|

BACK-PACKING

TRIP TO AUSTRALIA 2011 - South Australian outback, Flinders Ranges, Clare Valley: BACK-PACKING

TRIP TO AUSTRALIA 2011 - South Australian outback, Flinders Ranges, Clare Valley:

Leaving Adelaide

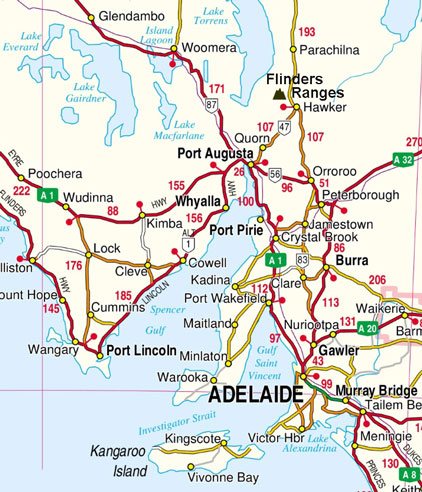

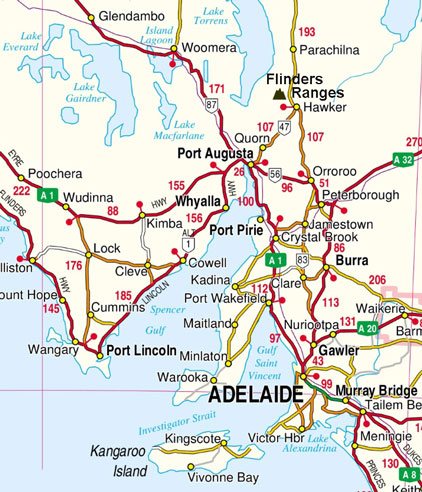

for our trip into South Australian outback: today we were to head north from Adelaide in a

hire-car for our 5 day trip with our daughter Lucy into the South

Australian outback and the Flinders Ranges (see

map right). We were away by 9-00am to drive

around the eastern side of the city and out onto the main road north. Leaving

the city behind, the broad dual-carriageway headed out into flat, rich farming

terrain; this clearly was the produce-growing region serving the city,

filled with market gardens. Traffic was reasonably light and we made good

progress northwards; the sat-nav gave the instruction to go ahead for 262 kms,

and the display showed a single road leading ahead without any side branches

(see left). Leaving Adelaide

for our trip into South Australian outback: today we were to head north from Adelaide in a

hire-car for our 5 day trip with our daughter Lucy into the South

Australian outback and the Flinders Ranges (see

map right). We were away by 9-00am to drive

around the eastern side of the city and out onto the main road north. Leaving

the city behind, the broad dual-carriageway headed out into flat, rich farming

terrain; this clearly was the produce-growing region serving the city,

filled with market gardens. Traffic was reasonably light and we made good

progress northwards; the sat-nav gave the instruction to go ahead for 262 kms,

and the display showed a single road leading ahead without any side branches

(see left).

|

Map of South Australia |

|

This

route was the southern start of the Stuart Highway which crosses Central

Australia from Port Augusta, eventually leading to Alice Springs and finally

Darwin on the north coast of the continent (see left). The only significant traffic were the frequent road-trains of

multiple heavy trucks (Photo 1: Road-trains).

The road ran parallel with the modern Ghan Railway which

carried long freight trains in both directions. After 2 hours' driving and good

progress northwards, we pulled into a truck-stop alongside the road and railway

for a pause, to enjoy a brunch of bacon-egg butty or toasted current bread. For us this was an instructive initial glimpse into Australian

rural life. On the drive up, we had passed through vegetable growing areas of

market gardens, broader, flat prairie lands of cattle and sheep grazing dotted

with farmsteads, and classic open bush-land with just low

vegetation. Occasional roads led off to the side, some tarmaced leading to

signposted towns named in very English manner, others simply dirt roads leading

to farming settlements. This

route was the southern start of the Stuart Highway which crosses Central

Australia from Port Augusta, eventually leading to Alice Springs and finally

Darwin on the north coast of the continent (see left). The only significant traffic were the frequent road-trains of

multiple heavy trucks (Photo 1: Road-trains).

The road ran parallel with the modern Ghan Railway which

carried long freight trains in both directions. After 2 hours' driving and good

progress northwards, we pulled into a truck-stop alongside the road and railway

for a pause, to enjoy a brunch of bacon-egg butty or toasted current bread. For us this was an instructive initial glimpse into Australian

rural life. On the drive up, we had passed through vegetable growing areas of

market gardens, broader, flat prairie lands of cattle and sheep grazing dotted

with farmsteads, and classic open bush-land with just low

vegetation. Occasional roads led off to the side, some tarmaced leading to

signposted towns named in very English manner, others simply dirt roads leading

to farming settlements.

Port Germein's

Jetty, longest in the Southern Hemisphere:

setting off again following the railway, we

passed the insignificant industrial settlement of Port Pirie on the eastern

coast of the Spencer Gulf and dominated by a huge smelter plant. A short distance

further north, we pulled off the main road into Port Germein, set at the

narrowing northern head of the Spencer Gulf (see below right). 219kms north of Adelaide, Port Port Germein's

Jetty, longest in the Southern Hemisphere:

setting off again following the railway, we

passed the insignificant industrial settlement of Port Pirie on the eastern

coast of the Spencer Gulf and dominated by a huge smelter plant. A short distance

further north, we pulled off the main road into Port Germein, set at the

narrowing northern head of the Spencer Gulf (see below right). 219kms north of Adelaide, Port Germein with a current population of just 240 consisted of a single street of

cottages and post-office cum general stores, ending at the 1,532m long jetty which

extended out into the Gulf (Photo 2: Port Germein Jetty). Port Germein's raison d'être clearly had been as an

important transport hub and shipping point for cereals grown in the surrounding

districts of South Australia, following the opening in 1881 of what was once the longest

jetty in the southern hemisphere. Due to the shallow water along the coast, the

long jetty was necessary to allow anchorage for sailing ships to be loaded with grain from

the surrounding hinterland. Bagged wheat was brought in carts from local farms

on

the eastern side of the Southern Flinders Ranges, and in small boats from the west coast

of the Gulf. About 100,000 bags of wheat

each year were loaded into the holds of sailing freighters at the jetties of

South Australian ports like Port Pirie and Port Germaine for transport back to

Europe. We were to see one of these steel-hulled sailing ships, the Pommern, at

Mariehamn in the Åland Islands in 2012: this Glasgow-built merchantman had

operated Germein with a current population of just 240 consisted of a single street of

cottages and post-office cum general stores, ending at the 1,532m long jetty which

extended out into the Gulf (Photo 2: Port Germein Jetty). Port Germein's raison d'être clearly had been as an

important transport hub and shipping point for cereals grown in the surrounding

districts of South Australia, following the opening in 1881 of what was once the longest

jetty in the southern hemisphere. Due to the shallow water along the coast, the

long jetty was necessary to allow anchorage for sailing ships to be loaded with grain from

the surrounding hinterland. Bagged wheat was brought in carts from local farms

on

the eastern side of the Southern Flinders Ranges, and in small boats from the west coast

of the Gulf. About 100,000 bags of wheat

each year were loaded into the holds of sailing freighters at the jetties of

South Australian ports like Port Pirie and Port Germaine for transport back to

Europe. We were to see one of these steel-hulled sailing ships, the Pommern, at

Mariehamn in the Åland Islands in 2012: this Glasgow-built merchantman had

operated

the grain route from South Australia, holding the record for completing

the Roaring Forties home-run around Cape Horn to England in 86 days loaded with

grain. Today we paused here at Port Germein's jetty, taking photos at the pier,

where the low tide left estuary mud along the shore-line shallows of Spencer

Gulf (Photo

3: Spencer Gulf) (see above left). the grain route from South Australia, holding the record for completing

the Roaring Forties home-run around Cape Horn to England in 86 days loaded with

grain. Today we paused here at Port Germein's jetty, taking photos at the pier,

where the low tide left estuary mud along the shore-line shallows of Spencer

Gulf (Photo

3: Spencer Gulf) (see above left).

