|

*** AUSTRALIA 2011 - ADELAIDE *** |

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Onward flight from Sydney to Adelaide: after our final Big Hostel breakfast, we re-packed our kit yet again ready for the next leg of our journey, and just after 10-30am checked out and collected our $20 key deposit. After yesterday afternoon's stormy downpour, this morning the sky was clear blue again and sun shining, for our final walk back across to Central Station where we bought our $15 tickets for the Airport Express out to Terminal 3, the Qantas domestic flights terminal.

Arrival at Sydney Airport:

out at Sydney Airport, check-in was only possible via the automated terminals; human interaction was not available for mere

economy class passengers such as us. Sheila deftly navigated her way around the

automated check-in process, and printed off our boarding passes along with

hold-luggage labels (Photo

1: Sydney Airport). Scales were available accurately to check both hold- and

hand-luggage weights. Despite the apparent heavy weight of our packs, which now

included the souvenir history of the NSW Parliament, we were both well within

the respective maximum allowable weights of

23 kgms and 7 kgms.

We handed in our hold-luggage, and sent a text to our daughter saying: 2 weary travellers

on the way; they need washing machine, bath, food, and could you lend us a

couple of bob. Role reversal! Arrival at Sydney Airport:

out at Sydney Airport, check-in was only possible via the automated terminals; human interaction was not available for mere

economy class passengers such as us. Sheila deftly navigated her way around the

automated check-in process, and printed off our boarding passes along with

hold-luggage labels (Photo

1: Sydney Airport). Scales were available accurately to check both hold- and

hand-luggage weights. Despite the apparent heavy weight of our packs, which now

included the souvenir history of the NSW Parliament, we were both well within

the respective maximum allowable weights of

23 kgms and 7 kgms.

We handed in our hold-luggage, and sent a text to our daughter saying: 2 weary travellers

on the way; they need washing machine, bath, food, and could you lend us a

couple of bob. Role reversal!

After a burger lunch in the airport cafeteria, we bought cuddly kangaroos to take back as presents for our grandchildren. A ribald remark to the sales lady about selling off the 2011 Test series souvenir caps, after England's convincing victory over the Aussies to retain the Ashes, brought the response that, sure enough, they were indeed half-price; an early birthday present for Paul! Domestic flight

from Sydney to Adelaide: we sat and waited at the Gate 5 lounge for the

14-05 flight to Adelaide (see above right) and on boarding, the Boeing 737

aircraft seemed tiny compared with the long-haul 747. Afternoon tea and cakes were served, and the two hours' flight passed remarkably

An initial tour of Adelaide and the Adelaide Hills: driving into Adelaide, with a running commentary as we passed notable features of the city and the distant surrounding Adelaide Hills, helped us to get our bearings. Passing through the city centre, we headed out to the SE to join the main highway which eventually continued to Melbourne some 1,200 kms distant. The highway climbed by a new route cut directly up into the Adelaide Hills; we turned off on the spectacular old road which zigzagged up through the wooded hills to the summit of Mount Lofty. The woods of eucalyptus which covered the hills harboured Koalas and Kangaroos, although we saw none today. On reaching the summit, we stood at the 2,000 feet lookout with the distant city spread across the plain below lit by the western sun (see left). The day unfortunately was beginning to turn misty and stormy, meaning we could see little detail, and it was noticeably cooler up here. For the first time also, it was evident how the autumn colours were beginning to show.

In the late 1820s, a group of British profiteering speculators, led by the unscrupulous Edward Wakefield, promoted a venture to found a colony in South Australia based on self-supporting free settlement rather than convict labour. Instead of granting free land to settlers as had happened in other colonies, the land should be sold, and the money from land sales used to transport skilled workers rather than paupers and convicts. In 1834 the South Australian Association persuaded Parliament to pass the South Australian Colonisation Act. Wakefield wanted the new colony's capital to be called Wellington after the Iron Duke; but in giving royal assent, King William IV decreed that it should be named Adelaide in honour of his Queen-Consort, Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen. A Board of Commissioners was formed to organise the colonial venture: land was advertised and preliminary purchase land orders were sold; ships carrying the first settlers set sail from London in February 1836, and landed first on Kangaroo Island off the south coast. They were moved to Holdfast Bay, site of present-day Glenelg when the first Governor, John Hindmarsh (see below left) arrived in HMS Buffalo in December 1836, and the proclamation was made of the South Australian colony's foundation.

In March 1837, colonists who had already purchased land plots before embarking were given first choice of surveyed land, and the remaining plots were auctioned for 2~14 guineas. Within a few weeks many of the same plots were selling at £80~100. With the town survey completed, Light's poorly paid and ill-equipped surveying team was expected to begin another massive task of surveying at least 405 km² of rural land. By December 1837, Light who was slowly succumbing to tuberculosis, had managed to complete 243 km², by which time the population had increased to around 2,500. The first sheep were brought in from Tasmania or over-landed from New South Wales from 1838, with the wool industry forming the basis of South Australia's economy for the first few years. Vast tracts of land were leased for grazing by squatters until required for agriculture. Once the land was surveyed it was put up for sale and the squatters had to buy their runs or move on. Most bought their land when it came up for sale, to the detriment of wheat farmers who had a hard time finding unoccupied fertile land. Farms took longer to establish than sheep runs and were expensive to set up. Despite this, by 1860 wheat farms ranged from Encounter Bay in the south to the Clare Valley in the north. Adelaide's second Governor was Colonel George

Gawler who arrived in October 1838 to a situation of almost no public finances,

underpaid officials and 4,000 immigrants still living in makeshift

accommodation. Gawler's first task was to

address delays over rural settlement and agriculture. He persuaded Sturt in New

South Wales to become surveyor-general, and appointed increased numbers of

better paid colonial officials; he established a police force and undertook exploration of

the surrounding territory. He also built a Governor's House, jail, police barracks, hospital,

and customs house and wharf at Port Adelaide. But by the 1840s, the land boom tailed off, cash

and credit were scarce, explorations indicated

limited fertile land,

and British speculators turned their attention elsewhere.

Gawler increased public expenditure to prevent an economic collapse, and the

British Government had to step in with grants to bail-out the colony and prevent bankruptcy.

