of

recovered pieces reassembled, so that 95% of the preserved wreck is original.

After the wreck was raised, diving operations continued investigating the seabed

around the wreck site, and many of the Vasa's carved wooden sculptures

were also recovered along with her wooden gun carriages from which the cannon

had been lifted. The conserved warship is now displayed in a specially designed

museum so that the Vasa can now be seen in her full glory (Photo 15 -

Specially-built museum for the warship Vasa); with her full

masts, she would have towered over 50m (164 feet) high. Visit the

Vasa Museum web site

Our visit to Vasa Museum: we queued and paid what seemed an

expensive admission of 130kr each, and entered the dimly lit hall: there ahead

stood the Vasa, an utterly staggering sight

(Photo 16 - the conserved warship Vasa). Having viewed the film

detailing the sunken warship's discovery and recovery, we joined one of the

English language guided tours to stand alongside the Vasa's open cannon

ports as the guide gave a detailed description of the background to 17th century

naval warfare, the King's insistence on the warship's scale and armaments, the

events of 10 August 1628 leading up to the sinking, the vessel's recovery and

conservation, and a detailed examination of the causes of the loss. By

coincidence today happened also to be 10 August, 385 years to the day since the Vasa's

fateful sinking. We now had a full 4 hours for close examination of the full

scale of the conserved vessel over its full height at 6 levels, from its keel

below the shallow water line, the 2 cannon decks, higher levels giving clear

views of the Vasa's magnificently decorative wooden sculptures, right up

to a gallery overlooking the full length of the upper deck, masts, rigging and

narrow stern castle (Photo 17 - Vasa's deck, masts, rigging and stern-castle). On 4 of the floors, there were also accompanying

exhibitions with detailed multi-lingual commentaries. Our visit to Vasa Museum: we queued and paid what seemed an

expensive admission of 130kr each, and entered the dimly lit hall: there ahead

stood the Vasa, an utterly staggering sight

(Photo 16 - the conserved warship Vasa). Having viewed the film

detailing the sunken warship's discovery and recovery, we joined one of the

English language guided tours to stand alongside the Vasa's open cannon

ports as the guide gave a detailed description of the background to 17th century

naval warfare, the King's insistence on the warship's scale and armaments, the

events of 10 August 1628 leading up to the sinking, the vessel's recovery and

conservation, and a detailed examination of the causes of the loss. By

coincidence today happened also to be 10 August, 385 years to the day since the Vasa's

fateful sinking. We now had a full 4 hours for close examination of the full

scale of the conserved vessel over its full height at 6 levels, from its keel

below the shallow water line, the 2 cannon decks, higher levels giving clear

views of the Vasa's magnificently decorative wooden sculptures, right up

to a gallery overlooking the full length of the upper deck, masts, rigging and

narrow stern castle (Photo 17 - Vasa's deck, masts, rigging and stern-castle). On 4 of the floors, there were also accompanying

exhibitions with detailed multi-lingual commentaries.

Starting below the waterline, we

were overwhelmed by the immensity of the vessel towering above us, astonished

that 17th century ships of this size had virtually no visible keel and were

almost flat-bottomed. At the ground-floor level, there was further impression of

the Vasa's scale and the level of decorative sculptures which covered the

bows and stern. Originally gilded and painted in

bright colours, as well as

being a formidable fighting machine the ship would also have presented a potent

propaganda weapon symbolising the power and glory of Gustav II Adolfus' Swedish

Kingdom. The next 2 levels gave clear views of the 2 decks of cannon ports

which, when opened showed their lions' heads carved decorations, a terrifying

sight to confront enemy vessels (Photo 18 - Vasa's lion head decorated cannon ports). Information panels gave details of the ship's

features and technical aspects of its working. At this level also we could

examine closely the elaborate wooden sculptures lining the bowsprit in the form

of lines of Roman emperors, culminating in huge rampant lions forming the prow

figurehead (Photo 19 - Carved lions figurehead decorating Vasa's prow). Around at the stern, the huge rear panel of the stern castle was one mass

of beautifully preserved wooden sculptures, the centrepiece of which was a

pair of rampant lions embracing the Vasa crest (see left) (Photo 20 - Carved crest decorating Vasa's stern castle). The galleries enabled close

inspection of this formidable artwork's detailed intricacies, and gave the full

impression of the unbelievable height of the masts; only the lower sections had

been preserved making up just one third of the vessel's original full 50m

height. From the top gallery, we could look down the full length of the ship,

revealing just how narrow the stern had been, one of the factors which for a

vessel of this scale and weight of armaments (72 cannon each weighting one ton)