Australian Arid Lands Botanic Gardens at Port Augusta:

continuing north towards Port Augusta, the road ran along the sandy coastal plain of the

narrowing gulf, edged on the eastern side by the line of hills of the Southern

Flinders. We turned into the town of Port Augusta to find a supermarket for

provisions for Sunday's evening meal, to fill the hire car with fuel, and to get

cash from an ATM. Beyond the town, a short distance up the main Stuart Highway,

we located the

Australian Arid Lands Botanic Gardens.

The Australian Arid Lands Botanic Gardens were established in 1993 to research,

conserve and promote a wider appreciation of Australia’s arid zone flora.

Located on the shores of the Upper Spencer Gulf at Port Augusta, with

spectacular views of the Flinders Ranges, the Gardens are set out with 250

hectares of natural arid zone habitats; these are planted with collections of

Australian flora from those regions of the country with an average annual

rainfall of 300mm or less, the definition of arid lands (Australian average rainfall). Australian Arid Lands Botanic Gardens at Port Augusta:

continuing north towards Port Augusta, the road ran along the sandy coastal plain of the

narrowing gulf, edged on the eastern side by the line of hills of the Southern

Flinders. We turned into the town of Port Augusta to find a supermarket for

provisions for Sunday's evening meal, to fill the hire car with fuel, and to get

cash from an ATM. Beyond the town, a short distance up the main Stuart Highway,

we located the

Australian Arid Lands Botanic Gardens.

The Australian Arid Lands Botanic Gardens were established in 1993 to research,

conserve and promote a wider appreciation of Australia’s arid zone flora.

Located on the shores of the Upper Spencer Gulf at Port Augusta, with

spectacular views of the Flinders Ranges, the Gardens are set out with 250

hectares of natural arid zone habitats; these are planted with collections of

Australian flora from those regions of the country with an average annual

rainfall of 300mm or less, the definition of arid lands (Australian average rainfall).

The Gardens covered a seemingly huge area of

semi-wild scrub-land, with naturally laid-out zones of wild shrubs from the

different regions of SA desert lands

(Photo

4: Arid Lands Botanic Gardens). With the aid of a

commentary-plan from the info-centre, we walked the loop-paths photographing many

of the fascinating specimens of native wild flora (see above left). But for botanic gardens, the

plantings were disappointingly labelled,

and therefore frustratingly difficult

to identify individual species. Having said that however, the desert setting in the warm afternoon

sunshine was hugely impressive (Photo

5: Desert setting), with an occasional gecko scuttling around in the

sand beneath bushes

(Photo

6: Gecko).

We did see further examples of South with an occasional gecko scuttling around in the

sand beneath bushes

(Photo

6: Gecko).

We did see further examples of South Australia's iconic flower, Sturt's Desert

Pea (Swainsona formosa) (Photo

7: Sturt's Desert Pea), this time growing in its natural conditions in dry, red desert

sand.

Typical plants of the arid Australian bush-land included needle-like Hakea

Bushes (Hakea leucoptera), and porcupine-clumps of Spinifex grass (Triodia

scariosa); the brittle tips of these plants' spiny leaves are rich in silica, and if

brushed against easily break off sticking in the skin with risk of infection. We

also found more distinctive arid desert flora: a Cactus Pea bush (Bossiaea walkeri) with

its flattened leaf-like grey-green stems and red pea-type flowers (Photo

8: Cactus Pea), isolated clumps of erect, narrow-leaved shrubs with tall flowering

heads, later identified as a Yakka, also known as Grass Trees (Xanthorrhoea sp) (Photo

9: Grass Tree - Yakka); the Narrawa Burr (Solanum cinereum) with showy

purple flowers and crinkly leaves with viciously large spines along their

mid-vein (Photo

10: Narrawa Burr - Solanum cinereum) (see above right), and a specimen of

Harlequin Mistletoe (Lysiana exocarpi), a shrub endemic to Australia and

parasitic on Acacia and Eucalyptus, with distinctive red tubular flowers and protruding

stamens

(Photo

11: Harlequin Mistletoe). In spite of having seen many Eucalyptus trees so far in

our Australian travels, for the first time now we could examine close up

Eucalyptus flowers and fruit

(see left) (Photo

12: Eucalyptus flowers). We

had the opportunity to complete one of the circuits, particularly admiring the desert plant

life of the Flinders region. But time was moving on and the sun beginning to

lower; we still had another hour's drive north to reach Quorn before dusk, to

avoid risk of encountering kangaroos on the road. Australia's iconic flower, Sturt's Desert

Pea (Swainsona formosa) (Photo

7: Sturt's Desert Pea), this time growing in its natural conditions in dry, red desert

sand.

Typical plants of the arid Australian bush-land included needle-like Hakea

Bushes (Hakea leucoptera), and porcupine-clumps of Spinifex grass (Triodia

scariosa); the brittle tips of these plants' spiny leaves are rich in silica, and if

brushed against easily break off sticking in the skin with risk of infection. We

also found more distinctive arid desert flora: a Cactus Pea bush (Bossiaea walkeri) with

its flattened leaf-like grey-green stems and red pea-type flowers (Photo

8: Cactus Pea), isolated clumps of erect, narrow-leaved shrubs with tall flowering

heads, later identified as a Yakka, also known as Grass Trees (Xanthorrhoea sp) (Photo

9: Grass Tree - Yakka); the Narrawa Burr (Solanum cinereum) with showy

purple flowers and crinkly leaves with viciously large spines along their

mid-vein (Photo

10: Narrawa Burr - Solanum cinereum) (see above right), and a specimen of

Harlequin Mistletoe (Lysiana exocarpi), a shrub endemic to Australia and

parasitic on Acacia and Eucalyptus, with distinctive red tubular flowers and protruding

stamens

(Photo

11: Harlequin Mistletoe). In spite of having seen many Eucalyptus trees so far in

our Australian travels, for the first time now we could examine close up

Eucalyptus flowers and fruit

(see left) (Photo

12: Eucalyptus flowers). We

had the opportunity to complete one of the circuits, particularly admiring the desert plant

life of the Flinders region. But time was moving on and the sun beginning to

lower; we still had another hour's drive north to reach Quorn before dusk, to

avoid risk of encountering kangaroos on the road.

Over the Pichi Richi Pass to Quorn: returning to Port Augusta, the

sat-nav directed us onto the more minor road which followed the course of the

Pichi Richi Railway over a shoulder of the Flinders Hills. After a pause for an

Aussie souvenir photo by a road-side kangaroo warning sign (see left), we continued on the winding road

over the Pichi Richi Pass alongside the railway in the late afternoon sunlight.

It was glorious bush-land terrain, covered with scrub and eucalyptus and lit by golden sunlight

(Photo

13: Pichi Richi Pass) (see right). By 5-00pm, we

reached the one-street outback town of Quorn to find tonight's accommodation, the

Austral pub-motel

(Photo

14: Austral pub, Quorn) just opposite the Pichi Richi Railway station. The

pub frontage and line of

the street was like something out of the Wild West, and we happily fell into the

bar to book in. Our motel room around the back was functionally adequate if

rather basic, and having stowed our kit, we returned to the bar to settle in for

schooners of Amber and Coopers after such a long and wearying drive and our

memorable afternoon in SA outback sunshine at the Arid Lands Botanic Gardens. And to round off the day, we enjoyed an excellent

supper of tender, juicy kangaroo steaks with an unusual range of Aussie

vegetables, a superbly memorable evening. Paul stayed on to watch Aussie Rules

Football on the bar TV with a last glass of Amber, and a Pom's tutorial session

from the landlady on the curious rules of AFL, before turning in himself.

It was glorious bush-land terrain, covered with scrub and eucalyptus and lit by golden sunlight

(Photo

13: Pichi Richi Pass) (see right). By 5-00pm, we

reached the one-street outback town of Quorn to find tonight's accommodation, the

Austral pub-motel

(Photo

14: Austral pub, Quorn) just opposite the Pichi Richi Railway station. The

pub frontage and line of

the street was like something out of the Wild West, and we happily fell into the

bar to book in. Our motel room around the back was functionally adequate if

rather basic, and having stowed our kit, we returned to the bar to settle in for

schooners of Amber and Coopers after such a long and wearying drive and our

memorable afternoon in SA outback sunshine at the Arid Lands Botanic Gardens. And to round off the day, we enjoyed an excellent

supper of tender, juicy kangaroo steaks with an unusual range of Aussie

vegetables, a superbly memorable evening. Paul stayed on to watch Aussie Rules

Football on the bar TV with a last glass of Amber, and a Pom's tutorial session

from the landlady on the curious rules of AFL, before turning in himself.