From the time of the city's 1836 foundation,

the Surveyor General Colonel William Light planned for the new colony of Adelaide to

include a botanic garden in its parklands. Despite problems of flooding at the

designated River Torrens site, the gardens were eventually laid out and opened

in 1857 with the entrance off North Terrace (see above right). This beautiful

area of parkland (Photo

4: Botanic Gardens), laid out with lawns and ponds in the English

style, is now planted with many

species of Australian trees and shrubs (see left), along with extensive displays of

Palms,

Cycads and Bromeliads. As we walked through the gardens, the trees We continued through the trees and lawns to the Amazon Water Lily Pavilion, its pond filled with vast water lily species (Photo 7: Amazon Water Lilies). On through gardens of Mediterranean and xerophytic plants, and an area of Australian forest plants. Many of the species presented, both native to Australia and other tropical regions are grown as house plants in UK, but here were enormous; an example was the Swiss Cheese plant (Monstrea deliciosa) native to Central America (Photo 8 - Swiss Cheese Plant). We reached the huge Bicentennial Conservatory, said to be the largest glass house in the southern hemisphere, which houses a complete tropical rain forest of huge plant species from the tropical regions of Queensland and SE Asia. This was fascinating to wander through amid the huge ferns and exotic tropical trees and shrubs (see below left); we followed the marked, multi-level trail detailed in the leaflet provided, taking many photographs in this wonderfully conserved and presented rainforest environment amid typical tropical species (Photo 9 - Fish-tail Palms).  North Terrace and the Migration Museum:

there was still much to be seen in the Botanic Gardens, but by now it was almost

1-00pm and time to find some lunch. There would be plenty of opportunity to

return another day to explore more of the gardens, and to find Adelaide's

Wollemi Pine specimen. We returned to North Terrace and the Migration Museum:

there was still much to be seen in the Botanic Gardens, but by now it was almost

1-00pm and time to find some lunch. There would be plenty of opportunity to

return another day to explore more of the gardens, and to find Adelaide's

Wollemi Pine specimen. We returned to North Terrace; the pub on the corner of

Hutt Street looked temptingly traditional (see right), but instead we found a

small Vietnamese café just along Rundle Street for huge bowls of delicious

Wonton soup, a thin broth with vermicelli noodles and chicken and prawn wontons,

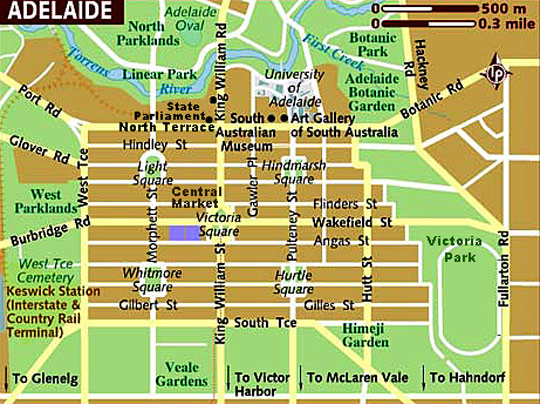

and Pho beef rice noodle soup. Returning to North Terrace (Map of Central Adelaide), we

strolled along past the grand parade of civic buildings, including the

Universities of South Australia and Adelaide (see below right). The road was lined with statues of 19th century

imperious worthies involved in the development of the

South Australian colony-state. Beyond the neo-Gothic Art Gallery, we reached the city's Museum of

South Australia. The entrance hall was filled with the huge skeletons of whales

and porpoises, and the Aboriginal Culture Gallery proved a worthy but wearisome

display of native artefacts

and artwork; the rest of the museum's displays similarly attracted little attention, and

we continued past the State Library, around into Kintore Avenue to find the

Migration Museum. This was a far more interesting if gruellingly challenging

presentation: the displays told the history of 19th and 20th century white

settlement of SA, detailing the often heart-rending reasons that caused settlers to

migrate, and the even more tragic impact on the indigenous population. The

museum traced the consequences of the controversial White Australian policy of

the early~mid 20th century, the history of the post-WW2 £10 Poms migrants scheme, and

of multi-cultural refugees

and asylum seekers of more recent years. Of particular poignancy

for us were the memorial plaques on the outer wall commemorating all the Central

and Eastern European refugees from political oppression who had settled in South

Australia: Slovenes, Serbs, Croats, Bosnian-Herzegovinians, Poles, Hungarians,

Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians, Pontic Greeks, Ukrainians, Jews, Armenians,

Tatars-Bashkirs

(Photo

10: Central/Eastern European Migrants); and most

tragically of all the enforced British Child Migrants,

victims of a shamefully sordid North Terrace; the pub on the corner of

Hutt Street looked temptingly traditional (see right), but instead we found a

small Vietnamese café just along Rundle Street for huge bowls of delicious

Wonton soup, a thin broth with vermicelli noodles and chicken and prawn wontons,

and Pho beef rice noodle soup. Returning to North Terrace (Map of Central Adelaide), we

strolled along past the grand parade of civic buildings, including the

Universities of South Australia and Adelaide (see below right). The road was lined with statues of 19th century

imperious worthies involved in the development of the

South Australian colony-state. Beyond the neo-Gothic Art Gallery, we reached the city's Museum of

South Australia. The entrance hall was filled with the huge skeletons of whales

and porpoises, and the Aboriginal Culture Gallery proved a worthy but wearisome

display of native artefacts

and artwork; the rest of the museum's displays similarly attracted little attention, and

we continued past the State Library, around into Kintore Avenue to find the

Migration Museum. This was a far more interesting if gruellingly challenging

presentation: the displays told the history of 19th and 20th century white

settlement of SA, detailing the often heart-rending reasons that caused settlers to

migrate, and the even more tragic impact on the indigenous population. The

museum traced the consequences of the controversial White Australian policy of

the early~mid 20th century, the history of the post-WW2 £10 Poms migrants scheme, and

of multi-cultural refugees

and asylum seekers of more recent years. Of particular poignancy

for us were the memorial plaques on the outer wall commemorating all the Central

and Eastern European refugees from political oppression who had settled in South

Australia: Slovenes, Serbs, Croats, Bosnian-Herzegovinians, Poles, Hungarians,

Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians, Pontic Greeks, Ukrainians, Jews, Armenians,

Tatars-Bashkirs

(Photo

10: Central/Eastern European Migrants); and most

tragically of all the enforced British Child Migrants,

victims of a shamefully sordid

policy sponsored by both the British and

Australian governments which continued as late as the 1980s (see left). This was a truly moving policy sponsored by both the British and

