|

** AUSTRALIA 2011 - PERTH ** |

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Onward flight from Adelaide to Perth: we were up early in order for Lucy to drive us to the airport before she went to work. Traffic was light and we reached the airport by 8-15am, unloading our heavy packs and bags onto a trolley. We gave Lucy farewell hugs and she left for work. Inside the terminal, we checked-in and handed in our packs. Relieved of their weight, we went through for a coffee before settling in to the seats by Gate 22 for our morning's wait.

The Boeing 737 aircraft came in and unloaded

(Photo 1 - Qantas 737 at Adelaide)

(see below left), but our expected 11-10 boarding was delayed. We

eventually were cleared to board some 20 minutes after our scheduled take-off

time at 11-50. Seeing the vast size and quantities of hand-luggage hauled aboard

A reasonable lunch was served on the flight along with cans of James Squire's beer, followed by an ice-cream. Having taken off over the SA coast at Glenelg, the flight route followed the Australian coastline above the Southern Ocean, the cloud layer progressively breaking as we advanced westwards towards Perth. At some point, the flight path turned in across land, and for the final 30 minutes of the flight we flew across the arid-looking plains and dried river beds of the Western Australian desert-lands (see maps of Perth and Western Australia above right). Arrival at Perth: the plane landed at Perth Domestic Airport virtually on time around 1-30 (Perth time was 1½ hours behind of Adelaide), and we collected our packs from the carrousel. The first black mark against Perth was that $4 was charged for an airport baggage trolley; that was the first time we had ever encountered this during our Far-Eastern travels. The second negative was the paucity of public transport from airport to city, and we waited almost 30 minutes for the #37 bus. We bundled aboard, and the bus made another 30 minutes circular tour of the city's outer suburbs before crossing the wide Swan River and dropping us close to the Exclusive Back-packers Hostel in Adelaide Terrace, our home for the next 3 nights. History of Perth: Perth has a slightly older history than Adelaide. The colony was founded in 1829, largely because the British feared the French would establish a colony in Western Australia. In 1827 Captain James Stirling had sailed into the Swan River in his ship HMS Success, believing the area would be ideal for a settlement. He persuaded the British government to found a colony there, independent of the penal colony in New South Wales. Perth was to be named after Perthshire in Scotland, the birthplace of Sir George Murray, the then British Secretary of State for the Colonies. The colony was not to be a convict penal settlement; instead the government would sell plots of land cheaply to private citizens (regardless of any claims the Indigenous Australians who lived there might have), and the first ship to arrive in the Swan River estuary was HMS Challenger, a 28 gun frigate captained by Charles Fremantle. On 2 May 1829, he claimed the whole of Australia outside of New South Wales for Britain in the name of King George IV. Stirling was appointed Governor and arrived in June 1829 with the first settlers, to found Perth as part of the new free Swan River Colony, with Fremantle as its port at the mouth of the Swan River. The district of Guildford had the best quality soil and was settled in the first year of the colony. But the impact of the early colony's expansion into traditionally aboriginal lands had the usual destructive effect on the indigenous population who had lived in the south-western region of Western Australia for more than 35,000 years. The local Noongar peoples were displaced and dispossessed of their traditional lands, and subjected to harsh and unsympathetic colonial rule by the intruding white settlers. Captain Stirling had been impressed by the beauty of the Swan River and the apparently fertile land around it. Much of the land however turned out to be too sandy and unsuitable for agriculture, and the first reports of the colony were not as glowing as Stirling had been led to expect. As a result, Perth grew slowly during the first two decades after its foundation; although it gained city status in 1856, the free colony experienced a shortage of manpower and finance, and communications difficulties in this remote location. After this early period of meagre growth, the British government therefore agreed to send some 10,000 convicts to Western Australia between 1850 and 1868 to support the colony's development. Large amounts of the city's infrastructure were built by convict labour, shaping the character of the city, but Perth continued its slow growth as a now part-penal settlement. In 1881 Perth was connected to Fremantle by railway, and in 1877 a telegraph line from Adelaide to Perth was completed, vastly improving intra-continental communication. But Perth's underlying identity as a remote frontier-town and back-water remained unchanged. The discovery of gold around Kimberly and Kalgoorlie in the 1890s produced a huge impact on the development of Perth, with an increase in population and wealth. The physical nature of the city changed dramatically with economic prosperity: Perth Mint was built in 1899 and the University of Western Australia was founded in 1911; at the end of the 19th century Perth gained an electricity supply, and in 1899 electric trams began running in the streets. There was a marked increase of population as a result of gold rush immigration: in one decade the population of the city tripled, from 8,447 in 1891 to 27,553 in 1901. By the beginning of the twentieth century, Perth was totally transformed. Its streets were lined with elaborately styled multi-storey buildings, and the population had spilled over into new suburbs that encircled the city. On the promise of the trans-continental rail-line across the Nullarbor Desert from Port Augusta to Kalgoorlie and Perth, Western Australia joined the newly formed federated Commonwealth of Australia in 1901, with Perth as its State capital. Into the first half of the 20th century, the population of Perth enlarged further and changed in character and culture with post-WW2 immigration. The expansion of large-scale mining and the mineral exploitation boom of the 1970~80s brought further expansion to Perth, as international mining and financial conglomerates built skyscraper office blocks which transformed Perth's city appearance dramatically. In the 1990s however the city's clean-cut, nouveau-riche image was tarnished by a series of major financial and political scandals. And here we now stood amid the tower-blocks of Perth's city centre.