Our day on the Pichi Richi Heritage Railway: we were up early to complete yesterday's log and to get breakfast over in the pub, in

order to be over at the station (see below left) for a good seat on the train. We had

booked

our tickets on-line for our ride on the preserved

Pichi Richi Heritage Railway,

but seats on the train were on a first-come-first-served basis, and a number of

folk were gathering early. The steam locomotive brought in the vintage wooden

coaches then returned to the depot; we

browsed the souvenir shop, waiting for

10-00am when we could board the train to reserve our seats. browsed the souvenir shop, waiting for

10-00am when we could board the train to reserve our seats.

History of the Ghan Railway: construction

had started in 1878 on the 3'6'' narrow gauge Port Augusta and Government Gums

(now known as Farina, north of the Flinders Ranges) Railway. Quorn, named after

the Leicestershire village, grew up as a small outback railhead town around the

railway which reached the town from Port Augusta in 1879. The line was extended

in 1891 to Oodnadatta, and to Alice Springs 1,241 km further

north into the interior in 1929, establishing a crucial rail link into Central Australia.

The Old Ghan, as the Great Northern Railway was

called (allegedly from the Asian camel drivers or Afghans who worked on the

line's construction), served all the outback towns on the journey northwards

into the interior to Alice Springs. The current elegant stone-and brick-built

Quorn station was completed in 1916. Quorn's hotels and pubs provided

accommodation for passengers as a staging halt on the days-long railway journey.

In 1917, Quorn became the rail travel crossroads in Australia, when the

east~west Trans-Australian Railway was completed across the Nullarbor Plain

linking Port Augusta to Kalgoorlie in Western Australia. This made Quorn

an

important town, given that people an

important town, given that people travelling by rail both east~west or

south~north in Australia would need to pass through Quorn. As a result, many

fine buildings were built as the town prospered and expanded. During WW2, Quorn

became an assembly area in the movement of troops and supplies to Darwin in

readiness to repel the threat of Japanese invasion following the 1941 bombing,

and for the transport of evacuees south. After the war, business in Quorn

declined, particularly after the new standard gauge Ghan west of the Flinders

was completed in 1956 (see map of Ghan Railway), and the Old Ghan narrow

gauge line closed in 1970. The Pichi Richi

Preservation Society re-opened the line in 1973 from Quorn southwards to Port Augusta over

the Pichi Richi Pass through Woolshed Flat, following the route of the original

3' 6” narrow gauge Old Ghan.

travelling by rail both east~west or

south~north in Australia would need to pass through Quorn. As a result, many

fine buildings were built as the town prospered and expanded. During WW2, Quorn

became an assembly area in the movement of troops and supplies to Darwin in

readiness to repel the threat of Japanese invasion following the 1941 bombing,

and for the transport of evacuees south. After the war, business in Quorn

declined, particularly after the new standard gauge Ghan west of the Flinders

was completed in 1956 (see map of Ghan Railway), and the Old Ghan narrow

gauge line closed in 1970. The Pichi Richi

Preservation Society re-opened the line in 1973 from Quorn southwards to Port Augusta over

the Pichi Richi Pass through Woolshed Flat, following the route of the original

3' 6” narrow gauge Old Ghan.

Our ride on the preserved Pichi Richi Railway: the Pichi Richi

Railway now operates weekend steam-hauled services on this southern section of

the Old Ghan route as far as Woolshed Flat and back. The engine pulling

this morning's train, 4-8-2 locomotive number W933, was built by Beyer-Peacock

of Manchester in 1951, initially for the Western Australian State Railway (see

above right). We

secured seats in the end-carriage and managed to open the windows for photography

(Photo

15: Railway photography). At

10‑30am the train pulled out, gaining height gradually on the

1:60 gradient up to Summit at an

elevation of elevation of 406m (see above left), and over the Pichi Richi

Pass (344m)

(Photo

16: Pichi Richi Pass). The outback scenery was magnificent, with the line passing through

grazing country bounded by the scrub-covered, red-brown rocky hills of the Flinders Range

(Photo

17: Flinders Hills). We

all took a number of photos from the train windows, both of the terrain and of the engine

down the curving length of the train amid the Flinders outback hills (see above

right) (Photo

18: Curving length of train). Over the Summit, the line descended

via tight curves through more wooded terrain with beautifully shaped,

silver-coloured Eucalyptus, down into the siding at Woolshed Flat for a 40

minute break (see left); while other passengers took refreshments, we

photographed the engine as it ran around the train, and examined the wildlife. The ground around Woolshed

Flat was covered with tiny snails and wild gourds, and before re-boarding the train,

we had to inspect one another's boots and carefully pick off the sharp, prickly

fruiting burs. On the return journey, again many photos were taken around the

curving length of the train, with the engine now working hard up the steep grade

of the pass (Photo

19: Working hard up grade) (see right). On the return ride we saw more of the

Grass-trees (Xanthorrhoea), first seen yesterday at the Arid Lands Botanic Gardens,

growing across the open hill-side (Photo

20: Yakkas - Xanthorrhoea); fellow

passengers called these Yakkas, or more colloquially Blackboys from their tall

flowering heads sprouting from the mop of grass-leaves which were said to resemble

Aboriginals carrying spears. Back at Quorn, souvenir photos were taken of the steam locomotive to recall our ride on this preserved section of the Old Ghan Railway

(Photo

21: 4-8-2 locomotive W933). 406m (see above left), and over the Pichi Richi

Pass (344m)

(Photo

16: Pichi Richi Pass). The outback scenery was magnificent, with the line passing through

grazing country bounded by the scrub-covered, red-brown rocky hills of the Flinders Range

(Photo

17: Flinders Hills). We

all took a number of photos from the train windows, both of the terrain and of the engine

down the curving length of the train amid the Flinders outback hills (see above

right) (Photo

18: Curving length of train). Over the Summit, the line descended

via tight curves through more wooded terrain with beautifully shaped,

silver-coloured Eucalyptus, down into the siding at Woolshed Flat for a 40

minute break (see left); while other passengers took refreshments, we

photographed the engine as it ran around the train, and examined the wildlife. The ground around Woolshed

Flat was covered with tiny snails and wild gourds, and before re-boarding the train,

we had to inspect one another's boots and carefully pick off the sharp, prickly

fruiting burs. On the return journey, again many photos were taken around the

curving length of the train, with the engine now working hard up the steep grade

of the pass (Photo

19: Working hard up grade) (see right). On the return ride we saw more of the

Grass-trees (Xanthorrhoea), first seen yesterday at the Arid Lands Botanic Gardens,

growing across the open hill-side (Photo

20: Yakkas - Xanthorrhoea); fellow

passengers called these Yakkas, or more colloquially Blackboys from their tall

flowering heads sprouting from the mop of grass-leaves which were said to resemble

Aboriginals carrying spears. Back at Quorn, souvenir photos were taken of the steam locomotive to recall our ride on this preserved section of the Old Ghan Railway

(Photo

21: 4-8-2 locomotive W933).

Collecting the hire-car, we set off

northwards on this afternoon's venture to drive outback dirt roads heading

towards tonight's goal of Hawker. Collecting the hire-car, we set off

northwards on this afternoon's venture to drive outback dirt roads heading

towards tonight's goal of Hawker.

Into the SA outback at Dutchman's Stern and Warren Gorge:

crossing the railway and turning north from Quorn onto back-roads, the gravel surface was good.

We

headed

inland through groves of gum trees to turn off again onto a narrow side-lane detour

leading to the conservation area of The Dutchman's Stern; this was named by the British

navigator Matthew Flinders after a prominent 820m high bluff shaped like the

stern of an 18th century Dutch sailing ship (see left) (Photo

22 - Dutchman's Stern). Time however was pressing, and

further exploration was limited to photos from the viewpoint.

Returning to the principal dirt road, we continued

northwards along Arden Vale. Groves of gum trees lined the road, with the creeks

totally dry at this time of year. At Warren Gorge we turned off again for a

short distance to a small wild camping area in a grove of old, gnarled gum

trees (Photo

23 - Warren Gorge Gum trees), an astonishingly beautiful spot with jagged, bright orange rock

formations giving a stunning contrast with the clear blue sky and dark Cypress

Pines, and pink and grey Galah cockatoos squawking in the branches off

Eucalyptus trees (see right). conservation area of The Dutchman's Stern; this was named by the British

navigator Matthew Flinders after a prominent 820m high bluff shaped like the

stern of an 18th century Dutch sailing ship (see left) (Photo

22 - Dutchman's Stern). Time however was pressing, and

further exploration was limited to photos from the viewpoint.