Australian governments which continued as late as the 1980s (see left). This was a truly moving experience, shedding light on some of the tragic human history which influenced

South Australia's settlement and its current mixed population and cultures.

experience, shedding light on some of the tragic human history which influenced

South Australia's settlement and its current mixed population and cultures.Passing the prominent South African War Memorial equestrian statue further along North Terrace and the SA State Parliament Building opposite, we reached Government House at the corner of King William Road, the official residence of South Australia's Governor and the city's oldest public building completed in 1855. It was by now however almost 5‑00pm and beginning to get dusky. From here we began the long return walk along King William Street, the main north~south thoroughfare of Adelaide's grid-plan of streets (Map of Central Adelaide). We paused at the Tourist Information Centre for further information on the city, and just around the corner along Rundle Mall, the main shopping street busy with pedestrians, we bought stamps for our post cards home. At the far end junction with Pulteney Street, we turned south but progress was slow with the need to wait for traffic lights at every intersection in the busy evening rush hour traffic. Weary from today's city explorations, we enjoyed our first taste of Cooper's Adelaide beers (see right) at the General Havelock pub at the corner of Hutt Street before returning to our daughter's apartment for a barbecue supper. After a memorably successful first day in Adelaide, we were beginning to get the lie of the land in the city.

Tram

along King William Street:

the following morning, we found our way back to King William Street. The

street had been named after King William IV, the British monarch at the time of

Adelaide's foundation in 1836; his queen-consort, Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, had

given the city its name, and her statue stands in the foyer of Adelaide Town

Hall. At King William Street we found the tram line with narrow platforms in

the centre of the road, and waited for

Getting to grips with

Adelaide public transport, and with Aussie beer-glass terminology:

our plan for today was to investigate the

possibility of visiting the South Australian State Parliament; crossing

North Terrace, we made enquiries at Parliament House. Visiting was only

Our options were to make a follow-up visit to the Botanic Gardens, or visit the Tandanya Aboriginal Cultural Institute. By the time we had bought a sandwich in Rundle Mall however, there was really time for neither. So we relaxed to eat our sandwich lunch with a Cooper's beer sitting at the outside terrace of the Stag Hotel at the corner of Rundle Street opposite the Parks (see above right). Paul tried to draw on his experience of NSW beer glass sizes, none of which helped in SA where a NSW schooner was called a pint, a pot turned out to be thimble sized, and a SA schooner was an even smaller measure; all totally bemusing!

After being shown the

parliamentary library, we were taken through to see the Legislative Council, the Upper House

(Photo

13: Legislative Council), laid out on

the Westminster model of the House of Lords with red leather benches. The

electorate votes in 4-yearly State elections with two ballot papers, one for the

House of Assembly, and one for the 22 seat Legislative Council whose members

serve for a maximum of 2 terms, 8 years. The Upper House elects its own

presiding officer, called the President of the Legislative Council. Again we

were free to photograph the Chamber. Paul asked about relations between Federal and

State legislatures and Local Councils, and whether there were tensions over

levels of responsibilities and degree of devolved powers between the

Tandanya National Aboriginal Cultural Institute: having photographed the outside of the Parliament building at the corner of King William Road (see left), we caught the bus back along North Terrace around to Grenfell Street to visit Tandanya National Aboriginal Cultural Institute. It turned out to be a gallery managed by local aboriginal Kaurna people, with various displays of contemporary aboriginal visual art; the current exhibition certainly could not be described as enthralling! We made a brave attempt to show interest, and enjoyed a few moments' rest during screening of a shaky black and white film of indigenous peoples stamping their feet; at least that was what it seemed to be! A further few moments were spent examining the $560 didgeridoos in the gift shop, and that was it. It was all something of a non-event, despite the publicity attempts to hype the place, and all rather sad, somehow symbolic of the fate of aboriginal peoples. All in all however today had been another enjoyably fulsome day, enabling us to gain further thorough knowledge of Adelaide.

Tram ride out to seaside town of Glenelg:

the following morning, we set off for our day at

the seaside town of Glenelg down at the coast just to the south-west of the

city. Along Halifax Street to the intersection with King

Bay Discovery Centre at Glenelg's Town Hall: Glenelg's Town Hall housed the impressive the Bay Discovery Centre, a social

history and heritage museum documenting life in Glenelg from the earliest

foundation of the colony in 1836 through to modern times. This seemed a good

place to start our visit to Glenelg, since the weather had become overcast with

threat of a shower. We were welcomed by enthusiastic volunteer guides who

also provided town maps for later. The initial displays told the story of the

seemingly exploitational venture capitalists who sold plots of land in the new

colony, inspired by the unscrupulous Edward Wakefield who stood to profit

mightily by promoting the colonisation of SA. They also illustrated the wretched lives of the poor

settlers who were lured here from the industrial slums of England or the famine

of Ireland and Scotland by overstated promises of a new life in South Australia.

Further displays told the history of Colonel William Light, the Surveyor-General

who was charged by the Crown with surveying the land and establishing the most

appropriate site and layout for the new colonial city of Adelaide. Governor Hindmarsh wanted the city to be founded on the coast at the harbour of Port

Lincoln on the Lower Eyre Peninsula. Light stubbornly resisted this, fearing the  but now

replaced by a new and modern metro system. Other displays showed the growth

and popularity of Glenelg as a seaside resort, and the display on early beach

dress etiquette recorded prosecution of three men for topless bathing! The city

council's chamber was open to visitors, and the volunteer attendant told us a

little about local authorities and taxation in Australia, surprised at our

questioning him about this lowest tier of civic government. A formal portrait of

a very young Queen Elizabeth II hung above the mayor's chair (see above left); this somehow seemed

symbolic of the Australian nostalgic view of the British monarchy. Paul made the

mistake of asking about the issue of a future break with the monarchy as

Australian Head of State, and we only managed to excuse ourselves from the

prolonged debate about the issue by insisting that lunch was calling! But still

we could not escape without further conversation with another of the volunteers,

who recounted at length how he had emigrated to SA from Harrogate in the 1950s,

not as a £10 Pom (he determinedly insisted), but by his own efforts and expense.