An initial afternoon getting the lie of the land in Perth: we walked along Hay Street past a few restaurants and cafés as potential supper venues (click here for map of Perth), and identified the location of the Perth Mint which processed the products of gold mining bringing much wealth to the city. Along at the centre, large scale roadworks brought chaos to the streets, as we caught our first Red CAT bus around past the railway station. We managed to find the TIC amid the road works, and there with the helpful advice the staff we pieced together our plans for the two days in Perth; we were also able to book tickets for the river-cruise down the Swan River to the coast at Fremantle for Friday. Having left Adelaide this morning in cool weather and pouring rain, we now faced hot and very glaring sun in Perth with temperatures in the mid-20s; what would it be like in the insufferable temperatures of mid-summer! Having also become accustomed to the colonial grace and charm of Adelaide's city architecture, Perth came as something of a culture shock. With its ultra-modern city-scape and high-rise office blocks, it seemed an utterly soulless and unattractive city, an impression which did not improve as we walked around the pedestrianised central area with its brash shops and hustling crowds. We walked through the shopping arcades, along past pretentious shops selling tourist ephemera, and enquired further at the TIC about possible visits to the WACA (Western Australian Cricket Association) Oval cricket ground. We then discovered the city transport office for CAT-plans of the free city centre circular buses, and details of other public transport, or rather lack of it, out to the more distant and separate International Airport for our departure from Perth on Saturday. The hot, bright sun was now setting fast behind the city skyscrapers; it was 5-30pm and to round off our highly successful afternoon of fact finding, we rode the complete city centre-wide circuit of the free of charge Red CAT bus through the slowly moving evening traffic. By the time we reached the eastern end of the circuit, passing the WACA at 6-15, it was totally dark and we could see nothing of the cricket ground. We got off the bus by the Perth Mint in Hay Street for an early evening beer and possible pub supper at the Salisbury pub we had seen earlier. The local Perth beer from the Swan Brewery was an utterly tasteless lager, far from the standard we were accustomed to in Adelaide; we therefore reverted to James Squire's Amber previously drunk in Sydney. But the price of basic pub food in Perth was horrendous: mid~upper $20s for even straightforward menu options; this was our first experience of the notoriously high cost of living in Perth, far worse even than Sydney. Instead we walked around to an Indian restaurant seen earlier near the hostel and enjoyed a very tasty curry and very polite service. But again horrific prices; at this rate we should be broke before Saturday! We bought some basic foodstuffs for breakfast at a supermarket opposite, and returned to the hostel to settle in for the night. Exclusive Backpackers Hospital, our accommodation in Perth: the Exclusive Backpackers Hostel proved to be a less agreeable experience than first impressions yesterday had suggested: while the room was satisfactory, there was a lengthy walk around corridors to the communal loos and showers; traffic noise from the open window was a nuisance, and the kitchen was poorly equipped. But even worse was the disturbing noise of raised voices from a neighbouring room which disrupted our night's sleep. This morning, the young oriental offenders were challenged and claimed to have been praying from 2-00~4-00am; then please do so more quietly without waking others, Paul demanded with authoritative assertiveness. Fortunately they checked out this morning. Our first day in Perth and visit to Perth Royal Mint: we set off at 9-30am for our first day in Perth, on another warm, sunny morning but today at least with a refreshing breeze. Along Hay Street we reached Perth's Royal Mint with its colonial-style building fronted by elegant lawns. Here we were greeted by a wretchedly surly madame with unsmiling, Gorgon-like lack of manners. She did however accept Paul's bus pass as evidence meriting a seniors' reduction, albeit minimal, on the $15 entry charge, but then offensively refused the same for Sheila who did not have her card. Her surly manner was totally impervious to Paul's irony-laden response! The Perth Royal Mint was founded in 1899 as a colonial branch of Britain's London Mint, to refine gold discovered in Western Australia's goldfields, and to mint sovereigns and half-sovereigns for use throughout the Empire. During the 1890s, those seeking to make their fortune had flocked to the eastern outback of Western Australia, where gold had been discovered by prospectors represented by the statue that stood in the gardens of the Perth Mint. Prospectors made their way on foot across the 600 kms of desert in search of their fortune. Gold mining had continued ever since, increasing Western Australia's economic prosperity. During the 20th century, even after the State's incorporation into the Australian Federation, the Perth Mint continued to operate under British control, until ownership was passed to the Western Australian government in 1970, with the Mint producing the bulk of Australia's currency. Today it produces commemorative medals and coins, and acts as a bullion market. It still refines almost all of Australia's entire gold production. We waited for the official tour at 11-00am, and the guide explained the history of the Western Australia 1890s gold-rush, and the establishment and development of the Perth Royal Mint to refine the output of the Western Australia gold fields. A mock-up showed the primitive conditions of a prospecting camp. The tour of the Perth Mint began with a display of pouring molten gold from the furnace to produce a 6 kgs bar of solid gold. These daily demonstrations of gold pouring had been taking place for some 30 years, using the same 6 kgs quantity of 99.5% pure gold. Gold melts at 1,064°C, and was heated in the furnace to 1,300°C. The demonstrator introduced the process in the former refining room now converted for public displays. Wearing protective clothing, visor-helmet and arms-length gloves, he lifted the red-hot glowing clay crucible of molten gold from the furnace with long-handled tongues, and poured the liquid gold into the cast-iron mould. The gold began to cool immediately, and within moments had solidified into an ingot. This was then plunged into a water bath to cool, and he lifted the bar out for us to examine; it was worth $200,000. After the display, we walked around the museum displays of samples of unrefined gold nuggets, which included the world's second largest existing natural gold nugget specimen ever found, the Normandy Nugget, discovered in a dry creek-bed near Kalgoorlie in 1995; it weighed 819 troy ounces (25,473.75 gms), and measured approximately 11 by 8 inches. It currently ranked as the 26th largest gold nugget ever unearthed, but most of the largest nuggets have been melted down for their gold content. It was owned by the Newmont Mining Corporation, and was currently on long-term loan for display at the Perth Mint. The display also gave opportunity for visitors to place a hand into a cabinet and attempt to lift a solid bar of gold weighing 12 kgs. Another curiosity was a set of step-on scales where your body weight was translated literally into its value in gold: Sheila weighed in at $2.5 million, and Paul at almost $3 million! We asked the guide about the enormous gold mining quarry-pit we had flown over on the flight to Perth. This, we learned, was the Kalgoorlie Super Pit, a vast open-cast gold mine 3.5 kms long, 1.5 kms wide and over 600m deep, now operated by the Kalgoorlie Consolidated Gold Mines mining conglomerate; see the Super Pit web site about mineral processing to extract gold. While inevitably contrived, the Perth Mint visit had been a novel experience, symbolising the source of wealth on which the entire Western Australia modern economy had been built. A hugely rewarding visit to Perth Museum: from Hay Street we caught the Red CAT bus along to the centre, and changed to the Blue CAT bus up to the Northbridge district beyond the railway station to find the Perth Museum which houses Western Australia’s scientific and cultural collections. The museum layout was something of a maze spread over three floors, but the receptionist suggested a route around to see the main permanent displays. Leaving behind the crowds, we went up to the first floor to the displays which illustrated the history of Western Australia from pre-historical times, through the period of colonial settlement, to the expansion of farming and pastoralism in remote areas of Western Australia during the 20th century, and modern large-scale mining exploitation during contemporary times. The section on 20th century farming and pastoralism expansion emphasised the hardships of life in remote homesteads and sheep stations, and the destructive impact of the expansion of grazing land and timber exploitation on natural landscape and trees. One particular display showed the devastating effect of the introduction of rabbits into Western Australia, and resultant measures to control them as vermin, including installation of 1000s miles of rabbit-proof fencing along the remote borders of the State. Subsequent displays illustrated the discovery of gold and later large-scale mining and mineral exploitation, and reliance of the Western Australian economy on this. Impact of European colonisation and Aboriginal rights: but what interested us the most were the presentations illustrating the traditional life-style of the Aboriginal Noongar peoples of SW Australia, and the destructive impact of the early~mid-19th century period of European colonisation, or invasion as it was styled for political correctness. The displays dealt not only with the hardships of the early settlers, but also the effect of expanding white settlement on the Aboriginal occupants of the lands. Indigenous peoples, who had lived in Australia for at least 65,000 years before the arrival of British settlers in 1788, were dispossessed of their land by Britain which claimed Australia as its own on the basis of the spurious and now discredited legal doctrine of Terra Nullius (land belonging to no one). The settlement of Australia was the exception to British imperial colonisation practice in other parts of the world, in that no treaty was drawn up setting out the terms of agreement between settlers and native land owners, as was the case in North America and New Zealand. British colonisation and subsequent Australian land laws were established on the basis that Australia was Terra Nullius, justifying acquisition by British occupation without treaty or payment, effectively denying Indigenous people's prior occupation of and connection to the land. Initially, Indigenous Australians were in most states deprived of the rights of full citizenship of the new nation on grounds of their race, and subsequent restrictive immigration laws were introduced giving preference to white European immigrants to Australia. Discriminatory laws against Indigenous people and multi-ethnic immigration were only dismantled in the early decades of the post-war period. A Referendum in 1967 regarding Aboriginal rights was carried with over 90% approval by the electorate. But only from the 1970s have legal reforms, won by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, re-established Aboriginal Land Rights under Australian law, 200 years after the arrival of the First Fleet at Botany Bay. Noted High Court cases like Mabo v Queensland (1988 and 1992) upheld Indigenous peoples' claims to land ownership, rejecting the legal doctrine of Terra Nullius, and re-asserted that indigenous land rights continued to exist in Australia. In the early 21st century, Indigenous Australians accounted for around 3.3% of the population, owning outright around 20% of all land, largely in the sparsely inhabited central Australian desert rather than the resource rich coastlines. Aboriginal health however and social living standards indicators remain lower than other ethnic groups within Australia, and are the subject of continued political debate. Perth Museum displays about the Stolen Generations issue: the most gruellingly moving part of this display in the Perth Museum however was the detail given to another notorious aspect of the White Australia Policy during the early~mid 20th century, which had such a devastating impact on the Indigenous peoples of Western Australia and the other states of the Australian Commonwealth; this was the highly controversial issue of the so-called Stolen Generations. We had heard of this, but knew nothing about it. Under this policy, and on a spurious assumption that the Aboriginal peoples were dying out, children of aboriginal descent and of mixed race parentage were forcibly removed from their families by Australian federal and state government agencies and church missions. They were handed over to charitable and religious institutions or white foster homes, with the intention of eradicating aboriginal culture, and the policy was enforced by police and government inspectors. The underlying premise was if that such children were removed from their natural parents and excluded from their communities and homeland, they could be re-educated from their aboriginal culture, trained to work in white society, and over generations would marry and be assimilated into white society. Children were removed from their mothers and taken into care, purportedly to protect them from neglect and abuse, but ignoring all the horrors, exploitation and abuse that this entailed. Later reports showed many suffered sexual exploitation while in an institution, or living with a foster or adoptive family. Official government estimates were that between one in ten and one in three Indigenous Australian children were forcibly taken from their families and communities between 1910 and 1970; the policy continued in some regions as late as the 1980s. By around the age of 18, the children were released from government control. Widespread awareness of the Stolen Generations issue, and the practices that created it, grew in the late 1980s through the efforts of Aboriginal and white activists, artists, and musicians. The Mabo v Queensland cases attracted great media and public attention to all the issues related to the government treatment of Aboriginal Peoples in Australia. Australians became more aware of such policies, most notably the Stolen Generations outrage, and the large-scale negative impact of past government policies that had resulted in the removal of thousands of mixed-race and Aboriginal children from their families to be reared in a variety of conditions in missions, orphanages, reserves, and white foster homes. The Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission's National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families, set up by the Keating government, began work in May 1995. During the following 17 months, the Inquiry visited every State and Territory in Australia, heard testimony from 535 Aboriginal Australians, and received submissions of evidence from more than 600 more. In April 1997, the Commission released its official report Bringing Them Home. But between the commissioning of the National Inquiry and the release of the final report in 1997, the Liberal government of John Howard had replaced the Paul Keating Labour government. At the Australian Reconciliation Convention in May 1997, Howard was quoted as saying: "Australians of this generation should not be required to accept guilt and blame for past actions and policies". Following publication of the report, the State Parliaments of the Northern Territory, Victoria, South Australia, and New South Wales passed formal apologies to the Aboriginal people affected. On 26 May 1998, the first National Sorry Day was held; reconciliation events were held nationally, and attended by a total of more than one million people. As public pressure continued to increase on the federal government, John Howard introduced to the Federal Parliament a Motion of Reconciliation, expressing "deep and sincere regret over the removal of Aboriginal children from their parents", which was passed in August 1999. Howard said that the Stolen Generation represented "the most blemished chapter in the history of this country", but resolutely refused formally to apologise. Activists took the issue of the Stolen Generations to the United Nations Commission on Human Rights. At its hearing on this subject in July 2000, the UN Commission strongly criticised the Howard government for failing to support a national apology or making monetary compensation to those "forcibly and unjustifiably separated from their families, on the grounds that such practices were sanctioned by law at the time". It took however almost another decade of intense focus on the impact of the Stolen Generations policy until on 13 February 2008, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd presented an apology to Indigenous Australians as a motion in the Federal parliament. The text of the apology made no mention however to compensation to Aboriginal people generally or to members of the Stolen Generations specifically. The Opposition Leader's half-hearted speech of support for the apology triggered nationwide protests: 1000s of people gathered in public spaces around Australia to hear the apology turned their backs on the broadcast screens. In Perth, people booed and jeered until the screen was switched off. In Parliament, elements of the audience began a slow clap, with some finally turning their backs. The apology was unanimously adopted by both houses of the Federal Parliament, but to date the legal circumstances regarding the Stolen Generations policy remain unclear; no compensation claims have yet been settled. We were more than deeply moved by what we had learned from this frank and horrific presentation in the Perth Museum about the dreadful, inhuman impact of the Stolen Generations policy, what has been described by some as a further example of genocide.