Returning to the principal dirt road, we continued

northwards along Arden Vale. Groves of gum trees lined the road, with the creeks

totally dry at this time of year. At Warren Gorge we turned off again for a

short distance to a small wild camping area in a grove of old, gnarled gum

trees (Photo

23 - Warren Gorge Gum trees), an astonishingly beautiful spot with jagged, bright orange rock

formations giving a stunning contrast with the clear blue sky and dark Cypress

Pines, and pink and grey Galah cockatoos squawking in the branches off

Eucalyptus trees (see right).

Willochra

Plain and Goyder's Line: continuing north, the gum trees were left

behind as we passed into the wide, open terrain of Willochra Plain, the name Willochra being derived from an Aboriginal word meaning Flooded creek where wild

bushes grow; the plain is crossed by the large but ephemeral, gum tree-lined Willochra Creek. Much of the plain is semi-arid and drought-affected, lying

north well beyond Goyder's Line, which since 1865 has Willochra

Plain and Goyder's Line: continuing north, the gum trees were left

behind as we passed into the wide, open terrain of Willochra Plain, the name Willochra being derived from an Aboriginal word meaning Flooded creek where wild

bushes grow; the plain is crossed by the large but ephemeral, gum tree-lined Willochra Creek. Much of the plain is semi-arid and drought-affected, lying

north well beyond Goyder's Line, which since 1865 has demarcated the limits of

South Australian lands suitable for arable agricultural settlement, and land

only suitable for pastoralism. In 1865 George Goyder, then SA Surveyor-General,

was commissioned to map the boundary between those areas of the new colony that

benefitted from sufficient annual rainfall to support arable farming

particularly for wheat growing, and those

subject to drought. North of Goyder's Line, annual rainfall is less than 10

inches, too low to support crop-growing, the land being only suitable for

stock grazing (see map left). In spite of Goyder's invaluable work, successive

colonial governments of the 1870s and 1880s surveyed and released former livestock

grazing pastoral land

for leasing for crop farming. But many such settlements inevitably failed because of the

arid nature of the drought-prone land, and now tragically stand long-abandoned. The Willochra Plain terrain stretched away to

open horizons in all directions, a frighteningly eerie, empty place, the land

covered with low Mallee scrub. This was cattle and sheep grazing country on

a huge scale, crossed by a network of dry creeks. But the scattered ruins of

forlornly abandoned farms and homesteads told the sad story of failed 19th

century attempts to settle and to farm these arid, inhospitable plains. demarcated the limits of

South Australian lands suitable for arable agricultural settlement, and land

only suitable for pastoralism. In 1865 George Goyder, then SA Surveyor-General,

was commissioned to map the boundary between those areas of the new colony that

benefitted from sufficient annual rainfall to support arable farming

particularly for wheat growing, and those

subject to drought. North of Goyder's Line, annual rainfall is less than 10

inches, too low to support crop-growing, the land being only suitable for

stock grazing (see map left). In spite of Goyder's invaluable work, successive

colonial governments of the 1870s and 1880s surveyed and released former livestock

grazing pastoral land

for leasing for crop farming. But many such settlements inevitably failed because of the

arid nature of the drought-prone land, and now tragically stand long-abandoned. The Willochra Plain terrain stretched away to

open horizons in all directions, a frighteningly eerie, empty place, the land

covered with low Mallee scrub. This was cattle and sheep grazing country on

a huge scale, crossed by a network of dry creeks. But the scattered ruins of

forlornly abandoned farms and homesteads told the sad story of failed 19th

century attempts to settle and to farm these arid, inhospitable plains.

Abandoned settlement of Kanyaka: after

driving some miles across these grazing lands of Willochra Plain (see above

right) (Photo

24: Willochra Plain), we paused at Proby's Grave. Hugh Proby was a Scottish aristocrat who had led the founding of the ill-fated

pastoral farming settlement at Kanyaka in Willochra Plain in 1850; he was

drowned in the swollen Willochra Abandoned settlement of Kanyaka: after

driving some miles across these grazing lands of Willochra Plain (see above

right) (Photo

24: Willochra Plain), we paused at Proby's Grave. Hugh Proby was a Scottish aristocrat who had led the founding of the ill-fated

pastoral farming settlement at Kanyaka in Willochra Plain in 1850; he was

drowned in the swollen Willochra

Creek in 1852 aged 24 during violent rain

storms while trying to recover stampeded cattle. His brother and sister had

shipped out a huge granite slab from Scotland to be engraved with his memorial which now stood here

(see right) (Photo

25: Proby's Grave). Looking around at the arid, scrub-covered endless plains, it seemed

inconceivable to attempt even to rear cattle here let alone to grow wheat. Some distance further, we

reached the junction of Simmonston. It had been proposed to build another

outback town here on what was envisaged as the route of the Ghan Railway

advancing northward from Quorn. Plots of land were sold to prospective settlers

and building began in 1880. But an alternative route east of the Flinders was selected

for the railway; the town of Simmonston died before it was even begun, and the

lonely remains stood here amid the scrub and desolate red earth of Willochra Plains as testimony to the unfortunate

settlers (Photo

26: Site of Simmonston) (see left). Rejoining the main tarmaced road to Hawker, we

continued north crossing a number of now totally dry creeks. We paused at the

aboriginal water hole of Kanyaka amid a rocky grove of gum trees; legend has Creek in 1852 aged 24 during violent rain

storms while trying to recover stampeded cattle. His brother and sister had

shipped out a huge granite slab from Scotland to be engraved with his memorial which now stood here

(see right) (Photo

25: Proby's Grave). Looking around at the arid, scrub-covered endless plains, it seemed

inconceivable to attempt even to rear cattle here let alone to grow wheat. Some distance further, we

reached the junction of Simmonston. It had been proposed to build another

outback town here on what was envisaged as the route of the Ghan Railway

advancing northward from Quorn. Plots of land were sold to prospective settlers

and building began in 1880. But an alternative route east of the Flinders was selected

for the railway; the town of Simmonston died before it was even begun, and the

lonely remains stood here amid the scrub and desolate red earth of Willochra Plains as testimony to the unfortunate

settlers (Photo

26: Site of Simmonston) (see left). Rejoining the main tarmaced road to Hawker, we

continued north crossing a number of now totally dry creeks. We paused at the

aboriginal water hole of Kanyaka amid a rocky grove of gum trees; legend has it that dying

aborigines were laid to rest in the shadow of the great rock overlooking the

water hole. As we walked over to the waterhole, the outback flies were

horrendous. Nearby were the ruined remains of Proby's failed farming settlement

of Kanyaka (Photo

27: Waterhole and settlement of Kanyaka), named after the

waterhole. We wondered what had happened to this and so many it that dying

aborigines were laid to rest in the shadow of the great rock overlooking the

water hole. As we walked over to the waterhole, the outback flies were

horrendous. Nearby were the ruined remains of Proby's failed farming settlement

of Kanyaka (Photo

27: Waterhole and settlement of Kanyaka), named after the

waterhole. We wondered what had happened to this and so many

of the other

failed settlements we had passed during that afternoon. of the other

failed settlements we had passed during that afternoon.