But partly through the enthusiasm of the museum volunteers, we had in fact learned a

lot about South Australia's history, and Glenelg's part in it. but now

replaced by a new and modern metro system. Other displays showed the growth

and popularity of Glenelg as a seaside resort, and the display on early beach

dress etiquette recorded prosecution of three men for topless bathing! The city

council's chamber was open to visitors, and the volunteer attendant told us a

little about local authorities and taxation in Australia, surprised at our

questioning him about this lowest tier of civic government. A formal portrait of

a very young Queen Elizabeth II hung above the mayor's chair (see above left); this somehow seemed

symbolic of the Australian nostalgic view of the British monarchy. Paul made the

mistake of asking about the issue of a future break with the monarchy as

Australian Head of State, and we only managed to excuse ourselves from the

prolonged debate about the issue by insisting that lunch was calling! But still

we could not escape without further conversation with another of the volunteers,

who recounted at length how he had emigrated to SA from Harrogate in the 1950s,

not as a £10 Pom (he determinedly insisted), but by his own efforts and expense.

But partly through the enthusiasm of the museum volunteers, we had in fact learned a

lot about South Australia's history, and Glenelg's part in it.

Fish and chip lunch at Glenelg: by the time we finally extricated ourselves, it

was almost 1-00pm, by which time the weather was much improved and the sun

almost out. Taking Rough Guide's advice on lunch venue, we bought take-away fish

and chips from the Bay Fish Shop, the fish being Tommy Ruff (Australian

herring), a delicious, fine textured A stroll along Glenelg Jetty: after lunch, we paused for an over-expensive beer at the bar of the Jetty Hotel, then along with local people we strolled out along Glenelg Jetty (see above left) in the now lovely autumn sunshine (Photo 17: Glenelg Jetty). Glenelg Jetty was built in 1859 with lighthouse at the outer end and railway track, to service cargo and mail ships until replaced by Port Adelaide as the colony's main harbour. Given the shallow coastal waters, the original Jetty needed to be 381m (1,250 feet) long out to deep water to allow anchorage for ocean-going vessels; it later suffered storm damage, and was replaced by the present shorter structure in 1969, still an impressive 215m (705 feet) in length. Glenelg's beach stretched away in both directions (see above left) (Photo 18: Glenelg white sand beach); with the sun now very hot and the light ultra-bright, it seemed to us that the white sands were remarkably deserted, but then it was the Australian equivalent of November, despite today's glorious weather. This central area of Glenelg by the Jetty was pleasantly laid out with parkland; Magpie Larks strutted around the seafront gardens (Photo 19: Magpie Lark), and the Jetty stretched away seaward beyond (see above right).  Glenelg's Old Gum Tree: back at the town

hall, we set off walking in the hot sun to see Glenelg's other famous feature

associated with the 1836 settlers' landings and Governor Hindmarsh's

proclamation of the new colony's foundation, the Old Gum Tree. Around by the yachting marina at

the estuary of the Patawalonga River, a rather pseudo replica of Governor Hindmarsh's ship

HMS Buffalo moored here (Photo

20: HMS Buffalo replica) now served as a floating restaurant

(see above left).

The park alongside was delightful with children playing on the swings in the hot

afternoon sunshine. We plodded on and turned down MacFarlane Street in search of

the conserved remains of the Old Gum Tree, under which Governor Hindmarsh is

said Glenelg's Old Gum Tree: back at the town

hall, we set off walking in the hot sun to see Glenelg's other famous feature

associated with the 1836 settlers' landings and Governor Hindmarsh's

proclamation of the new colony's foundation, the Old Gum Tree. Around by the yachting marina at

the estuary of the Patawalonga River, a rather pseudo replica of Governor Hindmarsh's ship

HMS Buffalo moored here (Photo

20: HMS Buffalo replica) now served as a floating restaurant

(see above left).

The park alongside was delightful with children playing on the swings in the hot

afternoon sunshine. We plodded on and turned down MacFarlane Street in search of

the conserved remains of the Old Gum Tree, under which Governor Hindmarsh is

said

to have read out the proclamation of the new colony's foundation in 1836.

As we paused at a bus stop, trying to figure out if the local

volunteer-operated free circular bus would help us find our way out

to the Old Gum Tree, one of the mini-buses stopped. Unfortunately their route

did not pass the historic site, but the driver helpfully gave us directions. We

plodded on, crossing Tapleys Hill Road where another bus stop showed buses

stopped here on the way back to Jetty Street; this would give us time to visit

the Old Gum Tree and catch the bus back to the centre. to have read out the proclamation of the new colony's foundation in 1836.

As we paused at a bus stop, trying to figure out if the local

volunteer-operated free circular bus would help us find our way out

to the Old Gum Tree, one of the mini-buses stopped. Unfortunately their route

did not pass the historic site, but the driver helpfully gave us directions. We

plodded on, crossing Tapleys Hill Road where another bus stop showed buses

stopped here on the way back to Jetty Street; this would give us time to visit

the Old Gum Tree and catch the bus back to the centre.

Further along MacFarlane Street, in the midst of a rather exclusive middle class

housing estate, we finally found the Old Gum Tree (Photo

21: Old Gum Tree), or rather what remained of it: a lifeless and

concrete-reinforced arched stump with a protective covering, looking for all the

world like some bizarre prehistoric animal (see above and below right).

In 2003 Victoria Square was officially assigned the second name

of Tarntanyangga, meaning red kangaroo rock in the language

of the indigenous Kaurna inhabitants, as part of the dual naming initiative by

Adelaide City Council. Tarntanyangga had been an important centuries-old ceremonial gathering place for indigenous

peoples. During the 1960s the Aboriginal community renewed its activities in

Victoria Square, with the area again becoming a focus for social, political and community-based

indigenous events, such

as the National Sorry Day commemoration held each year in May, and the National Aborigines and Islanders Day

Observance Committee Week celebrations each July. The Australian Aboriginal flag

(see left)

As we reached Victoria Square today, this was the clearest and hottest day so far of

our time in Australia; even in autumn, the temperature in Adelaide this

morning was 27ºC, more than hot enough for us. Amid the passing traffic, Victoria Square was a delightful green oasis

with broad lawns and flower-beds (Photo

25: Green oasis),

surrounded by high-rise office blocks of the modern city together with a scattering of

more distinguished

older looking buildings. Colonel Light would surely have approved of this 21st century

embodiment of his vision for Adelaide.