Perth Museum displays on Australian Marsupials and Monotremes: we concluded our museum visit in the mammals gallery, where the information panels gave further details about uniquely Australian Marsupials and Monotremes, which we found particularly fascinating. There are three groups of mammals alive today: the egg-laying Monotremes (Echidnas and Platypuses), the Marsupials, and the Placental Mammals. The major physiological difference between Marsupial and Placental Mammals is how they reproduce. Placental mammals develop a placenta in the uterus and give birth to comparatively well-developed young. In contrast, Marsupials give birth soon after conception to small and relatively underdeveloped young, which develop in pouches in the mother's abdomen. Some Marsupial newborn are so tiny and at such an early stage of development that they breathe through their skin because their lungs have not yet properly formed. The Marsupial newborn (joey) must find its own way into its mother's pouch and latch on to a nipple to survive. Different groups of Marsupials manage this in different ways, but the most impressive is the long uphill climb of a small, sticky Kangaroo newborn: about the size of a jelly-baby, the tiny joey has to crawl up its mother's hairy abdomen using only its forelimbs (the hind limbs are not yet developed) to reach the safety of the pouch. Marsupials and Placentals are sister groups, more closely related to each other than to Monotremes. Marsupials are much less diverse than Placental mammals in terms of numbers of different groups, range of lifestyles, body shapes and habitat. Marsupials share a common line of descent with Placental mammals, having a common ancestor around 200 million years ago in the early Cretaceous period. Fossil Marsupials have been found from the American continent, Australasia, Western Europe, and North Africa. 75% however of living Marsupials are found in Australasia with only a few smaller examples surviving mainly in South America (eg Opossums). DNA evidence suggests that Marsupials originated in Asia, and dispersed into the southern hemisphere mega-continent of Gondwana around the beginning of the Palaeocene epoch (65 million years ago). The earliest fossil records suggest that extant Australian Marsupial orders evolved from ancestors which migrated from South America via Antarctica as a stepping stone to Australasia sometime during the Late Cretaceous or early Palaeogene, before the Australian continent finally separated from Antarctica after the opening of Drake Passage between South America and Antarctica around 43~35 million years ago. The Marsupial orders diverged prior to the late Oligocene Period (23 million years ago), to produce ancestors of the current Diprotodontia, an order of around 155 Marsupial species, including Kangaroos, Wallabies, Possums, Koala, and Wombats. Extinct examples include the rhinoceros-sized Diprotodon, the largest of the Australian Megafauna and ancestor of modern Wombats, the Procoptodon giant Kangaroo, and the Thylacine (so-called Marsupial Lion), the largest of the carnivorous Marsupials and forerunner of the Tasmanian Tiger now also extinct.

Like Marsupials and Placental Mammals, the Monotremes are warm-blooded. Although they were once

more widespread, including some extinct species in South America, the only

extant surviving species of Monotremes, the Platypus and Echidnas, are both

indigenous to Australia and New Guinea. The key anatomical

The divergence of Monotreme ancestry from Marsupial and Placental Mammal lineage happened around 200 million years ago, prior to the divergence between Marsupials and Placental Mammals around 180 million years ago. Click here for an Evolutionary Chart which shows the evolutionary relationships between birds, reptiles and the three Mammalian groups (including Monotremes), and the timescale in millions of years ago between their diversification. The common ancestor of all three classes of Mammals, including the Monotremes, were the Synapsid proto-mammals, sometimes loosely called mammal-like reptiles. The Synapsids were all rather lizard-like in appearance, egg-laying, with sprawling gait and some with horny external plates. They diversified over 300 million years ago from the Sauropsids which gave rise over evolutionary time to the dinosaurs and later to modern birds and reptiles. Unlike other modern Mammals, the Monotremes retain many of the reptile-like features inherited from their Synapsid ancestors.

When the Platypus was first encountered by Europeans in the late 18th century, its unusual appearance and characteristics caused naturalists to believe that it was a taxidermied fake, made up of several animal parts stitched together. Until the early 20th century, Platypus were slaughtered for their fur almost to the point of extinction; despite now being strictly protected, they are still vulnerable to pollution, habitat destruction, climate change, and predation, and have disappeared totally from the lower Murray-Darling basin.

Public transport to King's Park and Perth Botanic Gardens: it was by now 2-30 and we had to find the quickest public transport route up to Kings Park. From the James Street bus stop (click here for map of Perth), we caught the Blue CAT bus two stops down to William Street, and the #37 bus from St George's Terrace up the steep hill of Malcolm Street to the terminus at Kings Park. Here we found the Visitor Information Centre, and the enthusiastically helpful volunteers gave us details of the Perth Botanic Gardens with its high-level walk-way which led, partly at tree-top level, through a conservation area of Western Australia trees and vegetation. We also asked for advice on the best place for afternoon views over the city and Swan River, and were recommended to walk over to the Western Australia War Memorial where the Perth ANZAC Day Dawn Service is held.