Wonoka sheep station, our accommodation for the Flinders Ranges:

passing Hawker, we turned off further north onto a

dirt road (see right) leading for 7 kms into the bush to the farmstead and sheep station of

Wonoka where we had rented the former sheep-shearer's cottage for the

next two nights. Eventually after a long drive through the scrub-covered

bush-land grazing

grounds, we reached the isolated farmstead, to be greeted by the farmer, Peter

McInnis; we learned that his family had settled the lands in the mid-19th century, originating

from Ireland and the Isle of Mull. He now kept 2,000 head of sheep, all Merinos

with their tough wool, on the 20,000 hectares of land of this lonely

sheep–station. We

settled in to the straightforward former sheep-shearer's cottage, and stood

gazing around in awe at the spectacular views to the surrounding Flinders Hills,

now lit by the last golden light of the setting sun as it disappeared below the

line of hills (see above left) (Photo

28: Wonoka sheep station). We have stayed in some impressively memorable locations during

our travels, but none as isolated and grandiose as this. Today we had at last sampled the real outback

of Australia, and very weary after such a long and eventful day, we cooked

supper of stir-fry with pasta and barbecued corn cobs. With the impressively memorable locations during

our travels, but none as isolated and grandiose as this. Today we had at last sampled the real outback

of Australia, and very weary after such a long and eventful day, we cooked

supper of stir-fry with pasta and barbecued corn cobs. With the

salmon-pink

sunset after-glow now silhouetting trees along the horizon (Photo

29: Sunset after-glow), darkness

fell remarkably quickly at

6-00pm, and as night came on, the sky was lit by a

full moon (see right), with the Southern Cross clearly visible. It was such a peacefully

still evening, disturbed only by the bothersome outback flies and bugs attracted

to the cottage lights; we were thankful for the fly-screens on the doors. salmon-pink

sunset after-glow now silhouetting trees along the horizon (Photo

29: Sunset after-glow), darkness

fell remarkably quickly at

6-00pm, and as night came on, the sky was lit by a

full moon (see right), with the Southern Cross clearly visible. It was such a peacefully

still evening, disturbed only by the bothersome outback flies and bugs attracted

to the cottage lights; we were thankful for the fly-screens on the doors.

North to the Flinders Ranges:

the alarm was set early, just in time to see the morning sun breasting the eastern

hill-side, and flooding the cottage with bright sunshine. We sat out for a hasty

breakfast in these magnificent surroundings

(Photo

30: Breakfast at Wonoka), and were away by

9‑00am, to drive back down the sheep-station dirt track to the main road into

Hawker. The sky was pure blue and the early sun hot; it was a truly beautiful

morning. Hawker, as the cross-roads town of

this northern part of the Flinders Ranges 350 kms north of Adelaide, was just a

small place with 490 population. It also had a number of camping-caravan sites,

a small general stores, bank-ATM, and a couple of filling stations; and that was

about it, other than a Restaurant-Gallery at the Old Ghan railway station which

looked (and surely was) ultra-pseudy and even more ultra-expensive. Having

satisfied ourselves that the general stores had reasonable stocks for supper,

and stayed open until 5-00pm, we pressed on northwards to Wilpena. the Old Ghan railway station which

looked (and surely was) ultra-pseudy and even more ultra-expensive. Having

satisfied ourselves that the general stores had reasonable stocks for supper,

and stayed open until 5-00pm, we pressed on northwards to Wilpena.

As we drove north from Hawker, the open outback

terrain looked forbiddingly attractive in the morning sunshine, backed by the

red sandstone ridges of the Flinders. We paused at the Rawnsley Bluff look-out

with its magnificent views across the outback grazing lands to the

whaleback ridges of the Elder Range (Photo

31: Elder Range) (see above left and right). This was a well-made road and we made good

speed northwards to pull into the Arkaba Hill look-out, again with

wonderful views across to the red sandstone mountains which enclose the southern

bounds of Wilpena Pound lit by the morning sun (see left) (Photo

32: Wilpena Pound southern outer face). Our plan for today was to climb

to one of the lookout points on the rim of Wilpena Pound, but at this stage, it

was difficult to envisage the exact topography of the Pound and its relationship

with the rest of the Northern Flinders; we needed maps. As we drove north from Hawker, the open outback

terrain looked forbiddingly attractive in the morning sunshine, backed by the

red sandstone ridges of the Flinders. We paused at the Rawnsley Bluff look-out

with its magnificent views across the outback grazing lands to the

whaleback ridges of the Elder Range (Photo

31: Elder Range) (see above left and right). This was a well-made road and we made good

speed northwards to pull into the Arkaba Hill look-out, again with

wonderful views across to the red sandstone mountains which enclose the southern

bounds of Wilpena Pound lit by the morning sun (see left) (Photo

32: Wilpena Pound southern outer face). Our plan for today was to climb

to one of the lookout points on the rim of Wilpena Pound, but at this stage, it

was difficult to envisage the exact topography of the Pound and its relationship

with the rest of the Northern Flinders; we needed maps.

Topography and history of farming at Wilpena Pound: Wilpena Pound is a natural oval, bowl-shaped

amphitheatre of sedimentary rock, 17 km long and 8 km wide, in the heart of the

Southern Flinders Range mountains; its huge cattle-pound appearance gave the

geographical feature its name

(Map of Wilpena Pound).

The flat plain enclosed within the basin is covered with scrub and trees, and totally surrounded by jagged

hills which form the amphitheatre rim. This valley surrounded by its rim of

mountains was formed 600 million years ago during the

Southern Flinders Range mountains; its huge cattle-pound appearance gave the

geographical feature its name

(Map of Wilpena Pound).

The flat plain enclosed within the basin is covered with scrub and trees, and totally surrounded by jagged

hills which form the amphitheatre rim. This valley surrounded by its rim of

mountains was formed 600 million years ago during

the Palaeozoic Era by faster

erosion of the valley floor soft bed-rock, compared with the harder sandstone

rocks which form the enclosing cliffs of the Pound. The wall of mountains almost

completely encircles the gently-sloping interior of the Pound, with the only

breaks being the gorge of Wilpena Gap on the eastern side of the range, and the

other leading through the narrow, rocky Edeowie Gorge on the western side; most

of the Pound's inner area drains into Wilpena Creek which exits through Wilpena

Gap. The highest peak in the Pound, also the highest of the Flinders Ranges, is

St Mary Peak (1,171m) on the north-eastern side. the Palaeozoic Era by faster

erosion of the valley floor soft bed-rock, compared with the harder sandstone

rocks which form the enclosing cliffs of the Pound. The wall of mountains almost

completely encircles the gently-sloping interior of the Pound, with the only

breaks being the gorge of Wilpena Gap on the eastern side of the range, and the

other leading through the narrow, rocky Edeowie Gorge on the western side; most

of the Pound's inner area drains into Wilpena Creek which exits through Wilpena

Gap. The highest peak in the Pound, also the highest of the Flinders Ranges, is

St Mary Peak (1,171m) on the north-eastern side.

For 1000s of years, the Adnyamathanha

aboriginals were the only inhabitants of Wilpena Pound; they called the Pound

Ikara, meaning meeting/initiation place. Although the first European to sight

the distant peaks of the Pound was Edward Eyre on his first 1839 expedition to

explore the vicinity of Lake Torrens, Eyre did not actually visit or investigate

these ranges and so had no idea of their geographical formation. Matthew Flinder's botanist Robert Brown had climbed one of the highest peaks of the

southern Flinders in March 1802, but Wilpena would have been beyond his view just over the

horizon. William and John Browne were the first to discover Wilpena Pound in

1850, and realising its prospects for pastoralism, applied to lease the land.

The Browne brothers won the claim for Wilpena, and Henry Strong Price ran the

40,000-hectare Wilpena Station for them, purchasing Wilpena from the Brownes in

1861. Initially, being such a well-protected and isolated natural enclosure, the

Pound was seen as an ideal stock compound used for grazing horses. By 1863 the Wilpena

Estate consisted of well over 200,000 hectares of grazing land, but was almost

ruined by the drought of that decade.