Adelaide Central Markets:

having taken a number of photos around Victoria

Square, we crossed King William Street and the tram-tracks to the Central Markets just into Grote Street

(see left). First impressions of the covered market were of it being the biggest

area of market stalls ever seen (Photo

29: Central Market). Rather bemused by the bustle, we wandered along

the rows of stalls. There were vastly stocked fruit

Rundle Mall: crossing the busy street, we rounded off our market lunch

with a Cooper's beer at a pub opposite. Walking back to King William Street, we

passed the offices of SA's Amnesty International, where a poster promoted a

Sorry Day, making an apologetic political statement for all the wrongs inflicted

on

Seeing the Sturt's Desert Pea, albeit in the cultivated setting of the Botanic Gardens, was a suitable climax of our initial four days getting to know a little of Adelaide, and a prelude of things to come as we now head north into the outback of South Australia. We were looking forward to the next phase of the trip, with a few days travel up to the Flinders Ranges mountains, which will be covered in the next edition to be published shortly. Next edition from the South Australian outback to be published soon

|

BACK-PACKING

TRIP TO AUSTRALIA 2011 - Adelaide, South Australia:

BACK-PACKING

TRIP TO AUSTRALIA 2011 - Adelaide, South Australia: Relieved of our packs, we were able to walk

along to the far end of the terminal building to visit the Qantas Historical

Exhibition; here we were greeted by a replica of an Avro biplane, the very first

airplane operated by Qantas in its formative years of 1920~21 (see above left).

This was an impressive display of model aircraft, documents and

memorabilia portraying the proud history of one of the world's longest

established airlines, from its early foundation in 1920~21 by two former RAAF

WW1 pilots, who foresaw the significance of air travel in the development of

Australia. The first flights using an Avro biplane were between Queensland and

Northern Territory, hence the company's name, Queensland and Northern Territory

Aerial Services (QANTAS). The displays traced the developing aircraft used by

the company and the gradually expanding range of routes from the earliest times

using WW1 biplanes, into today's world-wide services flying modern jet airliners, right up to the 380 Airbus

in which we should be flying on our return

legs from Perth~Singapore and back to London Heathrow.

Relieved of our packs, we were able to walk

along to the far end of the terminal building to visit the Qantas Historical

Exhibition; here we were greeted by a replica of an Avro biplane, the very first

airplane operated by Qantas in its formative years of 1920~21 (see above left).

This was an impressive display of model aircraft, documents and

memorabilia portraying the proud history of one of the world's longest

established airlines, from its early foundation in 1920~21 by two former RAAF

WW1 pilots, who foresaw the significance of air travel in the development of

Australia. The first flights using an Avro biplane were between Queensland and

Northern Territory, hence the company's name, Queensland and Northern Territory

Aerial Services (QANTAS). The displays traced the developing aircraft used by

the company and the gradually expanding range of routes from the earliest times

using WW1 biplanes, into today's world-wide services flying modern jet airliners, right up to the 380 Airbus

in which we should be flying on our return

legs from Perth~Singapore and back to London Heathrow. quickly, especially with the half hour gain in time with transition from the

Eastern to Mid-Australian time zone. As the plane descended on its approach to

Adelaide, we were able to make out something of the Adelaide Hills with their

covering of vines. The plane taxied around to its standing, and

quickly, especially with the half hour gain in time with transition from the

Eastern to Mid-Australian time zone. As the plane descended on its approach to

Adelaide, we were able to make out something of the Adelaide Hills with their

covering of vines. The plane taxied around to its standing, and as we came up

the ramp, there was our daughter waiting to greet us. Photos were taken in the

airport lounge after we had recovered our packs from the carousel (

as we came up

the ramp, there was our daughter waiting to greet us. Photos were taken in the

airport lounge after we had recovered our packs from the carousel ( Early history of Adelaide's settlement as a

free colony:

before this trip, we knew little or nothing about the history and topography of

Adelaide or South Australia. Prior to European settlement, the Adelaide plains were inhabited by the Kaurna tribe whose territory extended from what is now

Cape Jervis in the south to the northern end of the Spencer Gulf (see right). By the time

European settlers arrived in 1836, Kaurna population numbers had been decimated by

devastating smallpox and typhoid epidemics which spread from NSW along the Murray River. British

navigator and cartographer Matthew Flinders (see left) and French Captain Nicolas Baudin independently charted

the southern coast of the Australian continent

in 1802~03. In 1830 Charles Sturt (see below right) explored the Murray River, and

reported favourably on the

area now occupied by Adelaide. Captain Collett Barker explored the inlet later

known as the Port Adelaide River, and conducted a more thorough survey of the

area in 1831. On the basis of this, Sturt concluded that this area held promise

as the site for a colony on the coast of South Australia with fresh water and fertile soil for

agriculture.

Early history of Adelaide's settlement as a

free colony:

before this trip, we knew little or nothing about the history and topography of

Adelaide or South Australia. Prior to European settlement, the Adelaide plains were inhabited by the Kaurna tribe whose territory extended from what is now

Cape Jervis in the south to the northern end of the Spencer Gulf (see right). By the time

European settlers arrived in 1836, Kaurna population numbers had been decimated by

devastating smallpox and typhoid epidemics which spread from NSW along the Murray River. British

navigator and cartographer Matthew Flinders (see left) and French Captain Nicolas Baudin independently charted

the southern coast of the Australian continent

in 1802~03. In 1830 Charles Sturt (see below right) explored the Murray River, and

reported favourably on the

area now occupied by Adelaide. Captain Collett Barker explored the inlet later

known as the Port Adelaide River, and conducted a more thorough survey of the

area in 1831. On the basis of this, Sturt concluded that this area held promise

as the site for a colony on the coast of South Australia with fresh water and fertile soil for

agriculture.