accounted for the Vasa being so top-heavy and vulnerable to keeling over. bright colours, as well as

being a formidable fighting machine the ship would also have presented a potent

propaganda weapon symbolising the power and glory of Gustav II Adolfus' Swedish

Kingdom. The next 2 levels gave clear views of the 2 decks of cannon ports

which, when opened showed their lions' heads carved decorations, a terrifying

sight to confront enemy vessels (Photo 18 - Vasa's lion head decorated cannon ports). Information panels gave details of the ship's

features and technical aspects of its working. At this level also we could

examine closely the elaborate wooden sculptures lining the bowsprit in the form

of lines of Roman emperors, culminating in huge rampant lions forming the prow

figurehead (Photo 19 - Carved lions figurehead decorating Vasa's prow). Around at the stern, the huge rear panel of the stern castle was one mass

of beautifully preserved wooden sculptures, the centrepiece of which was a

pair of rampant lions embracing the Vasa crest (see left) (Photo 20 - Carved crest decorating Vasa's stern castle). The galleries enabled close

inspection of this formidable artwork's detailed intricacies, and gave the full

impression of the unbelievable height of the masts; only the lower sections had

been preserved making up just one third of the vessel's original full 50m

height. From the top gallery, we could look down the full length of the ship,

revealing just how narrow the stern had been, one of the factors which for a

vessel of this scale and weight of armaments (72 cannon each weighting one ton)

accounted for the Vasa being so top-heavy and vulnerable to keeling over.

The accompanying exhibitions added

further to visitors' understanding of how such a prestigious vessel's artistic

adornments made the ship as much a propaganda weapon as military, promoting the

image of Gustav II Adolfus as the wise, ruthless but forgiving ruler of the

Kingdom. The displays explained how a large 17th century sailing vessel like the Vasa

would have been rigged, sailed and steered, and included one of her conserved

sails found folded in a lower hold sail locker; despite being one of the

smallest top fore-sails, it still covered a vast area of wall setting in context

just how big the main sails would have been. Details of the Vasa's

armaments showed that the objective of 17th century naval battles was not so

much to sink enemy vessels but disable and capture them or their cannons for

your own use; 3 of the Vasa's conserved original bronze cannon were

displayed each weighing one ton and emblazoned with the royal coat of arms (see

right). The

displays explained the stages of the Vasa's construction in the Skeppsgården

ship-yards, the location of her sinking (which we had passed earlier on the

ferry across the harbour), the discovery of the wreck site, her salvaging and

recovery and all the scientific processes in conserving and reconstructing her

timbers, and finally (and most movingly) the skeletal remains of 10 of those who

drowned at the Vasa's sinking with conjectured background on their lives

and appearance. Despite the seemingly expensive admission charge, we had spent

an engaging 5 hours in the Vasa Museum; the conserved ship itself displayed in

her full glory, with the galleries enabling such intimate viewing, together with

the excellently presented detailed exhibitions, made it one of the finest

museums we had seen in our travels, an indisputable 'must see' for anyone

visiting Stockholm. The accompanying exhibitions added

further to visitors' understanding of how such a prestigious vessel's artistic

adornments made the ship as much a propaganda weapon as military, promoting the

image of Gustav II Adolfus as the wise, ruthless but forgiving ruler of the

Kingdom. The displays explained how a large 17th century sailing vessel like the Vasa

would have been rigged, sailed and steered, and included one of her conserved

sails found folded in a lower hold sail locker; despite being one of the

smallest top fore-sails, it still covered a vast area of wall setting in context

just how big the main sails would have been. Details of the Vasa's

armaments showed that the objective of 17th century naval battles was not so

much to sink enemy vessels but disable and capture them or their cannons for

your own use; 3 of the Vasa's conserved original bronze cannon were

displayed each weighing one ton and emblazoned with the royal coat of arms (see

right). The

displays explained the stages of the Vasa's construction in the Skeppsgården

ship-yards, the location of her sinking (which we had passed earlier on the

ferry across the harbour), the discovery of the wreck site, her salvaging and

recovery and all the scientific processes in conserving and reconstructing her

timbers, and finally (and most movingly) the skeletal remains of 10 of those who

drowned at the Vasa's sinking with conjectured background on their lives

and appearance. Despite the seemingly expensive admission charge, we had spent

an engaging 5 hours in the Vasa Museum; the conserved ship itself displayed in

her full glory, with the galleries enabling such intimate viewing, together with

the excellently presented detailed exhibitions, made it one of the finest

museums we had seen in our travels, an indisputable 'must see' for anyone

visiting Stockholm.