More immediately below us, the scrub-covered cliff was conserved as part of the WW1 memorial, said to resemble

the cliff at Anzac Beach where the ANZAC forces had tried to gain a foothold on

the exposed Gallipoli headland in the face of irresistible machine gun fire from

the Turks dug into the cliffs above. Having taken our

photos looking across the Swan River and city panorama, we paid our respects at

the Western Australia War Memorial (see left) (Photo

9 - WA War Memorial). The names inscribed on the memorial's walls

commemorated the 7,000 men of Western Australia who had fallen victim during

WW1. Behind the memorial, the Flame of Remembrance burned in the memorial

gardens. The plaque

The pathway led through many varieties of gum trees and look-outs overlooking the river to

the Federation Walkway. Where the slope of the ground fell away down into a

valley, the high-level aerial walkway continued, now at tree-top level through

the Eucalyptus canopy, and at this height looking down onto the

treetops below, we had good sightings of more Crimson Rosellas flitting among

the branches. As we approached the walk-way's highest point, a spectacular

arched bridge with glass walls at a height of 16m gave uninterrupted views to

the forest floor and a panorama of the Swan and Canning Rivers. The whole

walkway is 620m in length, with the aerial section being 222m including the 52m

bridge. Reaching the far end of the high-level walkway, we turned back along the

lower-level path alongside a stream. A family we had been following told us

there were Kookaburras flying among the trees; we failed to see these, but

The pathway rose up the slope back through the gardens of Banksia (named after Sir Joseph Banks,

the botanist on Captain Cook's Endeavour expedition who first identified

them in 1770) which grow as evergreen trees or woody shrubs. A number of

varieties of Banksia shrubs grew in the Botanic Gardens, displaying their

curiously shaped characteristic flower spikes, made up of a woody core covered

with hundreds of florets, ranging in

colour from shades of yellow, orange, pink and red.

Magnificent relics from the super-continent of Gondwana, Banksias are a uniquely

endemic Australian plant; of the 76 species recorded nationally, 62 are native

to Western Australia, many of which were shown here in the Perth Botanic

Gardens' Banksia Garden collection. Despite most of the specimens now being in

shade by this time of the afternoon, we were able to photograph Banksia media

(Southern Plains Banksia) (Photo

12 - Southern Plains Banksia) which grows along the southern coast of WA;

Banksia ashbyi (Ashby's Banksia), growing

in the sandy soil of WA's western coastal heathland (Photo

13 - Ashby's Banksia) (see left); Banksia menziesii (Firewood

Banksia) (Photo

14 - Firewood Banksia), a native also of WA's western coast;

Banksia baueri (Possum or Woolly Banksia) (see below right) (Photo

15 - Possum or Woolly Banksia), a dense shrub found on WA's southern coast. Being heavy producers of nectar, Banksias

are a vital part of the food chain in the Australian bush; they are an important

food source for all sorts of

Nearby

Returning uphill along a shady avenue of Eucalyptus trees, we photographed

several varieties of Eucalyptus

with their characteristic sequence of bud, flower, and fruit.

There are more than 700 species of the Eucalyptus genus, and over

the seven weeks of our time in Australia, we had seen so many different varieties of

Eucalyptus, difficult as they all were to identify. The Eucalyptus flower is its

most distinctive feature with numerous fluffy stamens, white or coloured,

enclosed in a cap formed from

fused petals or sepals. As the stamens expand, the cap is forced off splitting

away from the cup-like flower base. The fruit is a woody capsule, referred to

colloquially as a gum-nut, cone-shaped with a valve at the end

An oriental supper in Perth:

back up at the Visitor Centre, we caught the #37 bus back down to St George's

Terrace in the evening rush-hour, and transferred to the Blue CAT bus back up to

Northbridge for an early evening beer at the Brass Monkey, an attractive

traditional

corner pub along James Street near the Perth Museum where we had

been

The Blue CAT bus took us back across the railway bridge to pick up the Red CAT along to

Murray Street. By now the evening was dark, preventing us from seeing details of

Perth Cathedral's Victorian Gothic flying buttresses, so artificial-looking they

almost seemed as if made of papier-mâché! Along Hay Street, we ventured into an

Asian barbecue-restaurant for supper. Here despite our weariness after a long

day, another novel experience awaited us: a cook-it-yourself supper. The

young lady, of uncertain Asiatic origin, sat us at a table with its built-in

barbecue

The ferry pulled away from the pier, opening up increasingly impressive views

across the Perth city sky-scape (see left) (Photo

21 - Ferry piers for Swan River cruises).

The morning sun gave wonderful lighting conditions for back-lit shots of the Perth cityscape tower-blocks as we

headed down-river (see right) (Photo

22 - Perth city sky-scape), and more personal souvenir photos of the river cruise (Photo

23 - Swan River cruise). But it was views from the river across to the

city that irresistibly held our attention (Photo

24 - Perth from Swan River) (see below left). The ferry passed below the  were moored here being loaded with their cargoes by dock-side gantries. Typical

turn-around times at the container terminal for unloading and re-loading were

just 36 hours. The ferry docked on the inner, town side

of the wide estuary which formed Fremantle docks (Photo

28 - Fremantle docks); ahead we could see the mouth of

the Swan River with the Indian Ocean beyond. At this stage we had lost all sense

of orientation of where exactly we had come ashore. Once on land however we took

time to get our bearings amid the towering dockland cranes and former cargo sheds (Photo

29 - Dockland crane and cargo sheds) (see below left), one of which

Shed E was now used as a covered market.

were moored here being loaded with their cargoes by dock-side gantries. Typical

turn-around times at the container terminal for unloading and re-loading were

just 36 hours. The ferry docked on the inner, town side

of the wide estuary which formed Fremantle docks (Photo

28 - Fremantle docks); ahead we could see the mouth of

the Swan River with the Indian Ocean beyond. At this stage we had lost all sense

of orientation of where exactly we had come ashore. Once on land however we took

time to get our bearings amid the towering dockland cranes and former cargo sheds (Photo

29 - Dockland crane and cargo sheds) (see below left), one of which

Shed E was now used as a covered market.

Fremantle Harbour South Mole and distant views of Rottnest Island: across a large car park, we could make out Fremantle railway station, which enabled us to

pinpoint our position (click

here for map of Fremantle). Despite having acquired reasonably legible

town plans, it took us a while to extricate ourselves from the car park and to

identify surrounding buildings. Eventually we worked our way around to the South

Mole (Photo

30 - South Mole of Fremantle Harbour) (see below right) which extended to enclose the entrance

to Fremantle Harbour and the outflow

of the Swan River into the Indian Ocean. Although now artificially

extended to protect

Colonial-era buildings of Fremantle Harbour area:

out by the lighthouse at the outer end of the mole, we took our photos looking across the

Indian Ocean (Photo

34 - Indian Ocean), and returned past the harbour entrance and Maritime Museum to

climb up to the restored Round House on the prominent headland overlooking the

river mouth. This was the first public building of the Swan River Colony. Built

in 1830 from local white limestone, it was used as a jail to house convicts who

were transported to Western Australia from 1850~68 to provide an enhanced labour

workforce for the fledging colony. After the construction of the larger

Fremantle jail, the Roundhouse was used to imprison minor offenders. From 1900

a time-ball was dropped and cannon fired at 1-00pm each day to give Fremantle

residents an exact time

Freemantle Bathers' Beach:

Fremantle's Bathers' Beach set just below the headland (see below left) (Photo

36 - Fremantle Bathers' beach) looked very attractive today with its

white sands. It was however in the early days of the colony the site of a

whaling station from where the Fremantle Whaling Company operated in the bay. A

tunnel and cutting was chopped through the limestone headland in 1838 to transport heavy equipment and the processed products of

whaling directly to and from the town and the jetty (Photo

37 - Whaling cutting). We walked around

by the beach and through the former whaling tunnel, and followed the dockland

railway around to the small fishing harbour. Here we found an attractive area of

fish restaurants which we had identified from recommendations in Rough Guide as

a possible lunch venue; although prices would inevitably be

Lunch at Fremantle Harbour: as we walked around towards the fishing

harbour (click

here for map of Fremantle), a train of container-wagons chugged around from the docks,

as if emphasising that although attractive Fremantle was still essentially a working

port. A few boats were moored in the fishing harbour (Photo

38 - Fishing boats) (see below right), and gulls perched on mooring posts (Photo

39 - Perching gulls) (see below left). We compared the prices and menus of three fish restaurants and decided that the original

one, Cicerello's was the most suitable for our lunch, with its outdoor seating

terraced right out

Fremantle's Victorian Market Hall:

utterly replete from our very memorable lunch at Fremantle fishing harbour, we walked across the parkland of the Esplanade

Reserve, and up Essex Street into town to find

Fremantle's Market Hall.