Surveyor-General Colonel William Light

(see below right) was

commissioned to identify and survey a site for the new colony, with

harbour, arable land, fresh water, ready communications, building

materials, and free of flood, drought, and disease risk. He had to work quickly

as the settlers were impatient to take possession of the land they had purchased. Despite pressured opposition from Governor Hindmarsh who

favoured a site at Encounter Bay close to the Murray river-mouth, Light selected

gently rising ground spanning the Torrens River valley as being the most

favourable site for the new colony. Light completed his survey by March 1837, a

remarkable achievement, producing a city

plan which carefully fitted the topography of the area: the Torrens Valley was

reserved as open green parklands, with

space for public buildings such as Government House, public cemetery and botanic

gardens; residential areas

Surveyor-General Colonel William Light

(see below right) was

commissioned to identify and survey a site for the new colony, with

harbour, arable land, fresh water, ready communications, building

materials, and free of flood, drought, and disease risk. He had to work quickly

as the settlers were impatient to take possession of the land they had purchased. Despite pressured opposition from Governor Hindmarsh who

favoured a site at Encounter Bay close to the Murray river-mouth, Light selected

gently rising ground spanning the Torrens River valley as being the most

favourable site for the new colony. Light completed his survey by March 1837, a

remarkable achievement, producing a city

plan which carefully fitted the topography of the area: the Torrens Valley was

reserved as open green parklands, with

space for public buildings such as Government House, public cemetery and botanic

gardens; residential areas were planned on higher ground to the north and south

of the river. The central area of the city

was laid out on a grid pattern of streets with the central square (later named

Victoria Square) as focal point and four smaller squares.

were planned on higher ground to the north and south

of the river. The central area of the city

was laid out on a grid pattern of streets with the central square (later named

Victoria Square) as focal point and four smaller squares. Despite being

Despite being

recalled

and replaced as Governor by Captain George Grey, Gawler had put Adelaide on a

firm footing, making South Australia agriculturally self-sufficient. The

colony's finances were rescued by the discovery of silver deposits at Glen

Osmond in 1841 and of copper at Kapunda and Burra in 1842~45. With better

harvests and expanding agriculture, Adelaide began to export meat, wool, wine,

fruit and wheat. It was important for South Australia to

develop trade links with Victoria and New South Wales, but overland transport

was too difficult. Steamboat navigation of the Murray and Darling river systems began

to develop in the 1850~60s, and the first railways in the State were

built in 1854 between Goolwa and Port Elliot to allow freight to be transferred

between Murray River paddle steamers and seagoing vessels. A railway line

linking the harbour at Port Adelaide to the city was completed in 1856, and branch lines in the northern mining towns of Kapunda and

Burra were linked through to the Adelaide metropolitan system. From here, a

southern main line extended to link the Victor Harbour horse tramway to Strathalbyn,

and onwards to the Victoria Border. South Australia became a self-governing

colony in 1856 with the ratification of a new constitution by the British

parliament. Secret ballots were introduced, and a bicameral State Parliament

was elected in March 1857, by which time South Australia had 109,917

inhabitants. In 1860 Adelaide's first reservoir was built, finally providing a more reliable alternative

fresh water source to the turbid River Torrens.

recalled

and replaced as Governor by Captain George Grey, Gawler had put Adelaide on a

firm footing, making South Australia agriculturally self-sufficient. The

colony's finances were rescued by the discovery of silver deposits at Glen

Osmond in 1841 and of copper at Kapunda and Burra in 1842~45. With better

harvests and expanding agriculture, Adelaide began to export meat, wool, wine,

fruit and wheat. It was important for South Australia to

develop trade links with Victoria and New South Wales, but overland transport

was too difficult. Steamboat navigation of the Murray and Darling river systems began

to develop in the 1850~60s, and the first railways in the State were

built in 1854 between Goolwa and Port Elliot to allow freight to be transferred

between Murray River paddle steamers and seagoing vessels. A railway line

linking the harbour at Port Adelaide to the city was completed in 1856, and branch lines in the northern mining towns of Kapunda and

Burra were linked through to the Adelaide metropolitan system. From here, a

southern main line extended to link the Victor Harbour horse tramway to Strathalbyn,

and onwards to the Victoria Border. South Australia became a self-governing

colony in 1856 with the ratification of a new constitution by the British

parliament. Secret ballots were introduced, and a bicameral State Parliament

was elected in March 1857, by which time South Australia had 109,917

inhabitants. In 1860 Adelaide's first reservoir was built, finally providing a more reliable alternative

fresh water source to the turbid River Torrens.

A first visit to Adelaide Botanic Gardens:

until the weekend, our daughter would be working, leaving us to begin our

exploration of Adelaide on our own. The following morning therefore, we set off for our first day

in the

city. Even

though central Adelaide was laid out, from the time of its 1836 foundation, on a

grid pattern with intervening open green spaces and parkland

(

A first visit to Adelaide Botanic Gardens:

until the weekend, our daughter would be working, leaving us to begin our

exploration of Adelaide on our own. The following morning therefore, we set off for our first day

in the

city. Even

though central Adelaide was laid out, from the time of its 1836 foundation, on a

grid pattern with intervening open green spaces and parkland

(

were full of

exotic native Australian bird species; we noted Australian Magpies, a Magpie

Lark, and more Rainbow Lorikeets (

were full of

exotic native Australian bird species; we noted Australian Magpies, a Magpie

Lark, and more Rainbow Lorikeets ( a tram northwards

(

a tram northwards

( Metro Information Centre. We

also paused to admire and photograph some of the older Art Deco buildings, now

dwarfed by modern towering office blocks (see left). The staff at the Metro

Information Centre were most helpful, answering our questions about travel on

the Adelaide metro and bus systems, and providing details of the tram service to Glenelg,

and the free circular bus service. Armed with

all of this, we set off again northwards (or as Paul in his confused delusion

kept insisting, southwards!) along King William Street. Just around the

corner in Rundle Mall, Sheila tried unsuccessfully at the ABC Bookshop for books on

South Australian flora. The TIC kiosk manned by volunteers was also helpful,

answering our further questions and providing copies of the Adelaide

street plan.