Memorial to the 1994 sinking of

M/S Estonia: we emerged into the late afternoon sunlight and

walked across the quayside gardens to see the memorial to the 852 who lost their

lives in a more recent maritime disaster, the sinking of the ferry Estonia

in 1994 sailing across the Baltic from Tallinn to Stockholm. The memorial takes

the form of a triangular walled enclosure inscribed with the names of those

killed (Photo 21 - Memorial to the 852 victims of 1994 Estonia sinking). In 2011 we had visited the memorial set up on the north coast on the

Estonian island of Hiiumaa looking out across the Baltic to where the Estonia

had sunk (see our 2011 log).

We walked around the waterfront looking across to the distant rides of the

Tivoli fairground (Photo 22 - Djurgården Tivoli Fairground rides from across the harbour) and photographed the gloriously palatial building of the Nordiska Museum, reaching the Djurgårdsbron with the western sun streaming

down Lake Mälaren as we crossed the bridge (Photo 23 - Stockholm trams crossing the Djurgårdsbron bridge). Trams from Djurgården island curved

round to run along the waterfront towards the centre, and we were able to catch

one right into the heart of the modern city at Sergelstorg,

stopping right outside T-Centralen for our Metro back out to the campsite. Memorial to the 1994 sinking of

M/S Estonia: we emerged into the late afternoon sunlight and

walked across the quayside gardens to see the memorial to the 852 who lost their

lives in a more recent maritime disaster, the sinking of the ferry Estonia

in 1994 sailing across the Baltic from Tallinn to Stockholm. The memorial takes

the form of a triangular walled enclosure inscribed with the names of those

killed (Photo 21 - Memorial to the 852 victims of 1994 Estonia sinking). In 2011 we had visited the memorial set up on the north coast on the

Estonian island of Hiiumaa looking out across the Baltic to where the Estonia

had sunk (see our 2011 log).

We walked around the waterfront looking across to the distant rides of the

Tivoli fairground (Photo 22 - Djurgården Tivoli Fairground rides from across the harbour) and photographed the gloriously palatial building of the Nordiska Museum, reaching the Djurgårdsbron with the western sun streaming

down Lake Mälaren as we crossed the bridge (Photo 23 - Stockholm trams crossing the Djurgårdsbron bridge). Trams from Djurgården island curved

round to run along the waterfront towards the centre, and we were able to catch

one right into the heart of the modern city at Sergelstorg,

stopping right outside T-Centralen for our Metro back out to the campsite.

We had enjoyed a memorable couple

of days in Stockholm and by being ultra-selective in our visits, we had managed

to cherry-pick what had for us been the best features, avoiding the startlingly

over-expensive admission charges of many places. We were now looking forward

tomorrow to escaping from the sordidly over-crowded Ängby Camping, hoping to

find more acceptable campsites away from the capital city.

Sigtuna, Sweden's oldest

surviving town dating from Viking times: our 3 nights' rent cost

945kr, an amount which would normally buy us at least 4 nights' camping, but the sun was

bright to cheer our departure; we paid in silence but the reckoning was still to

come when we set in train our complaints to the fire authorities and place

the kiss-of-death on this dreadful place in our campsites review. Today we were

heading back north to Uppsala but on the way planned to call at Sigtuna,

Sweden's oldest borough dating back to Viking times. The satnav guided us

through a circuitous labyrinth of motorways Sigtuna, Sweden's oldest

surviving town dating from Viking times: our 3 nights' rent cost

945kr, an amount which would normally buy us at least 4 nights' camping, but the sun was

bright to cheer our departure; we paid in silence but the reckoning was still to

come when we set in train our complaints to the fire authorities and place

the kiss-of-death on this dreadful place in our campsites review. Today we were

heading back north to Uppsala but on the way planned to call at Sigtuna,

Sweden's oldest borough dating back to Viking times. The satnav guided us

through a circuitous labyrinth of motorways

eventually leading to the E4

northwards and we joined the intolerantly aggressive traffic. Continuing north,

we turned off into the centre of the little town of Sigtuna. Although today a

small and unassuming town of 8,000 inhabitants, Sigtuna played an important part

in Sweden's early history and lays claims to being Sweden's oldest town. Founded by