The Pound was leased to the Hill family from

Hawker in 1901. They worked determinedly to clear the valley for wheat growing,

something never before attempted so far north. Goyder's Line had proved accurate

with regard to agricultural expansion during the great drought of the 1880s, and Wilpena is some 140 kilometres (87 mi) north of the Line. But being in the

shadow of some of the highest mountains of the Flinders, rainfall in the Pound

is a little higher. After the immense labour of constructing a road through for wheat growing,

something never before attempted so far north. Goyder's Line had proved accurate

with regard to agricultural expansion during the great drought of the 1880s, and Wilpena is some 140 kilometres (87 mi) north of the Line. But being in the

shadow of some of the highest mountains of the Flinders, rainfall in the Pound

is a little higher. After the immense labour of constructing a road through

the

torturous Wilpena Gap, the Hill family cleared open patches in the thick scrub

of the Pound's interior and built a small homestead, the remains of which can

still be seen today. They harvested their first wheat crop from the Pound in

1902 despite it being a drought year, and for several years they had moderate

success growing crops within the Pound. But in 1914 a major flood destroyed the

road that they had laboured so hard to construct up through the gorge. They

continued to keep horses and cattle in the Pound until the lease expired in 1921

when, defeated in their efforts, they sold their homestead to the government and

the land was abandoned. The Pound then became a forest reserve leased for

grazing, and in 1945 the tourist potential of the area was recognised when a

National Pleasure Resort was opened on the southern side of the creek just

outside the gorge. The Pound later became part of the Flinders Ranges National

Park. the

torturous Wilpena Gap, the Hill family cleared open patches in the thick scrub

of the Pound's interior and built a small homestead, the remains of which can

still be seen today. They harvested their first wheat crop from the Pound in

1902 despite it being a drought year, and for several years they had moderate

success growing crops within the Pound. But in 1914 a major flood destroyed the

road that they had laboured so hard to construct up through the gorge. They

continued to keep horses and cattle in the Pound until the lease expired in 1921

when, defeated in their efforts, they sold their homestead to the government and

the land was abandoned. The Pound then became a forest reserve leased for

grazing, and in 1945 the tourist potential of the area was recognised when a

National Pleasure Resort was opened on the southern side of the creek just

outside the gorge. The Pound later became part of the Flinders Ranges National

Park.

Wilpena Pound National Park Information

Centre for maps and routes: 40kms further north, we crossed the National

Park boundary and paused to pay our $7.50 entry fee. It was noticeable that once

into the protected area of the national park, where the natural vegetation had

been spared from grazing, small pine trees flourished along the road side. We

turned off to the Wilpena National Park Information Centre in search of maps,

details of

the Pound's topography, and for advice on half-day walks. The most suitable

round trip bushwalk, given our limited time, was the Wangara Lookout Walk: this

overall 8 km route would take us up Wilpena Creek via Sliding Rock Gorge, the

only natural access to penetrate the surrounding barrier of hills into the paused to pay our $7.50 entry fee. It was noticeable that once

into the protected area of the national park, where the natural vegetation had

been spared from grazing, small pine trees flourished along the road side. We

turned off to the Wilpena National Park Information Centre in search of maps,

details of

the Pound's topography, and for advice on half-day walks. The most suitable

round trip bushwalk, given our limited time, was the Wangara Lookout Walk: this

overall 8 km route would take us up Wilpena Creek via Sliding Rock Gorge, the

only natural access to penetrate the surrounding barrier of hills into the

interior of Wilpena Pound, leading past the conserved remains of Hills'

Homestead. From there, a side route would take us up to the lower and upper Wangara Hill lookouts on the enclosing mountain rim of Wilpena Pound, offering

panoramic views into the entire geological feature (Map of Wilpena Pound). Having

now gained this greater understanding of Wilpena's topography, we thanked the

national park warden for her helpful advice, and went through to the small store

to stock up with food and water for the day. interior of Wilpena Pound, leading past the conserved remains of Hills'

Homestead. From there, a side route would take us up to the lower and upper Wangara Hill lookouts on the enclosing mountain rim of Wilpena Pound, offering

panoramic views into the entire geological feature (Map of Wilpena Pound). Having

now gained this greater understanding of Wilpena's topography, we thanked the

national park warden for her helpful advice, and went through to the small store

to stock up with food and water for the day.

Sliding Rock Gorge alongside Wilpena Creek: fully kitted up for a day's bushwalk in the hot

Australian outback sun, and armed with local maps and compass, we set off

through the groves of gum trees up into Sliding Rock Gorge alongside Wilpena

Creek (see above right) (Photo

33: Wilpena Creek footpath). The path was well-formed and

way-marked, and despite the number of cars at the parking area, was not unduly

crowded (see above right) (Photo

34: Sliding Rock Gorge bush-trail). The sunlight and dappled shade were magnificent (Photo

35: Wilpena dappled shade),

and the fascinating variety of gnarled old gum trees provided endless opportunity for

photography (Photo

36: Gnarled Gum trees) (see above right). The path followed the course of Wilpena Creek,

the drainage course for water gathering in the natural bowl of the Pound. The

creek was mainly dry at this time of year, but in places residual pools of

semi-stagnant water remained in the bed of the gorge (Photo

37: Semi-stagnant pools). We made frequent stops for photos amid the

groves of white-trunked Eucalyptus trees

(Photo

38: Eucalyptus groves).

The sky remained

clear and sun bright, (Photo

38: Eucalyptus groves).

The sky remained

clear and sun bright,

and the air was filled with the

calls and squawks of typical Australian bird-life, with good sightings of brightly colourful Rainbow

Lorikeets (see above left); we also saw, both in the gorge and on the higher Wangara slopes, specimens of Dusty Miller (Spyridium

phlebophyllum), a

characteristic plant of the Flinders rocky ridges (Photo

39: Dusty Miller - Spyridium phlebophyllum). We took our time, totally

revelling in these remarkably classic Aussie bush-land surroundings and

red-sandstone topography. and the air was filled with the

calls and squawks of typical Australian bird-life, with good sightings of brightly colourful Rainbow

Lorikeets (see above left); we also saw, both in the gorge and on the higher Wangara slopes, specimens of Dusty Miller (Spyridium

phlebophyllum), a

characteristic plant of the Flinders rocky ridges (Photo

39: Dusty Miller - Spyridium phlebophyllum). We took our time, totally

revelling in these remarkably classic Aussie bush-land surroundings and

red-sandstone topography.

Wilpena Gorge leading to remains of Hills'

Homestead: with all 3 of us relishing these 2 hours of glorious

photographic opportunities, we eventually emerged from the gorge at the entrance

to the Pound, to reach the site of Hills' Farmstead (Map of Wilpena Pound). Here we sat on a log in the

shade to eat our lunch. The restored shell of the Hills' family homestead stood

in the middle of the clearing, and information panels told the heart-rending story of their

struggles to clear the land in the Pound's basin for growing wheat and for

cattle grazing, and to overcome the problems of draught, disease and death. The

family had struggled on into the 20th century, until finally defeated

by the gorge road's flood destruction,

they gave up their heroic struggle to farm this impossible terrain and abandoned

their homestead. Their homestead ruins now stand as a memorial, and wording of the plaque said it all: if only the walls could

talk.

Panorama of Wilpena Pound from Wangara Lookout:

from the site of the homestead, we followed the steep, way-marked track which

gained height rapidly up rock steps (see above right), winding a way up the natural

slabs of sloping strata (see below left), around the red-sandstone outcrops (see

above left) (Photo

40: Wangara path), and rising steeply through scrub bushes

to emerge high above the tree-line

of

gums

(Photo

41: Wangara tree-line). This led after a

stiff climb to the lower lookout, giving initial

views across the inner depths

of the Pound. Further

climbing led across steep sandstone

slabs to emerge  onto the Upper Wangara Lookout, and from here a complete panorama opened up of the entire length and breadth of Wilpena Pound surrounded by its

enclosing circle of craggy sandstone hills (Photo

42: Scrub-covered Wilpena Pound); this superb vantage point gave the

perfect impression of the Pound's onto the Upper Wangara Lookout, and from here a complete panorama opened up of the entire length and breadth of Wilpena Pound surrounded by its

enclosing circle of craggy sandstone hills (Photo

42: Scrub-covered Wilpena Pound); this superb vantage point gave the

perfect impression of the Pound's

shape and structure. The original strata of

softer surface limestone within the Pound had over aeons been eroded away to

create this huge natural bowl, surrounded by the enclosing harder, more

resistant rim of sandstone (Photo

43: Wilpena panorama). The natural covering of bush, woodland and scrub across

the floor of the valley had reasserted itself over the last 100 years, after

having been partially cleared by the efforts of the Hill family to create wheat growing

areas and cattle grazing pastures (Photo

44: Scrub-covered Wilpena basin). But there were still clearer areas which we

interpreted as being more waterlogged where the trees were less inclined to grow. We

took our photos from this magnificent lookout position (see right) (Photo

45: Wilpena Pound), and began the descent of

the steep slabs, the sandstone giving good grip despite the gradient of the

slope (Photo

46: Descent from Wilpena rim). After a brief detour to a side rocky

outcrop for views to the NE, we continued the descent of the lower slopes back

down to the site of Hills' Homestead (see

below left); here we sat enjoying the shade among the trees for a

second lunch instalment of snack-bars and apple, and a refill of water bottles

from the rainwater storage tanks. shape and structure. The original strata of

softer surface limestone within the Pound had over aeons been eroded away to

create this huge natural bowl, surrounded by the enclosing harder, more

resistant rim of sandstone (Photo

43: Wilpena panorama). The natural covering of bush, woodland and scrub across

the floor of the valley had reasserted itself over the last 100 years, after

having been partially cleared by the efforts of the Hill family to create wheat growing

areas and cattle grazing pastures (Photo

44: Scrub-covered Wilpena basin). But there were still clearer areas which we

interpreted as being more waterlogged where the trees were less inclined to grow. We

took our photos from this magnificent lookout position (see right) (Photo

45: Wilpena Pound), and began the descent of

the steep slabs, the sandstone giving good grip despite the gradient of the

slope (Photo

46: Descent from Wilpena rim). After a brief detour to a side rocky

outcrop for views to the NE, we continued the descent of the lower slopes back

down to the site of Hills' Homestead (see

below left); here we sat enjoying the shade among the trees for a

second lunch instalment of snack-bars and apple, and a refill of water bottles

from the rainwater storage tanks.