Metro Information Centre. We

also paused to admire and photograph some of the older Art Deco buildings, now

dwarfed by modern towering office blocks (see left). The staff at the Metro

Information Centre were most helpful, answering our questions about travel on

the Adelaide metro and bus systems, and providing details of the tram service to Glenelg,

and the free circular bus service. Armed with

all of this, we set off again northwards (or as Paul in his confused delusion

kept insisting, southwards!) along King William Street. Just around the

corner in Rundle Mall, Sheila tried unsuccessfully at the ABC Bookshop for books on

South Australian flora. The TIC kiosk manned by volunteers was also helpful,

answering our further questions and providing copies of the Adelaide

street plan. possible, we learned, by joining one of the organised tours which were held at

10-00am and 2-00pm. Since it was by now only 12-15, we should have to return later; in the meantime

we should catch the free circular bus along North Terrace. The problem

then was to find a bus stop. We asked a lady who gave every appearance of being

local; she apologised for being unfamiliar with Adelaide buses, explaining she

was the president of the SA RSPCA

possible, we learned, by joining one of the organised tours which were held at

10-00am and 2-00pm. Since it was by now only 12-15, we should have to return later; in the meantime

we should catch the free circular bus along North Terrace. The problem

then was to find a bus stop. We asked a lady who gave every appearance of being

local; she apologised for being unfamiliar with Adelaide buses, explaining she

was the president of the SA RSPCA and about to meet with a government minister

(though how this excused her evident lack of knowledge about Adelaide's public transport

system, we never did find out!). She did suggest however there was likely to be

a stop just along at the Railway Station, and just then a bus fortunately drew in.

and about to meet with a government minister

(though how this excused her evident lack of knowledge about Adelaide's public transport

system, we never did find out!). She did suggest however there was likely to be

a stop just along at the Railway Station, and just then a bus fortunately drew in. South Australian State Parliament: the

free bus took us back along North Terrace to the Railway Station, where Paul

admired the station architecture and photographed the impressive arched and coffered ceiling of the concourse

(see above left), while

Sheila raided a leaflet stand. Along at the State

South Australian State Parliament: the

free bus took us back along North Terrace to the Railway Station, where Paul

admired the station architecture and photographed the impressive arched and coffered ceiling of the concourse

(see above left), while

Sheila raided a leaflet stand. Along at the State Parliament, we were again helpfully

received, passing through

security to be signed in. There were only 3 others on

the visit (we had feared the dreaded school parties), and the guide took us through

the 'Members only' doors into the Chamber of the Lower House of the bicameral

parliament, the House of Assembly (

Parliament, we were again helpfully

received, passing through

security to be signed in. There were only 3 others on

the visit (we had feared the dreaded school parties), and the guide took us through

the 'Members only' doors into the Chamber of the Lower House of the bicameral

parliament, the House of Assembly ( The 1856 South Australian

Constitution established the State's bicameral parliament. Initially suffrage

was open to the entire male

population, including aboriginals, with no property

qualification. In 1894 South Australian women were granted the right to vote,

and SA was the first country in the world to allow

The 1856 South Australian

Constitution established the State's bicameral parliament. Initially suffrage

was open to the entire male

population, including aboriginals, with no property

qualification. In 1894 South Australian women were granted the right to vote,

and SA was the first country in the world to allow women to stand as MPs

(Finland followed suit in 1906). Following the world's first secret ballot, the

SA State Parliament met for the first time in 1857. The Governor, representing

the Queen as Australian Head of State, endorses Acts of legislation after bills

have passed through both the House of Assembly and the Upper House, the

Legislative Council.

women to stand as MPs

(Finland followed suit in 1906). Following the world's first secret ballot, the

SA State Parliament met for the first time in 1857. The Governor, representing

the Queen as Australian Head of State, endorses Acts of legislation after bills

have passed through both the House of Assembly and the Upper House, the

Legislative Council. various

tiers of government. The answer to the

first part of the question was that the Federal Senate and House of

Representatives in Canberra dealt with national issues of defence, immigration,

taxation and pensions, while the State has responsibility for education, health,

transport and justice; but no satisfactory response was given about tensions

over degree of delegation and overlap. Again we had been received hospitably at

the SA State

various

tiers of government. The answer to the

first part of the question was that the Federal Senate and House of

Representatives in Canberra dealt with national issues of defence, immigration,

taxation and pensions, while the State has responsibility for education, health,

transport and justice; but no satisfactory response was given about tensions

over degree of delegation and overlap. Again we had been received hospitably at

the SA State Parliament, and the visit was thoroughly instructive as in NSW.

Back at the entrance foyer, we thanked the officials for their openness, and

one of them presented us with souvenir bags; we had feared another

heavy, glossy book!

Parliament, and the visit was thoroughly instructive as in NSW.

Back at the entrance foyer, we thanked the officials for their openness, and

one of them presented us with souvenir bags; we had feared another

heavy, glossy book! William

Street, we waited there for the tram which ran the 10kms out to

William

Street, we waited there for the tram which ran the 10kms out to Glenelg (see above

right). Beyond the central area of the city, the tramline became more of a

suburban railway, running along its sectioned-off trackway and crossing streets

at level crossings through the city's outer suburbs, all the way to the coast

at Glenelg. During the journey, we got into conversation with a retired couple

on holiday here from Melbourne; they urged us simply to make reference on public

transport to our

senior passes without actually showing them or mentioning that they were

non-Australian, to ensure we got seniors' discounts! The tramway terminated at Moseley Square

right by Glenelg's jetty and Town Hall (

Glenelg (see above

right). Beyond the central area of the city, the tramline became more of a

suburban railway, running along its sectioned-off trackway and crossing streets

at level crossings through the city's outer suburbs, all the way to the coast

at Glenelg. During the journey, we got into conversation with a retired couple

on holiday here from Melbourne; they urged us simply to make reference on public

transport to our

senior passes without actually showing them or mentioning that they were

non-Australian, to ensure we got seniors' discounts! The tramway terminated at Moseley Square

right by Glenelg's jetty and Town Hall ( exploration had opened up the territory, along with the great and good who

exploration had opened up the territory, along with the great and good who

invested in and profited from the colony's foundation. It also made passing

reference to the poor, nameless settlers whose suffering ensured the early

colony's success. The plagiarism of Wren's epitaph in St Paul's (Si monumentum

requiris, circumspice) inscribed on the memorial seemed a monumentally

disingenuous piece of hypocrisy, especially when you looked around at Glenelg!

invested in and profited from the colony's foundation. It also made passing

reference to the poor, nameless settlers whose suffering ensured the early

colony's success. The plagiarism of Wren's epitaph in St Paul's (Si monumentum

requiris, circumspice) inscribed on the memorial seemed a monumentally

disingenuous piece of hypocrisy, especially when you looked around at Glenelg! colony would be overrun by mosquito-borne disease, in favour of what he

considered the healthier inland position on the Torrens River plain where he

succeeded in locating his planned grid-layout city with its broad parklands and

open space.