King Eric in 980 AD on the shores of a

northern arm of Lake Mälaren, Sigtuna grew in significance as a royal trading

centre to become in the 11th century Sweden's most important town,

eclipsing Stockholm which at that time was still an obscure village. Such an

important royal domain was Sigtuna that Sweden's first coins were minted here

around 1000 AD. In 1230 the Dominican Order founded a monastery here which

played a leading role in Sweden's early medieval ecclesiastical history

producing many archbishops. But by 1300 Sigtuna was overtaken in significance by

fast developing Stockholm, while Sigtuna remained a small town. Despite a

devastating fire in late medieval times, the main church survived and the town

grew again around its original street plan. Its main street Storgatan still

follows its original route, claimed as Sweden's oldest street now under the line

of the modern street, lined with picturesque wooden shops and a regular summer

visitor attraction. eventually leading to the E4

northwards and we joined the intolerantly aggressive traffic. Continuing north,

we turned off into the centre of the little town of Sigtuna. Although today a

small and unassuming town of 8,000 inhabitants, Sigtuna played an important part

in Sweden's early history and lays claims to being Sweden's oldest town. Founded by

King Eric in 980 AD on the shores of a

northern arm of Lake Mälaren, Sigtuna grew in significance as a royal trading

centre to become in the 11th century Sweden's most important town,

eclipsing Stockholm which at that time was still an obscure village. Such an

important royal domain was Sigtuna that Sweden's first coins were minted here

around 1000 AD. In 1230 the Dominican Order founded a monastery here which

played a leading role in Sweden's early medieval ecclesiastical history

producing many archbishops. But by 1300 Sigtuna was overtaken in significance by

fast developing Stockholm, while Sigtuna remained a small town. Despite a

devastating fire in late medieval times, the main church survived and the town

grew again around its original street plan. Its main street Storgatan still

follows its original route, claimed as Sweden's oldest street now under the line

of the modern street, lined with picturesque wooden shops and a regular summer

visitor attraction.

We walked along Storgatan and

found the TIC housed in a former 18th century inn, the Dragon, where the

girl provided us with an informative guide leaflet, highlighting for us the

historical sites and rune stones around the town. As an indication of Sigtuna's

10~11th century wealth and importance, some 150 rune stones have been found in

the area usually set up as memorials alongside ancient roads. Several of these

are scattered around the town's central area, some even in modern gardens. We

set off to walk the circuit. Just off the central square the tiny 18th century Rådhus, said to be Sweden's smallest town hall, was in process of re-roofing and

covered with scaffolding. Just beyond, up Olofsgatan we found the ruins of St

Olof's church founded in the 12~13th centuries, with its sturdily thick stone

walls and short stubby nave, still surrounded by a modern graveyard (see above

left) (Photo 24 - Ruins of 12~13th century St Olof's Church at Sigtuna). At the 1530

Reformation, Gustav Vasa ordered closure of all the country's monasteries and as

a result the Dominican priory was demolished and its church became the

Protestant parish church of St Mary. As a result, the town's We walked along Storgatan and

found the TIC housed in a former 18th century inn, the Dragon, where the

girl provided us with an informative guide leaflet, highlighting for us the

historical sites and rune stones around the town. As an indication of Sigtuna's

10~11th century wealth and importance, some 150 rune stones have been found in

the area usually set up as memorials alongside ancient roads. Several of these

are scattered around the town's central area, some even in modern gardens. We

set off to walk the circuit. Just off the central square the tiny 18th century Rådhus, said to be Sweden's smallest town hall, was in process of re-roofing and

covered with scaffolding. Just beyond, up Olofsgatan we found the ruins of St

Olof's church founded in the 12~13th centuries, with its sturdily thick stone

walls and short stubby nave, still surrounded by a modern graveyard (see above

left) (Photo 24 - Ruins of 12~13th century St Olof's Church at Sigtuna). At the 1530

Reformation, Gustav Vasa ordered closure of all the country's monasteries and as

a result the Dominican priory was demolished and its church became the

Protestant parish church of St Mary. As a result, the town's

other churches

including St Olof's fell into ruins. Across the lane the Mariakyrkan stood in

its own graveyard, built of red brick in the 13th century to serve the Dominican

monastery and post-Reformation to become the parish church, a role it still

fulfils, its appearance now much as it was 700 years ago (see above right). A 15th century carved

wooden reredos stood behind the altar with a parade of saints either side of

Christ and Mary Queen of Heaven (see right). It was a truly beautiful church with 15th

century murals lining the vaulting of the north nave. Outside in the graveyard,

an 11th century runestone memorial stood alongside a beautifully recreated herb

garden recalling the former monastery. other churches

including St Olof's fell into ruins. Across the lane the Mariakyrkan stood in

its own graveyard, built of red brick in the 13th century to serve the Dominican

monastery and post-Reformation to become the parish church, a role it still

fulfils, its appearance now much as it was 700 years ago (see above right). A 15th century carved

wooden reredos stood behind the altar with a parade of saints either side of

Christ and Mary Queen of Heaven (see right). It was a truly beautiful church with 15th

century murals lining the vaulting of the north nave. Outside in the graveyard,

an 11th century runestone memorial stood alongside a beautifully recreated herb

garden recalling the former monastery.