With the sun still bright, we took a steady pace for the return walk back

down Wilpena Gorge. The gum trees took on a different appearance in the golden

light of afternoon, and yet more photos were taken. As we plodded down, we kept

a watchful eye for possible Koalas up in the tree branches, but unfortunately none were

seen. We did however pass a small flock of wild goats grazing

down in the creek

bed among the gum tree groves (see right), and completed the 8 kms circuit with the return to the car park by

the national park office. down in the creek

bed among the gum tree groves (see right), and completed the 8 kms circuit with the return to the car park by

the national park office.

Return to Hawker:

setting off at 3-30pm, we returned to the main road and turned south, just

getting a brief sighting of a pair of grey Kangaroos bounding across the road

100m ahead and disappearing into the pines. Wispy cloud had gathered, dimming

the bright sunlight, and we feared that this duller light would encourage more

Kangaroos across the road. We therefore took the return drive at a steadier

pace. There were several sightings of Emus and we paused to photograph a flock

grazing on a hillock amid the scrub (Photo

47: Grazing Emus). But none were close enough for detailed

photos. After pausing at one final lookout for more photos of the distant Elder

Range across the intervening bush-land

(Photo

48: Elder Range) (see below left) all lit by the now brighter afternoon sun, we reached Hawker at 4-15pm, and

scoured the poorly stocked general store for supper materials and a much-needed pack of

beer. The storekeeper should certainly have been happier than his manner suggested,

given the prices he was charging! Return to Hawker:

setting off at 3-30pm, we returned to the main road and turned south, just

getting a brief sighting of a pair of grey Kangaroos bounding across the road

100m ahead and disappearing into the pines. Wispy cloud had gathered, dimming

the bright sunlight, and we feared that this duller light would encourage more

Kangaroos across the road. We therefore took the return drive at a steadier

pace. There were several sightings of Emus and we paused to photograph a flock

grazing on a hillock amid the scrub (Photo

47: Grazing Emus). But none were close enough for detailed

photos. After pausing at one final lookout for more photos of the distant Elder

Range across the intervening bush-land

(Photo

48: Elder Range) (see below left) all lit by the now brighter afternoon sun, we reached Hawker at 4-15pm, and

scoured the poorly stocked general store for supper materials and a much-needed pack of

beer. The storekeeper should certainly have been happier than his manner suggested,

given the prices he was charging!

A second night in the peace of Wonoka sheep station:

rounding Wonoka Hill onto the main B83 road north, we turned

off onto the dirt track driveway to Wonoka Sheep Station (see below left)

through the seemingly barren

A second night in the peace of Wonoka sheep station:

rounding Wonoka Hill onto the main B83 road north, we turned

off onto the dirt track driveway to Wonoka Sheep Station (see below left)

through the seemingly barren bush-land grazing. We paused briefly to photograph

a dried up creek bed (see below right) (Photo

49: Dried up creek bed), and as we stood on the dry, red mud-banks,

Galah cockatoos swooped overhead and a Willie Wagtail with his fan-shaped tail flitted

around the dry creek bed. Back at Wonoka cottage, we

stood awhile chatting with Mr McInnis the owner about the local features. The state of the

local bush-land we could see around us was more or less natural, despite seeming

to us so barren; the only change

he could recall was the increase in growth of the low Acacia scrub encouraged by

sheep grazing. On the distance horizon, the Elder Range which we had

photographed earlier stood out clearly. The sun was just dipping below the

western hillside although it was only just gone 5-00pm and, while there was

still daylight, we prepared supper of sweet potato, chopped peppers and mushrooms to add

to the left-overs of last night's stir-fry, and barbecued sausages bought at Hawker. After

such a wearying but wonderfully satisfying day, we hungrily tucked into this

hearty supper.

bush-land grazing. We paused briefly to photograph

a dried up creek bed (see below right) (Photo

49: Dried up creek bed), and as we stood on the dry, red mud-banks,

Galah cockatoos swooped overhead and a Willie Wagtail with his fan-shaped tail flitted

around the dry creek bed. Back at Wonoka cottage, we

stood awhile chatting with Mr McInnis the owner about the local features. The state of the

local bush-land we could see around us was more or less natural, despite seeming

to us so barren; the only change

he could recall was the increase in growth of the low Acacia scrub encouraged by

sheep grazing. On the distance horizon, the Elder Range which we had

photographed earlier stood out clearly. The sun was just dipping below the

western hillside although it was only just gone 5-00pm and, while there was

still daylight, we prepared supper of sweet potato, chopped peppers and mushrooms to add

to the left-overs of last night's stir-fry, and barbecued sausages bought at Hawker. After

such a wearying but wonderfully satisfying day, we hungrily tucked into this

hearty supper.

Darkness fell quickly by 6-00pm and the full moon rose swiftly above the

eastern skyline giving the sky a bright light. We sat in the kitchen

after

supper, Lucy reading a book on the history of the Flinders from the cottage Darkness fell quickly by 6-00pm and the full moon rose swiftly above the

eastern skyline giving the sky a bright light. We sat in the kitchen

after

supper, Lucy reading a book on the history of the Flinders from the cottage bookshelf, Sheila researching tomorrow's return route, and Paul writing today's log.

Today had given such a wonderfully fulfilling set of new experiences and

learning, and from the Wangara high-point, we had been rewarded with such a

magnificent panorama of the complete circular bowl of Wilpena Pound and its

surrounding craggy enclosing sandstone hills. Tomorrow we should begin the

return journey down the eastern side of the Flinders Range.

bookshelf, Sheila researching tomorrow's return route, and Paul writing today's log.

Today had given such a wonderfully fulfilling set of new experiences and

learning, and from the Wangara high-point, we had been rewarded with such a

magnificent panorama of the complete circular bowl of Wilpena Pound and its

surrounding craggy enclosing sandstone hills. Tomorrow we should begin the

return journey down the eastern side of the Flinders Range.

Early morning at Wonoka sheep station: the alarm was set early

for 6‑15am to allow time for log completion, showers, loading the vehicle and

breakfast, and an early start at 8-00am. We were jerked into early consciousness

by the compelling need to rush outside to photograph a flaringly pink dawn sky

which cast a salmon glow over this wonderful Wonoka landscape

(Photo

50: Flaringly pink dawn sky) (see right). It was a startlingly bright

morning at Wonoka's peaceful setting, and again flocks of pink and

grey Galah cockatoos soared over the farmstead this morning

(Photo

51: Galah cockatoos). Before leaving, we

added suitably

appreciative comments in the visitors' book, and as we were

loading the car, Mr McInnis came over.