colony would be overrun by mosquito-borne disease, in favour of what he

considered the healthier inland position on the Torrens River plain where he

succeeded in locating his planned grid-layout city with its broad parklands and

open space. fish, supplemented with an extra calamari

ring, all of which we took back to eat at a picnic

fish, supplemented with an extra calamari

ring, all of which we took back to eat at a picnic

table in the square (

table in the square ( This was the historic location where

Governor Hindmarsh had on 28 December 1836 read the Act of Proclamation, though

why he should have chosen to perform this memorable ceremony in the middle of a

housing estate, however des-res, remains a mystery. Afterwards he returned to

the relative luxury of his ship, leaving the forlorn would-be colonists to sweat

it out in temperatures of 40ºC with no shelter yet built. A ceremony is held at

the site on Proclamation Day each year, with the current Governor reading out

Hindmarsh's original speech. Beside the conserved tree remains, a commemorative

plaque from 1857 recorded the 21st anniversary celebrations of the South Australian

colony's foundation (see above left). Every few minutes, large planes

roared surrealistically over the rooftops on their landing approach to Adelaide

airport just a couple of kms away. We took our photos of

the historic site, and returned along MacFarlane Street where in a few minutes a

bus came along. The bus driver

confirmed he could drop us at Jetty Street, and declined to take a fare payment,

simply indicating 'Aah, just get in' in typically brusque Aussie manner.

Back at Jetty Street we had time to relax for a few minutes with a beer at a

street-front bar, as two obviously looking aboriginals, the first we had

noticed, shuffled forlornly by. Another tram drew into the Mosely Square terminus, and we

caught this back to Adelaide city centre.

This was the historic location where

Governor Hindmarsh had on 28 December 1836 read the Act of Proclamation, though

why he should have chosen to perform this memorable ceremony in the middle of a

housing estate, however des-res, remains a mystery. Afterwards he returned to

the relative luxury of his ship, leaving the forlorn would-be colonists to sweat

it out in temperatures of 40ºC with no shelter yet built. A ceremony is held at

the site on Proclamation Day each year, with the current Governor reading out

Hindmarsh's original speech. Beside the conserved tree remains, a commemorative

plaque from 1857 recorded the 21st anniversary celebrations of the South Australian

colony's foundation (see above left). Every few minutes, large planes

roared surrealistically over the rooftops on their landing approach to Adelaide

airport just a couple of kms away. We took our photos of

the historic site, and returned along MacFarlane Street where in a few minutes a

bus came along. The bus driver

confirmed he could drop us at Jetty Street, and declined to take a fare payment,

simply indicating 'Aah, just get in' in typically brusque Aussie manner.

Back at Jetty Street we had time to relax for a few minutes with a beer at a

street-front bar, as two obviously looking aboriginals, the first we had

noticed, shuffled forlornly by. Another tram drew into the Mosely Square terminus, and we

caught this back to Adelaide city centre. Victoria Square:

we set out the following morning along to King William Street for a further day

of explorations in the centre of Adelaide. We were by now beginning to know

Victoria Square:

we set out the following morning along to King William Street for a further day

of explorations in the centre of Adelaide. We were by now beginning to know our

way around (

our

way around ( laid out; we should visit

laid out; we should visit the statue later in our visit.

the statue later in our visit. was first flown at a land rights rally in Victoria Square in

1971, and now flies permanently alongside the Australian National flag at the square

(see above right)

(

was first flown at a land rights rally in Victoria Square in

1971, and now flies permanently alongside the Australian National flag at the square

(see above right)

( Dear Old Queen Victoria's statue, erected in 1894, graced the

central lawned area (see left) (

Dear Old Queen Victoria's statue, erected in 1894, graced the

central lawned area (see left) ( along with a

commemorative plaque by then Minister of Lands in 1989, the Survey Mark is the

reference point for all other survey marks in South Australia.

along with a

commemorative plaque by then Minister of Lands in 1989, the Survey Mark is the

reference point for all other survey marks in South Australia. and vegetable stalls, bread and cheese

stalls (see right), and butchery stalls, but most impressive of all, a fish stall seemingly

kept by Greeks and stocked with every kind of fish

from the Southern Ocean, together with huge prawns, both cooked and raw (

and vegetable stalls, bread and cheese

stalls (see right), and butchery stalls, but most impressive of all, a fish stall seemingly

kept by Greeks and stocked with every kind of fish

from the Southern Ocean, together with huge prawns, both cooked and raw ( the aisles of stalls in Adelaide's wonderful Central Markets was for us one of

most enjoyable experiences of our time in Australia: the multi-origins and

cultures of all the many and varied emigrants to South Australia were reflected in the vibrant variety of

market produce.

the aisles of stalls in Adelaide's wonderful Central Markets was for us one of

most enjoyable experiences of our time in Australia: the multi-origins and

cultures of all the many and varied emigrants to South Australia were reflected in the vibrant variety of

market produce. the aboriginal races by white men since the first settlements of the

continent. It was all well-meant, but seemed somehow overwhelmingly too little,

too late. We hopped on the free tram up to the corner of Rundle Mall, where at

the TIC we established the location of Colonel Light's statue on the hillside in

North Adelaide. We also made acquaintance with Rundle Mall's famous four

life-sized bronze pig statues, named Horatio, Oliver, Truffles and Augusta (see

right) (

the aboriginal races by white men since the first settlements of the

continent. It was all well-meant, but seemed somehow overwhelmingly too little,

too late. We hopped on the free tram up to the corner of Rundle Mall, where at

the TIC we established the location of Colonel Light's statue on the hillside in

North Adelaide. We also made acquaintance with Rundle Mall's famous four

life-sized bronze pig statues, named Horatio, Oliver, Truffles and Augusta (see

right) ( Follow-up visit to Adelaide Botanic Gardens:

we hopped aboard a bus at North Terrace, with

another jovial 'Aah just get in' driver, for the short ride along to the gates

of the Botanic Gardens. Here, in the lovely afternoon golden sunshine, we made

another circuit of the gardens,

Follow-up visit to Adelaide Botanic Gardens:

we hopped aboard a bus at North Terrace, with

another jovial 'Aah just get in' driver, for the short ride along to the gates

of the Botanic Gardens. Here, in the lovely afternoon golden sunshine, we made

another circuit of the gardens, seeing Cycads, a mighty Umbrella Tree (Schefflera

actinophylla) (

seeing Cycads, a mighty Umbrella Tree (Schefflera

actinophylla) (