The Market Hall building was first Fremantle Town Hall at Kings Square: back through the town, we photographed Fremantle Town Hall at Kings Square, the civic and commercial heart of Fremantle; the Town Hall tower was decorated with the black swan emblem of Western Australia (see below left). Along Market Street we passed the ornate National Hotel, and withdrew a final cash from an ATM to conclude our time in Perth.

It was by now 4-45pm and our time in Fremantle was drawing to a close. Having confirmed

at the railway station that there were trains running back to Perth at

almost

After the brash modernity of Perth, Fremantle had made a refreshing day's relaxation for our final day in Australia. Unlike Port Adelaide, it had managed to preserve the heritage and charm of its dockland without this becoming over-twee and museum-ified, while at the same time keeping alive the port's commercial maritime trading traditions in the modern container terminal across the river. Overall it had been a thoroughly worthwhile and enjoyable concluding day to end our time in Australia. Return to Perth by train: back to the railway station, we managed to extract two tickets from the machines at the good-value price of $7-40, and boarded the waiting train back to Perth. During the 20 minute journey back through the suburbs of Perth, the sky quickly turned from attractively salmon-pink sunset to fully dark as the train pulled in to Perth station. We walked from the station's Northbridge exit over to the Brass Monkey pub for an early evening beer. Being Friday evening, most of the pub's bars were heaving with crowds of folk and throbbing with loud music, so again the sports bar was the only comparatively peaceful haven. We had intended to eat supper in the Asian Shanghai food hall along James Street, but still full from our hearty fish and chip lunch, we abandoned thoughts of supper and caught our final Blue and Red CAT buses back along towards the hostel. Fremantle had proved a very pleasant visit for our last day; weary from our long but satisfying final day in Oz, we sat in our room, having partly packed our kit ready for tomorrow's early departure. After eating our mini-supper of yoghurt along with the Persimmon fruit from Fremantle market, we turned in early.

Coming soon: tomorrow we

should begin the final phase of our round-the-world back-packing venture, this

time with a 2-day stop-over in the tropical heat of Singapore close to the

Equator, but all of this will be covered in the

next edition.

Next edition to be published quite soon

Published: 20 August 2021

|

BACK-PACKING TRIP TO AUSTRALIA 2011 - 2 day stop-over in Perth, Western Australia:

BACK-PACKING TRIP TO AUSTRALIA 2011 - 2 day stop-over in Perth, Western Australia: by some passengers, we need not have worried about the comparatively small amount we

were carrying. Rain had been pouring all morning, and the line of the Adelaide

Hills was totally obscured by rain-cloud. We eventually backed out for take-off

at gone noon, but the pilot reported a favourable tailwind that would help

enable us to catch up on lost time and reach Perth by 13-20. We put our watches

on to Perth time, meaning we took-off apparently at 10-50.

by some passengers, we need not have worried about the comparatively small amount we

were carrying. Rain had been pouring all morning, and the line of the Adelaide

Hills was totally obscured by rain-cloud. We eventually backed out for take-off

at gone noon, but the pilot reported a favourable tailwind that would help

enable us to catch up on lost time and reach Perth by 13-20. We put our watches

on to Perth time, meaning we took-off apparently at 10-50. Perth's Exclusive Back-packing Hostel:

we were welcomed at the Exclusive Back-packers Hostel in Adelaide Terrace by the warden, who gave

us an outline introduction to the city. Having settled our kit into our room, we set off to

spend our first afternoon in Perth, getting the lie of the land, finding our way

around the city, investigating public transport and sourcing information from

the Tourist Information Centre to plan our two days here. The first thing was to

find out more about Perth's public transport for our travel around the city. The

most important feature was Perth's Central Area Transit (CAT) free of charge

circular buses around the central area of the city; you can hop on and off as

often as you like (see Perth CAT Buses emblem right). The four CAT bus routes

around Central Perth are colour-coded routes Red, Green, Yellow and Blue (

Perth's Exclusive Back-packing Hostel:

we were welcomed at the Exclusive Back-packers Hostel in Adelaide Terrace by the warden, who gave

us an outline introduction to the city. Having settled our kit into our room, we set off to

spend our first afternoon in Perth, getting the lie of the land, finding our way

around the city, investigating public transport and sourcing information from

the Tourist Information Centre to plan our two days here. The first thing was to

find out more about Perth's public transport for our travel around the city. The

most important feature was Perth's Central Area Transit (CAT) free of charge

circular buses around the central area of the city; you can hop on and off as

often as you like (see Perth CAT Buses emblem right). The four CAT bus routes

around Central Perth are colour-coded routes Red, Green, Yellow and Blue ( Perth Museum displays on Stromatolites:

up on the Perth Museum's second floor, the Diamonds to Dinosaurs gallery traced the

origins of the Solar System, the formation of Earth's minerals, and evolution of

life on Earth. One of the most fascinating parts of the exhibition was about the

formation of Stromatolites (meaning layered rock),

rare and curious mineral structures found now at only two locations, one of

which is Hamelin Pool in the Shark Bay coastal area of Western Australia (

Perth Museum displays on Stromatolites:

up on the Perth Museum's second floor, the Diamonds to Dinosaurs gallery traced the

origins of the Solar System, the formation of Earth's minerals, and evolution of

life on Earth. One of the most fascinating parts of the exhibition was about the

formation of Stromatolites (meaning layered rock),

rare and curious mineral structures found now at only two locations, one of

which is Hamelin Pool in the Shark Bay coastal area of Western Australia ( of which we had previously known

little.

of which we had previously known

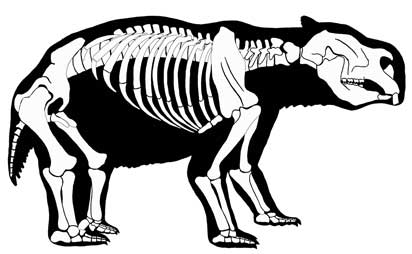

little. Perth Museum fossil displays on prehistoric Australian Megafauna: another section of the

vertebrates exhibition was devoted to an exhibition on Australian prehistoric

Megafauna. The display included the fossilised

bones of a Diprotodon (see left) and a caste of the complete skeleton of

this gigantic Wombat-like creature, the largest known

Marsupial the size of a rhinoceros and weighing up to 2 tons. Along with many other

members of the species group collectively known as the Australian megafauna,

it existed from about 1.6 million years ago until extinction some 46,000 years

ago. Diprotodon fossils have been found at sites across mainland Australia,

including complete skulls, partial skeletons, and foot impressions; they have been

depicted on Aboriginal rock art images, and female skeletons have been found with babies located

where the mother's pouch would have been. The museum displays also included the

mummified remains of the now extinct Thylacine, known colloquially as the

Tasmanian Tiger, one of the

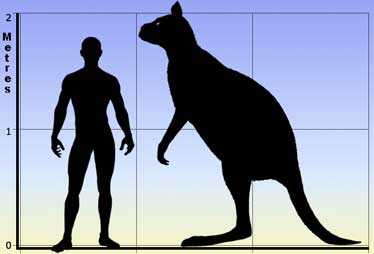

largest known carnivorous marsupials, and the fossilised skeleton of a gigantic prehistoric Kangaroo, the Procoptodon