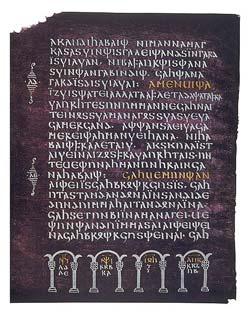

Just along Prästgatan we passed

another of Sigtuna's many runestones, and a stone tower, all that survived of St Lar's church, standing atop a hillock. Turning up the aptly named Runstigen

(Rune Pathway), we passed 2 further surviving rune stone memorials set up to

commemorate family members (Photo 25 - 10~11th century rune stone memorial at Sigtuna); the runic inscriptions translated as: Sven had

this stone erected in memory of his father, and Frödis in memory of her husband

Ulv. God rest his soul and Oleg had this stone erected in

memory of his 2 sisters Tora and Rodvi (see left and right). Across Persgatan we reached the

ruins of St Per's church set prominently on a hilltop and once the royal church,

probably an early cathedral. The beautiful vaulting of the central tower showed

early transition from rounded Romanesque to ogival Gothic arches. Most of the

surviving structure dated from the 13th century making this church

contemporaneous with the earliest parts of our home village church. From here we

walked down to the town's little marina on the shore of Lake Mälaren where

Sunday afternoon visitors gathered for ice creams. We returned along past the

wooden cottages, now twee tourist shops, of Storgatan (Photo 26 - Sigtuna's Storgatan, Sweden's oldest street), completing our tour of

Sigtuna's beautiful churches and runestones, an insightful glimpse into

Sweden's medieval history, to continue our journey on to Uppsala, . Just along Prästgatan we passed

another of Sigtuna's many runestones, and a stone tower, all that survived of St Lar's church, standing atop a hillock. Turning up the aptly named Runstigen

(Rune Pathway), we passed 2 further surviving rune stone memorials set up to

commemorate family members (Photo 25 - 10~11th century rune stone memorial at Sigtuna); the runic inscriptions translated as: Sven had

this stone erected in memory of his father, and Frödis in memory of her husband

Ulv. God rest his soul and Oleg had this stone erected in

memory of his 2 sisters Tora and Rodvi (see left and right). Across Persgatan we reached the

ruins of St Per's church set prominently on a hilltop and once the royal church,

probably an early cathedral. The beautiful vaulting of the central tower showed

early transition from rounded Romanesque to ogival Gothic arches. Most of the

surviving structure dated from the 13th century making this church

contemporaneous with the earliest parts of our home village church. From here we

walked down to the town's little marina on the shore of Lake Mälaren where

Sunday afternoon visitors gathered for ice creams. We returned along past the

wooden cottages, now twee tourist shops, of Storgatan (Photo 26 - Sigtuna's Storgatan, Sweden's oldest street), completing our tour of

Sigtuna's beautiful churches and runestones, an insightful glimpse into

Sweden's medieval history, to continue our journey on to Uppsala, .

On to Uppsala and a closed

campsite: we headed north on minor roads looking forward to settling

into Sunnersta Camping in the southern outskirts of Uppsala, but on arrival it

was clear that the place was no longer open. There was no alternative but to

continue into the city along Dag Hammarskjöld Väg to find the far less attractive

sounding Fyrishov Camping adjacent to a swimming and sports centre closer in to

the city. The long drive into Uppsala took us past a number of modern scientific

institutes and departments of Uppsala University, and just north of the city

centre we reached Fyrishov. First impressions seemed to confirms our fears: a

large swimming complex with an apparently amorphous campsite next door.