He told us that, what we had thought was

the smell of wild thyme, was simply the dewy grass drying in the morning

sunshine. He also described the creek we had stopped at last evening as more of

a storm water drainage; at times of heavy rain, the creek He told us that, what we had thought was

the smell of wild thyme, was simply the dewy grass drying in the morning

sunshine. He also described the creek we had stopped at last evening as more of

a storm water drainage; at times of heavy rain, the creek ran high and fast for

a couple of days, draining off the surface water, then drying up again to the

red sandy mud we had seen last evening. He also told us about Wonoka's water

gathering and storage arrangements: rain water was gathered into tanks for

drinking, and spring water pumped up from deep wells by the windmills we had

seen everywhere; this water was very brackish in taste from dissolved minerals

dating from aeons ago when SA was submerged. He gave us more details of his work

on the sheep station: his 2,000 sheep roamed freely over 20,000 hectares of

Wonoka's bush-land grazing; at shearing time they had to be rounded up by

driving around on his motorbike with his dogs. Although none of his sheep were

gathered in the shearing shed at present, he invited us over to see the recently

shorn Merino wool

(Photo

52: Sheep-shearing shed), and explained the routine of shearing and baling up the wool

for auctioning at Port Augusta market. Shearing at Wonoka was routinely carried

out once yearly in February, with contract shearing gangs coming in and paid by

the numbers of sheep shorn. Other stations sheared at different times of the

year to allow an evenly spread work schedule for the shearers. A sheep's wool

was shorn in one piece, and typically produced a 2 kg fleece. After sorting and

grading, (different grades of wool were sold at varying prices), the fleeces

were baled by machine into batches of ran high and fast for

a couple of days, draining off the surface water, then drying up again to the

red sandy mud we had seen last evening. He also told us about Wonoka's water

gathering and storage arrangements: rain water was gathered into tanks for

drinking, and spring water pumped up from deep wells by the windmills we had

seen everywhere; this water was very brackish in taste from dissolved minerals

dating from aeons ago when SA was submerged. He gave us more details of his work

on the sheep station: his 2,000 sheep roamed freely over 20,000 hectares of

Wonoka's bush-land grazing; at shearing time they had to be rounded up by

driving around on his motorbike with his dogs. Although none of his sheep were

gathered in the shearing shed at present, he invited us over to see the recently

shorn Merino wool

(Photo

52: Sheep-shearing shed), and explained the routine of shearing and baling up the wool

for auctioning at Port Augusta market. Shearing at Wonoka was routinely carried

out once yearly in February, with contract shearing gangs coming in and paid by

the numbers of sheep shorn. Other stations sheared at different times of the

year to allow an evenly spread work schedule for the shearers. A sheep's wool

was shorn in one piece, and typically produced a 2 kg fleece. After sorting and

grading, (different grades of wool were sold at varying prices), the fleeces

were baled by machine into batches of

104 kgs, for contractors to transport to

market. 104 kgs, for contractors to transport to

market.

We wished we had

time to stay longer at Wonoka and learn more about these fascinating new

experiences. He was an engaging and charmingly unassuming, taciturn man with a

delightful drawl; so interesting to listen to and to learn from. We had felt so

at home here at Wonoka; as Lucy so aptly put it, we should all leave part of

ourselves at Wonoka, and should take with us such rich memories, even from our

brief stay. We wished we had

time to stay longer at Wonoka and learn more about these fascinating new

experiences. He was an engaging and charmingly unassuming, taciturn man with a

delightful drawl; so interesting to listen to and to learn from. We had felt so

at home here at Wonoka; as Lucy so aptly put it, we should all leave part of

ourselves at Wonoka, and should take with us such rich memories, even from our

brief stay.

Kanyaka homestead ruins memorial site:

we said our farewells to Peter and Cheryl, and

drove back down the Wonoka driveway to the main road. Passing Hawker, we

continued south on a hot, sunny morning, and paused again to explore more

thoroughly the ruins of the 1850~60s sheep station of Kanyaka, founded

originally by Hugh Proby, which we had seen briefly on the outward drive. After Proby's death in 1852, his sheep station leases were taken over and enlarged by

partners Alexander Grant and John Philips, who settled here at Kanyaka and built

the homestead, wool shed and surrounding

dwellings during the 1850s. During

these years the Kanyaka sheep run had flourished, growing to over 360 square

miles in area, and despite the impact of drought, had at its peak shorn 60,000

head of sheep a year with up to 70 men and their families living at the

homestead. It also functioned as a staging point and post office on the road

north into the outback. But tragically the widespread and devastating droughts

of 1864~67 brought dwellings during the 1850s. During

these years the Kanyaka sheep run had flourished, growing to over 360 square

miles in area, and despite the impact of drought, had at its peak shorn 60,000

head of sheep a year with up to 70 men and their families living at the

homestead. It also functioned as a staging point and post office on the road

north into the outback. But tragically the widespread and devastating droughts

of 1864~67 brought an end to the great pastoral settlements; Kanyaka was

eventually abandoned by Philips in 1888, and the surviving sheep driven to the

Coorong area south of Adelaide. an end to the great pastoral settlements; Kanyaka was

eventually abandoned by Philips in 1888, and the surviving sheep driven to the

Coorong area south of Adelaide.

We turned off the main road down to Kanyaka's homestead

ruins (see above left), now preserved as a heritage site and memorial to those who had laboured,

suffered and striven to make a success of this pioneering settlement

(Photo

53: Kanyaka ruins) (see left). We walked

hesitantly across the bush-land to photograph the ruins, treading with

deliberate wariness in case of snakes lurking in the scrub. Down beyond the creek

lined with magnificent gum trees (see above right) (Photo

54: Gum tree lined dried creek), we walked around the

preserved ruins, amazed at how extensive the settlement had been at its height

(Photo

55: Impression of Kanyaka size), and stood sorrowfully to pay our respects at the settlement's

graveyard (Photo

56: Kanyaka graveyard) (see above right). Tragically the farmstead had not lasted long enough to fill the area

marked off as the settlement's

graveyard before the cruel natural hardships of

this wilderness had finally brought its downfall. Sadly we wondered what had

happened to the survivors of Kanyaka, despite all the efforts they had made to

farm these inhospitable outback lands and hardships they

had endured. graveyard before the cruel natural hardships of

this wilderness had finally brought its downfall. Sadly we wondered what had

happened to the survivors of Kanyaka, despite all the efforts they had made to

farm these inhospitable outback lands and hardships they

had endured.

Re-joining the main road, we set off again

southwards passing the point where we had joined this road from the outback

Willochra dirt track 2 days ago. Despite the speed at which traffic moved on

these dead straight main outback roads, every few kms signs warned of an

approaching floodway, the low-point dip where a creek water-course crossed the

road at times of rainfall. From a distance, the dry creek bed was visible lined

with gum trees. At the centre-point of each floodway, a

water depth post showed that, in times of heavy rain, a torrent of up to 2m

depth could surge across the road at this point (see left). We heard of

motorists being drowned through careless crossing at such floodways. A number of elaborate caravans pulled by 4WD

vehicles passed by heading north, perhaps reflecting the approaching Easter

holidays. The morning continued bright as we made good progress southwards, back

into Quorn to pass the railway station and Austral pub which we had left

seemingly weeks ago. Re-joining the main road, we set off again

southwards passing the point where we had joined this road from the outback

Willochra dirt track 2 days ago. Despite the speed at which traffic moved on

these dead straight main outback roads, every few kms signs warned of an

approaching floodway, the low-point dip where a creek water-course crossed the

road at times of rainfall. From a distance, the dry creek bed was visible lined

with gum trees. At the centre-point of each floodway, a

water depth post showed that, in times of heavy rain, a torrent of up to 2m

depth could surge across the road at this point (see left). We heard of

motorists being drowned through careless crossing at such floodways. A number of elaborate caravans pulled by 4WD

vehicles passed by heading north, perhaps reflecting the approaching Easter

holidays. The morning continued bright as we made good progress southwards, back

into Quorn to pass the railway station and Austral pub which we had left

seemingly weeks ago.

The one-horse outback town of Wilmington: turning off by the

Austral pub, we started on the road across the broad, empty Willochra Plain,

the northern arid outback-lands now giving way to prairies of rough pastureland

or stubble from harvested crops. The lonely road extended away southwards,

totally straight and empty. By 11-00am, we reached Wilmington where we hoped to

buy food for today's lunch. A superficially attractive, one-street town where we

filled up with fuel at the one garage, it in fact proved to be a totally

one-horse town, and being Tuesday, the one horse was on its day off: the local

café was closed, and the poorly stocked general stores was unable or unwilling

to provide further provisions. Unsupplied, with other than pasties and sausage

rolls, we pressed on, and soon after, turned off up to the northern end of Mount

Remarkable National Park. The one-horse outback town of Wilmington: turning off by the

Austral pub, we started on the road across the broad, empty Willochra Plain,

the northern arid outback-lands now giving way to prairies of rough pastureland

or stubble from harvested crops. The lonely road extended away southwards,