(see right),

which stood over 2m tall and became extinct during the Pleistocene era. One panel

displayed a replica of the fossilised

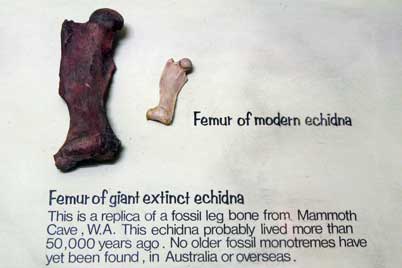

Perth Museum fossil displays on prehistoric Australian Megafauna: another section of the

vertebrates exhibition was devoted to an exhibition on Australian prehistoric

Megafauna. The display included the fossilised

bones of a Diprotodon (see left) and a caste of the complete skeleton of

this gigantic Wombat-like creature, the largest known

Marsupial the size of a rhinoceros and weighing up to 2 tons. Along with many other

members of the species group collectively known as the Australian megafauna,

it existed from about 1.6 million years ago until extinction some 46,000 years

ago. Diprotodon fossils have been found at sites across mainland Australia,

including complete skulls, partial skeletons, and foot impressions; they have been

depicted on Aboriginal rock art images, and female skeletons have been found with babies located

where the mother's pouch would have been. The museum displays also included the

mummified remains of the now extinct Thylacine, known colloquially as the

Tasmanian Tiger, one of the

largest known carnivorous marsupials, and the fossilised skeleton of a gigantic prehistoric Kangaroo, the Procoptodon

(see right),

which stood over 2m tall and became extinct during the Pleistocene era. One panel

displayed a replica of the fossilised

femur of an extinct giant Echidna found in

a WA cave, with alongside for comparison the femur of a present day Echidna (see

below left). This extinct animal lived more than 50,000 years ago, and is the oldest

known fossilised Monotreme ever found either in Australia or elsewhere.

femur of an extinct giant Echidna found in

a WA cave, with alongside for comparison the femur of a present day Echidna (see

below left). This extinct animal lived more than 50,000 years ago, and is the oldest

known fossilised Monotreme ever found either in Australia or elsewhere. Perth Museum displays on Monotremes:

we also learned much about the third group of mammals,

the egg-laying Monotremes (Echidnas and Platypuses). We had seen Echidnas in the

wild during our travels on Kangaroo Island and in captivity at Cleland Wildlife

Park, but despite our efforts in the rain at Flinders Chase, had not managed to see a Platypus

either. The

displays at Perth Museum included a taxidermied specimen of the Platypus along

with an Echidna, and a description of the curious features of these only surviving Monotremes.

Perth Museum displays on Monotremes:

we also learned much about the third group of mammals,

the egg-laying Monotremes (Echidnas and Platypuses). We had seen Echidnas in the

wild during our travels on Kangaroo Island and in captivity at Cleland Wildlife

Park, but despite our efforts in the rain at Flinders Chase, had not managed to see a Platypus

either. The

displays at Perth Museum included a taxidermied specimen of the Platypus along

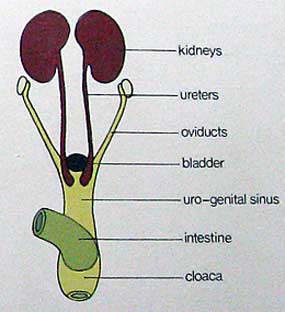

with an Echidna, and a description of the curious features of these only surviving Monotremes. difference which

distinguishes Monotremes from other Mammals also gives them their name:

Monotreme means one-orifice in Greek, referring to the single rear

bodily duct (the cloaca) for their urinary, defecatory, and reproductive

systems (see right). In addition, they are oviparous rather viviparous, but like

all mammals, female Monotremes nurse their young with milk from mammary glands.

Although classed as mammals principally because of milk-rearing their young,

Monotremes in many important respects such as egg-laying resemble reptiles, the

animal group from which the ancestors of all modern mammals and birds have

evolved. The common outlet of cloaca is a feature of birds and reptiles, whereas

all mammals other than Monotremes have two separate external outlets. Monotreme

skeletons also show many primitive characteristics reminiscent of reptiles:

their reptilian gait with legs side-spread and body low, results from the

archaic arrangement of shoulder girdle bones. The Monotreme shoulder girdle has

two bones which reptiles possess but which other mammals have lost (see left for

an Echidna skeleton displayed in Perth Museum). These primitive traits, sharing both mammalian and

reptilian characteristics, indicate that Monotremes diverged from the mammalian

line earlier than the Marsupials.

difference which

distinguishes Monotremes from other Mammals also gives them their name:

Monotreme means one-orifice in Greek, referring to the single rear

bodily duct (the cloaca) for their urinary, defecatory, and reproductive

systems (see right). In addition, they are oviparous rather viviparous, but like

all mammals, female Monotremes nurse their young with milk from mammary glands.

Although classed as mammals principally because of milk-rearing their young,

Monotremes in many important respects such as egg-laying resemble reptiles, the

animal group from which the ancestors of all modern mammals and birds have

evolved. The common outlet of cloaca is a feature of birds and reptiles, whereas

all mammals other than Monotremes have two separate external outlets. Monotreme

skeletons also show many primitive characteristics reminiscent of reptiles:

their reptilian gait with legs side-spread and body low, results from the

archaic arrangement of shoulder girdle bones. The Monotreme shoulder girdle has

two bones which reptiles possess but which other mammals have lost (see left for

an Echidna skeleton displayed in Perth Museum). These primitive traits, sharing both mammalian and

reptilian characteristics, indicate that Monotremes diverged from the mammalian

line earlier than the Marsupials. Echidnas: Echidnas, sometimes known as spiny ant-eaters, are the most abundant of

the Monotreme order of Mammals (see right). The four extant species of Echidnas together with

the Platypus are the only surviving members of the Monotreme order. They are the only living

Mammals that lay eggs, and are unique to Australia and New Guinea. Echidnas evolved

20~50 million years ago (see Evolutionary Chart above), and are descended from a now extinct

platypus-like Monotreme. This ancestor was aquatic, but Echidnas adapted to life on land.

Their diet consists of ants and termites, but they are only distantly

related to the true anteaters of South America. Superficially, they resemble

other spiny mammals such as hedgehogs and porcupines. Echidnas are medium-sized,

solitary mammals, dark brown in colour and covered with course hair and spines.

They have elongated, slender snouts and a small,

toothless mouth with long sticky tongue. Like the Platypus, their snout is

equipped with electro-sensors, and this sense is used to locate surrounding

objects. They have short, strong limbs with elongated claws, curved backwards on

their hind limbs, making them powerful diggers. They feed by tearing open soft

logs and anthills, using the long, sticky, swiftly-darting tongue to scoop up prey. When

alarmed, they roll up into a prickly ball as we witnessed on Kangaroo Island

(

Echidnas: Echidnas, sometimes known as spiny ant-eaters, are the most abundant of

the Monotreme order of Mammals (see right). The four extant species of Echidnas together with

the Platypus are the only surviving members of the Monotreme order. They are the only living

Mammals that lay eggs, and are unique to Australia and New Guinea. Echidnas evolved

20~50 million years ago (see Evolutionary Chart above), and are descended from a now extinct

platypus-like Monotreme. This ancestor was aquatic, but Echidnas adapted to life on land.

Their diet consists of ants and termites, but they are only distantly

related to the true anteaters of South America. Superficially, they resemble

other spiny mammals such as hedgehogs and porcupines. Echidnas are medium-sized,

solitary mammals, dark brown in colour and covered with course hair and spines.