With heavy hearts we booked in at reception, but the young staff were pleasantly

welcoming and helpful, suggesting a pitch by the huts and close to the service

building in response to our request for a quiet corner. We reserved the pitch,

but before settling in we needed to find a hypermarket or IKEA to replace our

kettle which had failed. The young staff readily identified a large retail

complex in the NE outskirts of the city and we set off following their

directions around Tycho Hedens Väg ring road. Eventually finding a way into the

acres of car parks, we tried IKEA; this iconic representation of Swedish

entrepreneurial commercialism must surely be able to supply a suitable electric

kettle. But no - household goods of every description and elaboration, but no

electrical goods. With closing time approaching, we tried other stores but

without success: no electric kettles of suitable low power rating. We should

have to try other places tomorrow, and dodging a monumental rain storm, we

returned to the campsite after a day of cultural extremes - medieval Sigtuna to

21st century commercial estates and IKEA.

The royal and religious

cult-centre of Gamla Uppsala: our plan was to spend our first day at

Gamla (Old) Uppsala. The modern settlement is now a pleasant suburb of the city,

but across the main railway tracks you enter a wholly mystical world of

Sweden's ancient past. As early as the 3~4th centuries AD, Gamla Uppsala in the

wolds of the River Fyris valley had been an important religious, political and

economic sacred cult centre, the residence of the Swedish kings of the legendary

Yngling dynasty. The earliest of Scandinavian sources speak of the Gamla Uppsala cult site as the seat of royal power, royal

burial ground and site of a great pagan temple, the royal centre of the Svear tribe where from

pre-historic times the king summoned the general assembly (Thing) and a great

religious celebration was held. The late 12th century Danish chronicler Saxo

Grammaticus speaks of Odin himself having his residence at Old Uppsala, and the

13th century Icelandic saga story-teller Snorri Sturluson depicted it as the

home of the Yngling dynasty and of the god Freyr at whose temple here great

sacrificial festivals were held in the god's honour. The 11th century chronicler

Adam of Bremen describes a magnificent golden temple at Old Uppsala where human

sacrifices were made every 9th year in honour of the gods Odin, Thor and Freyr.

Although all the sources were writing 200 years after the events, it was clearly

the seat of royal power of the Svear clan and a major cult centre of the pagan

Norse gods. It is testimony of Gamla Uppsala's religious significance that, with

the Swedes' conversion to Christianity around 1090 AD and the country's receipt

of its first archbishopric in 1164, the first cathedral was located here on the site

of the former pagan temple. Under a clay plateau alongside the present church,

archaeologists have unearthed the remains of a large ceremonial feasting hall,

the centre of the royal kungsgården (royal estate). The royal and religious

cult-centre of Gamla Uppsala: our plan was to spend our first day at

Gamla (Old) Uppsala. The modern settlement is now a pleasant suburb of the city,

but across the main railway tracks you enter a wholly mystical world of

Sweden's ancient past. As early as the 3~4th centuries AD, Gamla Uppsala in the

wolds of the River Fyris valley had been an important religious, political and

economic sacred cult centre, the residence of the Swedish kings of the legendary

Yngling dynasty. The earliest of Scandinavian sources speak of the Gamla Uppsala cult site as the seat of royal power, royal

burial ground and site of a great pagan temple, the royal centre of the Svear tribe where from

pre-historic times the king summoned the general assembly (Thing) and a great

religious celebration was held. The late 12th century Danish chronicler Saxo

Grammaticus speaks of Odin himself having his residence at Old Uppsala, and the

13th century Icelandic saga story-teller Snorri Sturluson depicted it as the

home of the Yngling dynasty and of the god Freyr at whose temple here great

sacrificial festivals were held in the god's honour. The 11th century chronicler

Adam of Bremen describes a magnificent golden temple at Old Uppsala where human

sacrifices were made every 9th year in honour of the gods Odin, Thor and Freyr.

Although all the sources were writing 200 years after the events, it was clearly

the seat of royal power of the Svear clan and a major cult centre of the pagan

Norse gods. It is testimony of Gamla Uppsala's religious significance that, with

the Swedes' conversion to Christianity around 1090 AD and the country's receipt

of its first archbishopric in 1164, the first cathedral was located here on the site

of the former pagan temple. Under a clay plateau alongside the present church,

archaeologists have unearthed the remains of a large ceremonial feasting hall,

the centre of the royal kungsgården (royal estate).

Not only is Gamla Uppsala

associated with the royal power base and religious centre, the sandy ridge had

been a significant burial site for some 2,000 years with many burial mounds of

which traces of some 250 remain. The most prominent burial mounds visible today

are 3 huge 9m high mounds dating back to the 5~6th centuries AD and constructed

along the line of the ridge (see above right). According to ancient mythology, these were the final

resting places of the 3 pagan gods Thor, Odin and Freyr. Legend also has it that