They have elongated, slender snouts and a small,

toothless mouth with long sticky tongue. Like the Platypus, their snout is

equipped with electro-sensors, and this sense is used to locate surrounding

objects. They have short, strong limbs with elongated claws, curved backwards on

their hind limbs, making them powerful diggers. They feed by tearing open soft

logs and anthills, using the long, sticky, swiftly-darting tongue to scoop up prey. When

alarmed, they roll up into a prickly ball as we witnessed on Kangaroo Island

( Platypus:

the Platypus, sometimes called Duck-billed, is a carnivorous, semi-aquatic, egg-laying

Mammal, endemic to Eastern Australia and Tasmania, and inhabiting streams and rivers; it

is extinct in South Australia apart from a reintroduced population on Kangaroo

Island. There is only one species of Platypus, but a number of ancestral species

occur in the fossil record, such as the large platypus-like Obdurodon. Its

streamlined body, webbed feet, and broad, flat, beaver-like tail are highly

specialised for swimming (see left); the body and tail are covered with waterproofed,

dense, brown insulated fur with a texture similar to moles, and the elongated

snout is covered in soft skin to form the bill (see below right). Like the Echidna, the Platypus'

side-spreading legs (rather than underneath like other mammals) give it a

reptilian gait (see below left for Platypus

Platypus:

the Platypus, sometimes called Duck-billed, is a carnivorous, semi-aquatic, egg-laying

Mammal, endemic to Eastern Australia and Tasmania, and inhabiting streams and rivers; it

is extinct in South Australia apart from a reintroduced population on Kangaroo

Island. There is only one species of Platypus, but a number of ancestral species

occur in the fossil record, such as the large platypus-like Obdurodon. Its

streamlined body, webbed feet, and broad, flat, beaver-like tail are highly

specialised for swimming (see left); the body and tail are covered with waterproofed,

dense, brown insulated fur with a texture similar to moles, and the elongated

snout is covered in soft skin to form the bill (see below right). Like the Echidna, the Platypus'

side-spreading legs (rather than underneath like other mammals) give it a

reptilian gait (see below left for Platypus skeleton). The Platypus is an excellent

swimmer and spends much of its time in water foraging for food. Like other

Monotremes, the Platypus senses its prey by means of 40,000 electro-receptors in

its bill, which detect electric fields generated by its prey's muscular

contraction; this explains the characteristic side-to-side motion of its head

while hunting. The Platypus closes its eyes, ears and nose underwater, and feeds

not by sight or smell, but hunts by electro-location; this additional sense

probably evolved to allow the animal to forage nocturnally in murky waters.

Monotremes are the only mammals with this electro-sensory ability apart from one

species of dolphin. Platypus are voracious feeders, using their sensitive bills

to probe muddy riverbeds for worms, larvae, shrimps and crustaceans. It needs to

eat some 20% of its own body weight each day, which requires it to spend

typically 12 hours daily feeding and storing prey in cheek pouches. It uses its

tail for storing fat reserves in times of food shortage, an adaptation also

found in animals like the Tasmanian Devil. Although being warm-blooded, the

skeleton). The Platypus is an excellent

swimmer and spends much of its time in water foraging for food. Like other

Monotremes, the Platypus senses its prey by means of 40,000 electro-receptors in

its bill, which detect electric fields generated by its prey's muscular

contraction; this explains the characteristic side-to-side motion of its head

while hunting. The Platypus closes its eyes, ears and nose underwater, and feeds

not by sight or smell, but hunts by electro-location; this additional sense

probably evolved to allow the animal to forage nocturnally in murky waters.

Monotremes are the only mammals with this electro-sensory ability apart from one

species of dolphin. Platypus are voracious feeders, using their sensitive bills

to probe muddy riverbeds for worms, larvae, shrimps and crustaceans. It needs to

eat some 20% of its own body weight each day, which requires it to spend

typically 12 hours daily feeding and storing prey in cheek pouches. It uses its

tail for storing fat reserves in times of food shortage, an adaptation also

found in animals like the Tasmanian Devil. Although being warm-blooded, the

Platypus has an average body temperature of 32°C compared with the 37° typical

of Placental Mammals. Adult Platypus chew with horny plates which replace the

small, irregular teeth of the young. It is one of the few venomous mammal

species: the male platypus has a spur on its hind ankles that delivers defensive

venom; although powerful enough to kill small-sized animals, the venom is not

fatal to humans but does cause excruciating pain. Outside the mating period,

Platypus are solitary, living in a simple ground burrow. After mating, the

female constructs a deeper, more elaborate nursery burrow typically in river

banks, insulating this as a nest with dead leaves and sealing herself inside;

the male takes no further part in rearing the young. Usually 2 eggs are produced

and develop in utero for 28 days. After laying, the mother keeps the eggs

warm by holding them between her body and tail. During this 10 day incubation,

the undeveloped embryos are initially nourished by the yolk sac, until finally

tearing open the leathery eggs with their egg-tooth. The tiny, newly hatched

young are blind, hairless and helpless, and are suckled with milk secreted from

mammary glands in the mother's abdomen. After 3~4 months, the young emerge from

the burrow to become independent.

Platypus has an average body temperature of 32°C compared with the 37° typical

of Placental Mammals. Adult Platypus chew with horny plates which replace the

small, irregular teeth of the young. It is one of the few venomous mammal

species: the male platypus has a spur on its hind ankles that delivers defensive

venom; although powerful enough to kill small-sized animals, the venom is not

fatal to humans but does cause excruciating pain. Outside the mating period,

Platypus are solitary, living in a simple ground burrow. After mating, the

female constructs a deeper, more elaborate nursery burrow typically in river

banks, insulating this as a nest with dead leaves and sealing herself inside;

the male takes no further part in rearing the young. Usually 2 eggs are produced

and develop in utero for 28 days. After laying, the mother keeps the eggs

warm by holding them between her body and tail. During this 10 day incubation,

the undeveloped embryos are initially nourished by the yolk sac, until finally

tearing open the leathery eggs with their egg-tooth. The tiny, newly hatched

young are blind, hairless and helpless, and are suckled with milk secreted from

mammary glands in the mother's abdomen. After 3~4 months, the young emerge from

the burrow to become independent. This had been a highly productive time spent in the Perth Museum and we had

gained so much new understanding, particularly about the uniquely Australian

Marsupials and Monotremes; the Museum had been a mixture of old-fashioned displays and

modern interactive and informative presentations, but all in all it had been

time well spent in terms of learning. It

has to be said that we were fascinated at the one extreme by what we had learned

about Stromatolites and Monotremes, and truly appalled

and distressed at the other end of the spectrum by all

This had been a highly productive time spent in the Perth Museum and we had

gained so much new understanding, particularly about the uniquely Australian

Marsupials and Monotremes; the Museum had been a mixture of old-fashioned displays and

modern interactive and informative presentations, but all in all it had been

time well spent in terms of learning. It

has to be said that we were fascinated at the one extreme by what we had learned

about Stromatolites and Monotremes, and truly appalled

and distressed at the other end of the spectrum by all

the horrific background

understanding about the Stolen Generations issue. Leaving the museum, we

crossed the upper pedestrianised part of James Street in the Northbridge

district in search of a quick lunch at an Asian food hall.

the horrific background

understanding about the Stolen Generations issue. Leaving the museum, we

crossed the upper pedestrianised part of James Street in the Northbridge

district in search of a quick lunch at an Asian food hall. Western Australia war memorial:

across the beautifully maintained lawns, we stood looking out from the viewing

look-out behind the war memorial across to the magnificent panorama of the wide

Swan River (

Western Australia war memorial:

across the beautifully maintained lawns, we stood looking out from the viewing

look-out behind the war memorial across to the magnificent panorama of the wide

Swan River ( which linked the north and south shores of the

Swan River

(

which linked the north and south shores of the

Swan River

( recorded that allegedly it had been kindled in

2001 by the Queen; in fact, we had been told at the Visitor Centre, it had failed to light at the

official ceremony and had been lit later by a council workman!

recorded that allegedly it had been kindled in

2001 by the Queen; in fact, we had been told at the Visitor Centre, it had failed to light at the

official ceremony and had been lit later by a council workman! Perth Botanic Gardens at King's Park: we headed across the parkland to

Perth Botanic Gardens at King's Park: we headed across the parkland to  did

see Crimson Rosellas and Australian Ringnecks feeding tamely on the

lawns. Ringnecks are a gregarious Parrot species (see right) (

did

see Crimson Rosellas and Australian Ringnecks feeding tamely on the

lawns. Ringnecks are a gregarious Parrot species (see right) ( are

locally displaced by Rainbow Lorikeets, an introduced species which aggressively

competes for nesting space.

are

locally displaced by Rainbow Lorikeets, an introduced species which aggressively

competes for nesting space. nectar-eating animals, including birds, bats, rats,

possums, bees and invertebrates. The nectar of Banksia has also been used by

Indigenous people, who either eat it straight from the flowers or soak it in

water to make a sweet drink. Although they can grow in a wide range of Australian

environments, and are adapted to withstand bush-fires, many Banksia species are now threatened due to excessive land

clearing, burning, and disease.

nectar-eating animals, including birds, bats, rats,

possums, bees and invertebrates. The nectar of Banksia has also been used by

Indigenous people, who either eat it straight from the flowers or soak it in

water to make a sweet drink. Although they can grow in a wide range of Australian

environments, and are adapted to withstand bush-fires, many Banksia species are now threatened due to excessive land

clearing, burning, and disease.  in the Botanic Gardens, we found another curiously shaped flowering shrub

native to Western Australia, the Granite Bottlebrush (Melaleuca ellipica)

(see below left) (

in the Botanic Gardens, we found another curiously shaped flowering shrub

native to Western Australia, the Granite Bottlebrush (Melaleuca ellipica)

(see below left) ( which opens to

release the seed. Again Eucalyptus flowers produce abundant nectar, providing

food for insects, birds, bats and possums, which act as pollinators. At the

Botanic Gardens, we photographed the Silver Princess Eucalyptus variety (Eucalyptus

caesia) (see right) (

which opens to

release the seed. Again Eucalyptus flowers produce abundant nectar, providing

food for insects, birds, bats and possums, which act as pollinators. At the

Botanic Gardens, we photographed the Silver Princess Eucalyptus variety (Eucalyptus

caesia) (see right) ( earlier. The pub brewed its own heavy stout, a delicious 6% ABV beer and the closest you could get to

true Dublin Guinness in the southern hemisphere. Even at 6-00pm

the pub bars were throbbing with loud 'music' and we were forced to seek

sanctuary in the comparatively peaceful environment of the sport bar!

earlier. The pub brewed its own heavy stout, a delicious 6% ABV beer and the closest you could get to

true Dublin Guinness in the southern hemisphere. Even at 6-00pm

the pub bars were throbbing with loud 'music' and we were forced to seek

sanctuary in the comparatively peaceful environment of the sport bar! which she lit for us. From the menu we each ordered rib-eye steak which

we were told was served with vegetables; just to give a familiar feel, we also

ordered some rice, which came in the usual solidified mass. Five small pieces of

tasty-looking rib-eye steak were brought to our table, along with little dishes

of various unknown vegetable matter. But this was truly novel Asiatic dining: we

had no plates or dishes, and the only cutlery was of course chop sticks and a

pair of kitchen scissors. Well, seasoned international travellers we may be, but

eating steak with no plates and nothing more than kitchen scissors and chop

sticks, especially when hungry and ultra-weary, defied imagination. Sacrificing

pride in the interests of satisfying hunger, we requested dishes, knives and

forks. The meat was barbecued and the vegetables sampled; thankful for the

civilised luxuries of dishes to eat from, and knives and forks to eat with, we

enjoyed our oriental supper.

which she lit for us. From the menu we each ordered rib-eye steak which

we were told was served with vegetables; just to give a familiar feel, we also

ordered some rice, which came in the usual solidified mass. Five small pieces of

tasty-looking rib-eye steak were brought to our table, along with little dishes

of various unknown vegetable matter. But this was truly novel Asiatic dining: we

had no plates or dishes, and the only cutlery was of course chop sticks and a

pair of kitchen scissors. Well, seasoned international travellers we may be, but

eating steak with no plates and nothing more than kitchen scissors and chop

sticks, especially when hungry and ultra-weary, defied imagination. Sacrificing

pride in the interests of satisfying hunger, we requested dishes, knives and

forks. The meat was barbecued and the vegetables sampled; thankful for the

civilised luxuries of dishes to eat from, and knives and forks to eat with, we

enjoyed our oriental supper. Having raided the Kazakhstani supermarket opposite the hostel for breakfast foodstuffs,

we returning to our accommodation. Relieved of the rowdy shouting of alleged prayers from the previous young oriental

neighbours, we settled in for a soundly peaceful night's sleep. We had

managed to pack into today a satisfyingly large number of visits, and had

learned much in such a brief time about Western Australia, its economy, geology, fauna and flora.

We looked forward to our trip tomorrow down the Swan River to spend the day at

Perth's port of Fremantle.

Having raided the Kazakhstani supermarket opposite the hostel for breakfast foodstuffs,

we returning to our accommodation. Relieved of the rowdy shouting of alleged prayers from the previous young oriental

neighbours, we settled in for a soundly peaceful night's sleep. We had

managed to pack into today a satisfyingly large number of visits, and had

learned much in such a brief time about Western Australia, its economy, geology, fauna and flora.

We looked forward to our trip tomorrow down the Swan River to spend the day at

Perth's port of Fremantle. Cruise down the Swan River to Fremantle:

we woke to another clear sky and hot, sunny morning. Our plan for today, our final full day

in Australia, was to take the river-cruise from the city jetties down the Swan

River, and to spend the day down at Perth's port of Fremantle at the mouth of

the Swan River on the Indian Ocean. After breakfast, we walked along to the bus

stop at 8‑30am intending to catch the #37 bus along to the Swan River ferry

terminal. At the bus stop however two local ladies not only insisted on helping

us, but also stipulated in no uncertain terms that we should walk along to the

pier through the river-side park rather than catch the bus. Unable to contest such insistent exhortations,

we duly descended to the riverside Langley Park and, admitting

that the unrelenting ladies were right, followed the delightful road through the

parkland along to the ferry piers (see

Cruise down the Swan River to Fremantle:

we woke to another clear sky and hot, sunny morning. Our plan for today, our final full day

in Australia, was to take the river-cruise from the city jetties down the Swan

River, and to spend the day down at Perth's port of Fremantle at the mouth of

the Swan River on the Indian Ocean. After breakfast, we walked along to the bus

stop at 8‑30am intending to catch the #37 bus along to the Swan River ferry

terminal. At the bus stop however two local ladies not only insisted on helping

us, but also stipulated in no uncertain terms that we should walk along to the

pier through the river-side park rather than catch the bus. Unable to contest such insistent exhortations,

we duly descended to the riverside Langley Park and, admitting

that the unrelenting ladies were right, followed the delightful road through the

parkland along to the ferry piers (see

above right). The morning sun was magnificent and lighting

perfect, and we revelled in the many photographic

opportunities for views of Perth city skyscrapers

(

above right). The morning sun was magnificent and lighting

perfect, and we revelled in the many photographic

opportunities for views of Perth city skyscrapers

( the

right hand side for photographs of the city from the river, and sat back to enjoy the cruise down river.

the

right hand side for photographs of the city from the river, and sat back to enjoy the cruise down river. Anzac cliffs and the WA

War Memorial standing prominently on a bluff up at King's Park where we had

walked yesterday afternoon. Beyond the Narrows Bridge, which carried the

Expressway and railway across the width of the river (

Anzac cliffs and the WA

War Memorial standing prominently on a bluff up at King's Park where we had

walked yesterday afternoon. Beyond the Narrows Bridge, which carried the

Expressway and railway across the width of the river ( swung

across the width of the river, passing several so-called Royal Yacht Clubs, all

established at dubiously dated 19th century landmarks, with now not a yacht in

sight. All were now filled with ultra-pretentious, luxury motor vessels belonging to

Perth's idle nouveaux-riches (see right). The ferry continued down-river,

passing the extravagantly ostentatious, multi-million $$$s river-houses of Perth citizens who had made their mega-buck fortunes digging up

Western Australia's mineral resources. The commentary pointed out delightful

natural bays enclosed by sand-bars as we continued down-river. After a

delightful hour's cruise

along the lower river,

the ferry passed under the bridges of Fremantle, alongside the container ships,

and moored at the

swung

across the width of the river, passing several so-called Royal Yacht Clubs, all

established at dubiously dated 19th century landmarks, with now not a yacht in

sight. All were now filled with ultra-pretentious, luxury motor vessels belonging to

Perth's idle nouveaux-riches (see right). The ferry continued down-river,

passing the extravagantly ostentatious, multi-million $$$s river-houses of Perth citizens who had made their mega-buck fortunes digging up

Western Australia's mineral resources. The commentary pointed out delightful

natural bays enclosed by sand-bars as we continued down-river. After a

delightful hour's cruise

along the lower river,